Anneli Xie

Profs. Pat Berman & Alice Friedman

ARTH 322: The Bauhaus

2019/03/20

Profs. Pat Berman & Alice Friedman

ARTH 322: The Bauhaus

2019/03/20

Small Worlds and Big Ideas: Concerning the Spiritual in Kandinsky’s Kleine Welten IV

Fig 1. Wassily, Kandinsky. Kleine Welten IV, 1922. Lithograph. 33.6 x 28.9 cm. Boston,

Museum of Fine Arts. https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/kleine-welten-iv-166700.

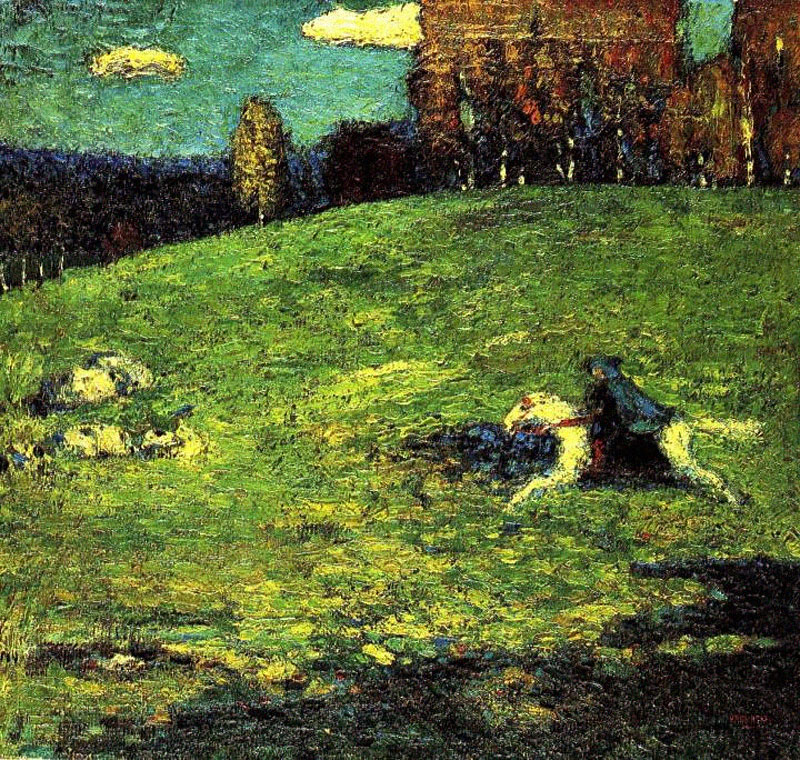

Although being showcased as only a part of Wassily Kandinsky’s 12 works portfolio Kleine Welten (Small Worlds), Kleine Welten IV (fig. 1) is an alluring work that stands out on its own. Framed on a 34.3 x 28 cm passe-partout, Kleine Welten IV, together with the rest of the works in the portfolio, occupy an entire wall in the dimmed-lit exhibition hall at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston as part of the show “Radical Geometries: Bauhaus Prints, 1919-33.” Exhibited in chronological order, Kleine Welten IV is positioned in the upper right corner of the wall and depicts, much like the name reveals, a small world. Not only working on a self-contained level, however, Kleine Welten IV also reveals a utopian vision of a harmonious reality when related to the other works of the portfolio. Created within six months of Kandinsky’s teachership at the Bauhaus in Weimar, where he was appointed head of the mural workshop in 1922, (Poling 1983, 41) the 12 prints that make up Kleine Welten (Small Worlds) are all significant pieces in Kandinsky’s career as they combine figurative representation, more common in Kandinsky’s impressionist past (see fig. 2), with the complex geometric abstractions that later became his trademark. (Guerman 1997, 10) Although Kandinsky’s move towards abstraction started already in the 1910s, with an added momentum from his theories on non-figurative art and his 1911 publication “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” Kandinsky produced prior and after Kleine Welten (Small Worlds) are significantly different. Kleine Welten (Small Worlds) and Kandinsky’s appointment at the Bauhaus can thus be seen as a turning, – or maybe rather a self-realization – point for the rest of Kandinsky’s career, after which Kandinsky’s concerns with the spiritual were much more heavily reflected in his art, as can be seen in his theories on color, form, and his turn towards the geometric and the abstract. As part of this chronicle, Kleine Welten IV, the fourth in the portfolio series, is a good representation of Kandinsky’s attempt in doing so, making use of the relationship between color, forms, and composition to translate his works of art into a spiritual domain.

Wassily, Kandinsky. Der Blaue Reiter, 1903. Oil on Cardboard. 55.0 × 65.0 cm. Zurich, Private Collection.

Accessed March 15, 2019. https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-81.php.

Accessed March 15, 2019. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80496.

Fig. 4. Kandinsky, Wassily. “Circles on Black,” 1921. Oil on Canvas, 136.5 x 120 cm. (The Solomon R.

Guggenheim Museum, New York).

