Anneli Xie

Profs. Pat Berman & Alice Friedman

ARTH 322: The Bauhaus

2019/05/21

Profs. Pat Berman & Alice Friedman

ARTH 322: The Bauhaus

2019/05/21

SWEDISH DESIGN: FROM MODEST NOVELTY TO GLOBAL PHENOMENON

The influences of the Bauhaus on the export of Swedishness

The influences of the Bauhaus on the export of Swedishness

In the boom and bust of the 19th century industrial revolution, the

origins of the Bauhaus lie in anxieties of the soullessness of modern

manufacturing, the fear of art’s loss of social relevance, and a wish to

reunite creativity and manufacturing. In the Bauhaus manifesto released in 1919,

the founder of the school, Walter Gropius, stated that “there is no essential

difference between the artist and the craftsman” and urged to “create a new

guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant

barrier between craftsman and artist.” (Wingler 1969, 31-33) With an initial vision of returning to the crafts inspired by the guilds in

Medieval times, the Bauhaus soon, however, shifted its gears to the ideas of

industry and mass production. (Lupton and Miller 1993, 38-45) In

1923, Walter Gropius re-stated the aims of the Bauhaus by declaring a slogan of

“art and technology – a new unity.” (Schuldenfrei 2018, 152) Up

until 1928, under Gropius’ lead, design was viewed as “neither an intellectual

nor a material affair, but simply an integral part of the stuff of life,

necessary for everyone in a civilized society.” (Buchanan 1992, 6) As a result, Bauhaus started prioritizing the industrial materials of steel and

glass, simple and geometric forms, and an aesthetic valuing function over

ornamentation. Spearheading a new movement aiming to fuse art and technology,

the works produced during this time, however, remained expensive in their day

and were only available to a select group of people. In 1928, when Gropius

stepped down to the new director of the school, Hannes Meyer, even Meyer was

dismayed at what the Bauhaus had become. Representing an argument that the

school had diverged from one of its initial goals, making design available to

the people, Meyer declared a new slogan of “people’s needs instead of luxury

needs!” (Schuldenfrei 2018, 152) Today, 100 years after the Bauhaus opening in 1919, the school has inspired and

paved way for much of the industrial design that surrounds us, mass produced in

factories and sold in batch all over the world; but during Bauhaus’ short-lived

existence, forced by the Nazis to close in 1933, not many products actually

made it into the factory and out to the general public. Instead, this vision became reality elsewhere.

Fig. 1. The cover of the 2019 IKEA Catalog. IKEA. ”Pressbilder IKEA katalogen våren 2019.”

Digital image. IKEA. Accessed May 5, 2019. https://press.ikea.se/katalogen_varen2019/.

One of the greatest examples of the realization of Bauhaus’ goals and aspirations can be found in the region of Scandinavia. In the past decade, Scandinavia has overflown with praise from countries all over the world. Labeled by British author Michael Booth as a “nearly perfect people,” (Booth 2014, 1) the Scandinavians have continuously topped the World Chart indexes in happiness and equality. (Helliwell, Layard and Sachs 2019) As “the Nordic Model” has become a common topic of discussion; and as a dozen of books focusing on the Scandinavian concepts such as the Finnish sauna, the Swedish “lagom,” and the Danish and Norwegian “hygge” have been published, Scandinavia has taken the world by storm.

In the design world, Scandinavia has long had a seat at the table, with Sweden at the forefront, strongly influencing the increasing popularity of Scandinavian design. Although a nation of only 10 million inhabitants, Sweden has managed to have a far-stretched global outreach within the field of design by alluding to its founding principles of design work and the success of its biggest design company, the home-furnishing IKEA. (Dagens Industri 2018) With Sweden at the forefront, the concept of Scandinavian Design has become so notable that it has claimed its own name: The New Nordic. Influenced by the nature of the Bauhaus, seeking to combine function and form in a simple and minimalist way, The New Nordic also encompasses an added layer of hygge that has traditionally been very important in Scandinavian homes. (Gundtoft 2015, 10-11) With everything in moderation, these two opposing strands come together to encompass both the Swedish vision of lagom, while simultaneously giving Sweden an international superstar status within the design world. Yet, despite the chic and state-of-the-art Swedish identity that has been advertised globally over the past few years, Swedish design has remained unobtrusive and modest, permeating society in an intuitive and almost unnoticeable way. Continuously striving for egalitarianism, Swedish design has chosen to remain humble rather than to elevate status and build hierarchies; similarly to the Bauhaus focusing rather on “people’s needs rather than luxury needs.” Everything that is accessible to one person should also be available to the other – no matter their social differences. In the Swedish stuff of life, everything has acquired a certain political vitality in its quiet promotion of social democracy. Behind the exported ideas of hygge, lagom, and Swedish superstar companies such as IKEA and H&M, lies an entire nation to be explored and discovered; one of humility and reticence.

When exploring Sweden’s design history, the concept of Swedishness takes root in a synthesis of social democracy, design movements, and creative pioneers. This paper will argue that Sweden grew from a modest novelty into a global phenomenon by realizing Bauhaus’ goal of making design available to the masses, and that the functionalist influences that Bauhaus brought to Sweden were essential in completing this quest. In conceptualizing Swedish design, the convergence of the Bauhaus with national ideals and politics has been crucial; and without it, the export of Swedishness might have never succeeded.

Fig. 2. Alberget 4B, Stockholm, in 1890, an upper-class dwelling in neo-renaissance style.

Orling, B. Alberget 4B, interiör i Rydbergska stiftelsens hus. Digitala stadsmuseet.

Accessed May 3, 2019. http://digitalastadsmuseet.stockholm.se

The birth of Swedish design can be traced back to the 1800s, with the first ever international showcase of Swedish design taking place at the Great Exhibition of London in 1856. The Great Exhibition was the first ever world fair, hosting over six million visitors during its six month showcase. Sweden’s participation in the expo was meager, dominated by different samples of wood and steel. Unnoticed by the rest of the world at the time, it would take another 50 years for Sweden to fully re-enter into the international playing field of design – largely because of the advancement of industrialism. (Brunnström 2010, 21-24)

With the first Swedish woodwork factory built during the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851, it wasn’t until the latter part of the 1800s that industrialization really prospered. During this time, Sweden was, despite its current egalitarian status, highly unequal; and the Swedish elite sought outwards in satisfying their taste for design. (Kristoffersson 2015, 76) Dominated by the neo-renaissance and neo-rococo influences of the rest of Europe, it was not uncommon for the upper classes to house interior designs inspired by the French rococo with porcelain imported from the Dutch East Indies on display. (Brunnström 2010, 55) As one might imagine, Swedish design in the 1800s was almost opposite to its common perception today. Instead of the lofty and light interiors exported as the Swedish ideal in the 21st century IKEA catalog (Fig. 1), the interior designs of the 1800s were dark and decorative, often furnished with extravagance and pomposity. (Fig. 2) As industrialism took root, however, it provided a new solution to home furnishing. This became a huge change for Swedes at the time; whereas the Swedish tradition had been for the elite classes to import products from abroad, the urban poor were used to constructing all furnishings on their own. In the era of industrialization, the two classes could both frolic in the newly created industrial products, aimed to imitate the prevailing design influences coming in from the rest of Europe. Despite their affordable price, however, these products were often mass-produced in cheaper materials and had generic decorations – and were thus viewed with disgust. (Söderholm 2005, 19)

Changing the Status Quo: Industrialism and the Birth of the Social Democratic Party

Despite the perceived inadequacy of the Swedish industrial product, industrialization laid base for the idea of democratic design through social democracy. Springing from the exploitation of labor amongst factory owners, labor unions started to appear in the 1870s. These advocated for a change in the Swedish status quo; at the time highly unjust and lacking any social welfare. During these times, it was not uncommon for laborers, both adults and children, to work long shifts – sometimes up to twelve hours – in a dirty and exposed environment. (Socialdemokraterna 2017) In 1889, several labor unions came together to form the Social Democratic party (SDP), planting the seeds of what would become the Swedish welfare state today. The SDP informed Sweden of its most important values today: democracy, equality, and socialism – all blended together into the core value of being lagom. For the industrial crafts, this meant something had to change.