In Kandinsky, Russian and Bauhaus years by Clark V. Poling. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1983. p.118, fig. 42.

In Kandinsky, Russian and Bauhaus years by Clark V. Poling. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1983. p.118, fig. 42.

Fig. 5. Kandinsky, Wassily. “Composition #224 (On White) ” 1920. Oil on Canvas, 95.0 × 138.0 cm. St. Petersburg, The Russian Museum.

Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-548.php.

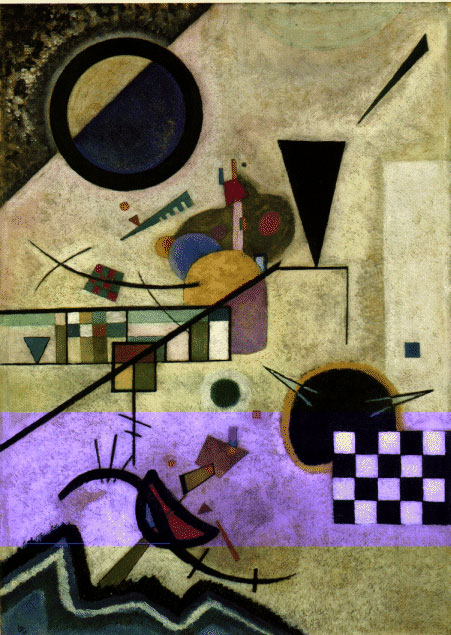

Kleine Welten IV is the fourth of Kandinsky’s portfolio and a good

representation of the blend of styles, conflicts, and ideologies discussed

above. The work – a lithograph in violet, green, yellow, and black, printed on

white wove paper – presents a microcosm of lines, shapes, points, and colors,

slowly revealing the presence of recognizable objects – a process described by

Rose Carol Washton Long as the “veiling of [images.]” (Washton Long 1975, 227)

Similar to the planetary

composition of Kandinsky’s 1921 work Circles

on Black (fig. 4), Kleine Welten IV appears

from the thick black outline of a circle, starting in the left corner and

stretching across two-thirds of the vertical page. From this circle, several

undistinguishable forms, lines, and shapes – but also recognizable motifs and

associations, such as what appears to be a representation of a boat propellor,

ship funnel, and waves of water, as well as a patch of grass and a black

and white checkerboard – emerge. The cosmic compositions of Kleine Welten IV and its references to

water and nature can be connected to the utopian planning ideas of satellite

cities and the garden city movement (with its anarchist ideals), possibly introduced to Kandinsky by the theories of Russian writer and

anarchist Peter Kropotkin, who believed humans were happiest in small

communities and who sought to restructure society in such a way. (Koehler 1998, 432)

As

someone describing himself as “anarchistic,” there is no doubt that Kandinsky

was familiar with Kropotkin’s writing, even referring to him in a

correspondence with Serbian writer Dimitri Mitrinovic. (Koehler 1998, 439)

Kropotkin’s emphasis on the

collective and cooperative effort was

later adopted by Walter Gropius and put into play at the birth of the Bauhaus. (Poling 1983, 42)

It

will thus be suggested that Kandinsky, surrounded by these utopian ideals both

before and after his move from Russia to Germany in 1922, derived ideas from

both Kropotkin and Gropius to influence his creation of Kleine Welten (Small Worlds). As for the checkerboard, it was a

recurring element in Kandinsky’s works, first used in his 1920 Composition #224 (On White) (fig. 5) and

frequently seen during his early Bauhaus years – not only in Kleine Welten IV, but also in later

works such as Orange (fig. 6) from

1923 and Contrasting Sounds (fig. 7)

from 1924. Whereas the use of the checkerboard was drawn from the Russian

constructivist movement, whose first chairman was Kandinsky, (Giovannini 1990) it

also aligned with the forms of the Bauhaus and was frequently employed “as

devices for designs and formats for student exercises” (Poling 1983, 38) – an indicator of how both

Kandinsky’s Russian heritage, as well as his teachership and students at the

Bauhaus continued to influence his work. Combining the recognizable features of

the built environment in play with the unrecognizable forms of the rest of the

plate in a cosmic composition, conveying the utopian ideals of Kropotkin and

Gropius, Kleine Welten IV suggests a

hovering conflict between the realistic and the ideal. Furthermore, the

majority of objects protrude from the circle, sometimes covering both the

outline of the circle, as well as objects crossing its path – such as a

black diagonal line cutting across the circle, left to right, at an

approximately 25 degree angle – conveying a sense of depth in a flattened

perspective. The clashing of objects adds an element of conflict by challenging

the centripetal force of the enclosed circle with the centrifugal forces of the

protruding objects, perhaps hinting at an equilibrium of power in play; the

spiritual and the earthly in harmony.Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-548.php.

Fig. 6. Kandinsky, Wassily. “Orange,” 1923. Lithograph, 48 x 44.2 cm. New York, Museum of Modern Art.

Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/70099.

Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/70099.

Fig. 7. Kandinsky, Wassily. “Contrasting Sounds,” 1923. Oil on Cardboard, 70.0 × 49.5 cm. Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou.

Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-237.php.

For Kandinsky, the

relationship between color, form, and humanity was the most important. (Kandinsky 2008, 59) In

his 1911 publication “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” he extensively mentions

the human connection to color, stating that colors “produce a spiritual

vibration” to the sensitive human soul. Regarding the palette of Kleine Welten IV, Kandinsky asserts that

“orange is like a man, convinced of its own powers, [...] violet a cooled red,

[...] rather sad and ailing” and

green is “the most restful color that exists.” About the two monochrome

colors, black and white, Kandinsky writes poetically: “[White] is not a dead

silence, but one pregnant with possibilities. [...] A totally dead silence, on

the other hand, a silence with no possibilities, has the inner harmony of black.” Kandinsky’s relationship to form was similarly spiritual, with a belief that an

artist’s goal should not be mastery of form, “but rather the adapting of form

to its inner meaning,” and

that “each form which goes to make up a composition has a simple inner value,

which has in its turn a melody;” (Kandinsky 2008, 84-89) a

circle deemed to be the most stable yet unstable form (Kandinsky 1979, 81) and a symbol of eternity. According to Susan J. Soriente, the circle is also “an important symbol in many

cultures, often representing [...] the unity of opposites into oneness,” (Soriente 2010, 4) which relates back to Kleine Welten IV’s

opposing yet balanced centripetal and centrifugal forces. The black diagonal

line cutting through the circle, on the other hand, has “a greater inner

tension [than vertical and horizontal lines],” (Kandinsky 1979, 65) and further emphasizes the

dynamic tension present between the two. With Kandinsky’s thoughts on form and

color in mind, it can be derived that Kandinsky “created mysterious shapes and

provided lucid explanation behind their working to inculcate through his shapes

the ultimate good of spirituality,” as Syed Gowhar Andrabi

suggests in his essay “Concerning the Spiritual in Kandinsky’s Shapes;” and

that Kandinsky’s use of geometric circles, especially in contrast with his more

melodious organic forms and the vivid dynamism of his diagonal lines, are

suggestive of a harmony between an earthly chaos and an idealized spiritual

domain.Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.wassilykandinsky.net/work-237.php.

Kleine Welten IV and its interplay in Kleine Welten is a significant example of Kandinsky’s application of his theories on spirituality and art. Inspired by utopian visions of both the Bolshevik Russia that Kandinsky left and the community at the Bauhaus which he entered, Kleine Welten IV showcases both Kandinsky’s emerging abstract geometric style, as well as his versatility and mastery of different techniques, colors, and compositions. As a composite collection, too, Kleine Welten (Small Worlds) addresses the self-contained singular work and its participation in a compound, displaying a harmony between the singular and the collective; and even though many of the portfolio plates seem to oppose and contradict each other, they all form a harmonious whole. This balance, of earthly chaos and spiritual divine, can be seen as an attempt to translate art into a spiritual dimension for his audience; and to Kandinsky, this is what art was all about – transcending the souls of peoples by combining the language of color and line as a spiritual teacher of the world. With a belief of each form having a color and a melody of its own, Kandinsky viewed himself as an artist merely replying to these, acting as “the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” (Kandinsky 2008, 62) As those to whom his art has spoken, we bear his testimony.

References

Andrabi, Syed G. “Concerning the Spiritual in Kandinsky’s Shapes.” 2013. https://www.academia.edu/6472706/Concerning_the_spiritual_in_Kandinskys_shapes.

Giovannini, Joseph. “Modern Long Ago: The Comeback of Russian Constructivism.” New York Times, December 30, 1990. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/12/30/books/modern-long-ago-the-comeback-of-russian-constructivism.html.

Guerman, Mikhaïl. Wassily Kandinsky. New York: Parkstone Press, 1997.

Kandinsky, Wassily. “Circles on Black,” 1921. Oil on Canvas. 136.5 x 120 cm. (Collection The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY). In Kandinsky, Russian and Bauhaus years by Clark V. Poling. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1983, p. 118

Kandinsky, Wassily. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Translated by Michael T. H. Sadler. Auckland: The Floating Press, 2008.

Kandinsky, Wassily. Point to Line to Plane. Translated by Howard Dearstyne and Hilla Rebay. New York: Dover Publications, 1979.

Koehler, Karen. “Kandinsky’s Kleine Welten and Utopian City Plans.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 57, no. 4. (December 1998): 432-47.

Long, Rose-Carol W. “Kandinsky's Abstract Style: The Veiling of Apocalyptic Folk Imagery.” Art Journal 34, no. 3 (Spring 1975): 217-27.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Museum label for Wassily Kandinsky, Kleine Welten (Small Worlds). Boston, MA, February 24, 2019.

Poling, Clark V. Kandinsky: Russian and Bauhaus Years. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1983.

Soriente, Susan J. “Divine Abstractions: Spiritual Expressions in Art.” Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications, 25 (2010): 1-13.