Romanticizing the Home: the Larssons, Ellen Key, and the Arts and Crafts Movement

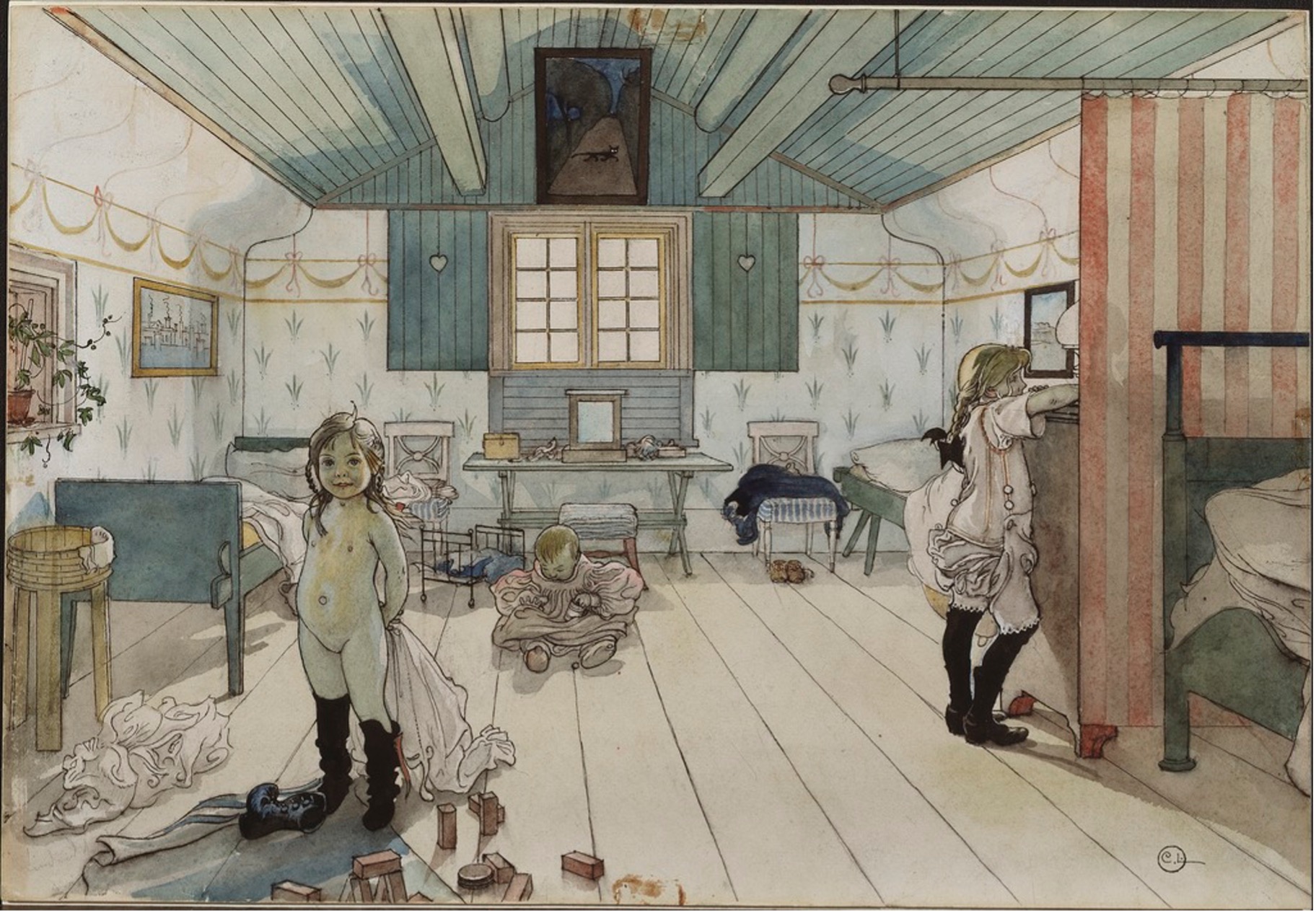

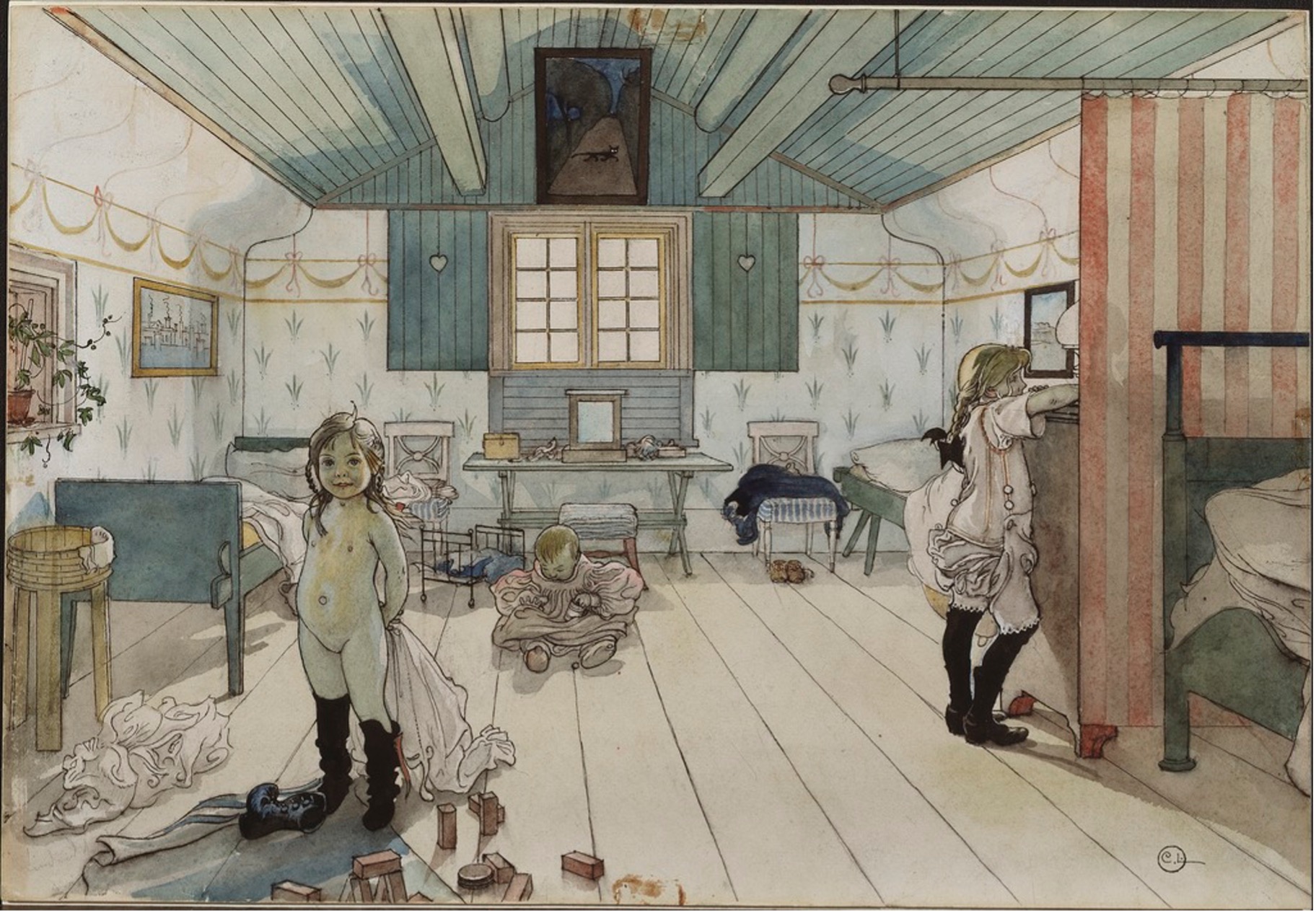

The matters that inspired the SDP’s core values of an equal and democratic state also circulated amongst players on Sweden’s cultural stage. (Söderholm 2005, 19-20) Directly opposing industrialization, these were ideas of romanticism, returning to traditional craftsmanship and folk style decoration. (Facos 1998, 65) One of the most influential groups of this time was the Arts and Crafts movement, established in the United Kingdom by William Morris in 1887. (Söderholm 2005, 16-19) Inspired by Britain’s leading art critic, John Ruskin, the Arts and Crafts movement advocated for art that paid great care to its material and remained free of excessive decoration. In their view, art was supposed to be ‘honest’ in its production, and practitioners of the movement strongly believed that it would be better to replace the low-quality mass-produced goods with those of fine craftsmanship. (Facos 1998, 65) Not only because of shoddy mass-produced products, the Arts and Crafts movement was also a protest against the nature of industry at the time. In Sweden, the influences of romanticism and the Arts and Crafts Movement can be most prominently seen in Lilla Hyttnäs, the home of artists Carl and Karin Larsson, that revolutionized the Swedish understanding of home life and home decoration. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3. Larsson, Carl. “Mammas och småflickornas rum.” Water color, 1897.

In Ett Hem. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1899.

Lilla Hyttnäs is an artistic statement: an egalitarian aesthetic in which the handmade coexists comfortably within the home. The home, designed entirely by the two Larssons, was a bold opposition to the dominant design influences in Sweden at the time. It opposed both the decorative neo-renaissance by being characterized by light, simple, and lofty interiors, as well as the industrial mass-production, by being completely handmade: Carl designed the furniture, and Karin wove and knitted various tapestries and textiles. The home was later captured in Carl Larsson’s 1899 book, “A Home,” which contained 24 watercolor paintings of intimate scenes from the Larsson’s everyday life. (Söderholm 2005, 42) “A Home” revolutionized the way Swedes conceived home life and home decoration by introducing the simple concept of domestic informality and comfort.

Published in the same year as “A Home,” Ellen Key’s “Beauty for All,” was one of the major components in Lilla Hyttnäs reaching public success. Key (1849-1926) was a feminist writer and a suffragist, who made a close connection between the Larssons’ home and its meaning for the home as a critical site for social reform. Despite her bourgeois background, Key meant that the neo-renaissance style of the time was “meaningless,” containing too much “kitsch and knick-knacks,” (Key 1899, 6) and complained that the concepts of “beauty” and “taste” were only extended to the upper classes. As such, Key wrote extensively of a revised meaning of beauty within the home, expanding the concept to reach everyday things, and often referencing Lilla Hyttnäs in the process. (Key 1899, 17) Lilla Hyttnäs was inexcessive and modest, yet contained everything that one could wish for in living a comfortable domestic life. To Key, this functionality only added to the home’s inherent beauty. (Murphy 2015, 69) She meant that it was possible to create a beautiful and comfortable environment through cheap and simple means and painted an alluring image of Lilla Hyttnäs as a representative of this. Because of Karin’s influence in the design and figuration of Lilla Hyttnäs, Key also turned to the average Swedish woman with an urging of doing the same. (Brunnström 2010, 74) Through the refashioning of the meaning of “beauty,” as well as a critique of the social organization of Sweden at the time, Key managed to spread the idea of the home as the site for instantiating aesthetic reform that would extend into the public. Throughout the years, so it did.

Converging with the Industrial: Vackrare Vardagsvara and the birth of the Bauhaus

Fig. 4. A kitchen unit by Gunnar Asplund at the Home Exhibition, 1917. Note the difference in decoration compared to fig. 1!

Unknown. Gunnar Asplunds förslag till bostadskök, 1917. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 3, 2019. https://digitaltmuseum.org/021107753838/utstallning-anordnad-av-svenska-slojdforeningen-senare-svensk-form-pa-liljevalchs.

The writings of Ellen Key and the image of Lilla Hyttnäs converged in the propaganda piece “Vackrare Vardagsvara” (transl. “More Beautiful Everyday Things”), written by Gregor Paulsson and published by the Swedish Handicraft Association in 1919. The oldest organization of its kind, the Swedish Handicraft Association (Svenska Slöjdföreningen) formed in 1845 as a non-profit organization tasked with promoting Swedish design nationally and internationally. Engaging with this task through different design exhibitions and movements, the SHA hosted the Home Exhibition in 1917, which became the start for Paulsson’s writings. In designing for the exhibition, all artists were prompted with designing with a cost limitation: a single room at max. 260kr, a single room and a kitchen for 600kr, and two rooms and a kitchen for 820kr. (Hedström 2001) The result was a showcase of 23 apartments and their respective interiors: a proof that design could be both affordable and beautiful. (Fig. 4) Extending these ideas, “Vackrare Vardagsvara” demanded that artists ought to work in direct collaboration with factories to produce high-quality everyday objects that could be accessible to everyone.

During the same year that Paulsson appealed for the beautification of everyday things, the Staatliches Bauhaus was founded. Published in April 1919, the Bauhaus manifesto urged for the unity of artists and craftsmen in a call for all artists to “return to the crafts!” (Wingler 1969, 31-33) Considering the similarities in the two manifestos – published in the same year and urging for a unity between arts and craftsmanship – it is quite surprising to consider that they remained largely unknown to each other at the time. Both movements were, however, highly influenced by the Deutscher Werkbund and their propagation for a collaborative enterprise between designers and craftsmen, blending art and industry.

II. THE INTERWAR YEARS: Entanglements of Socialism and Design

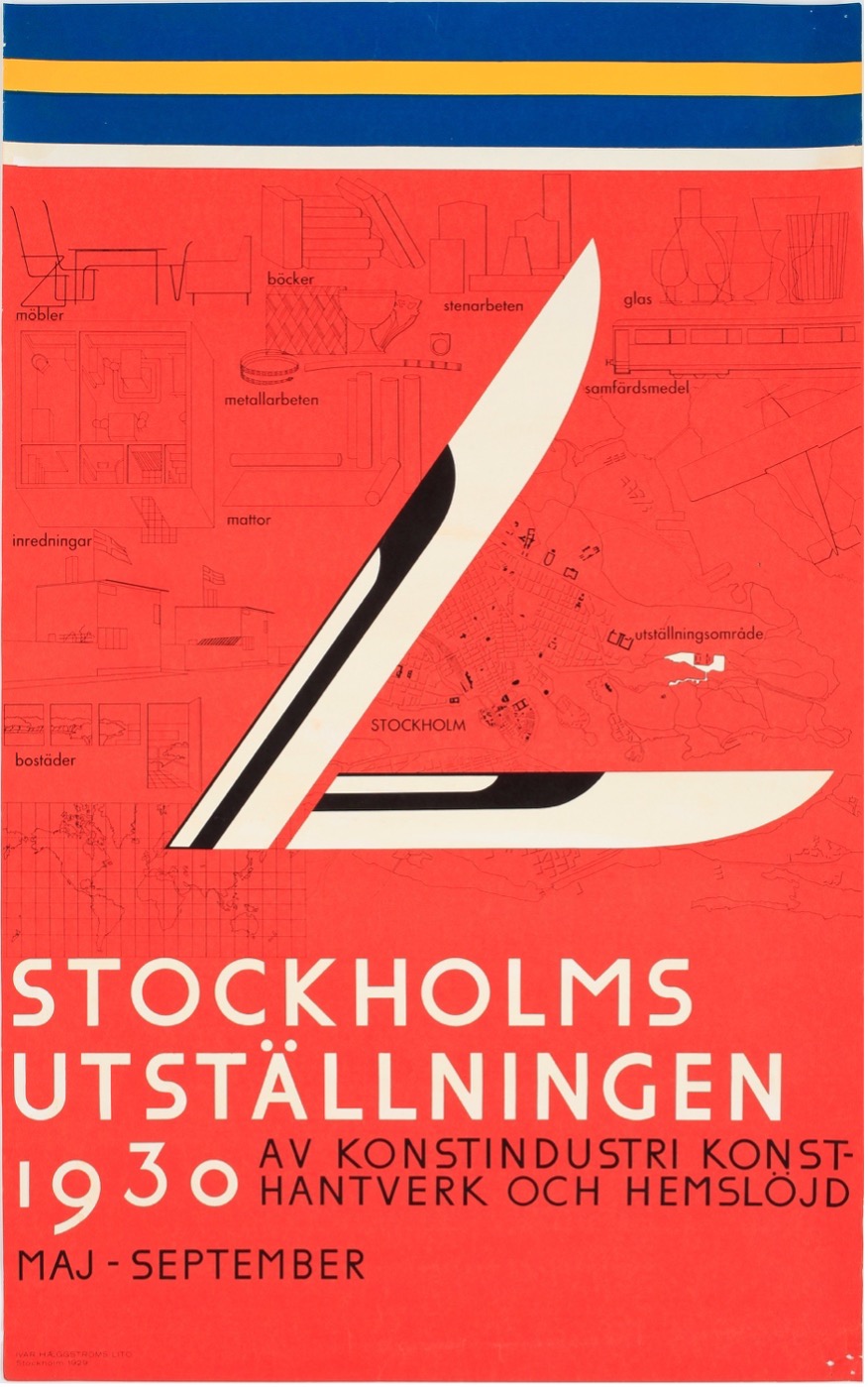

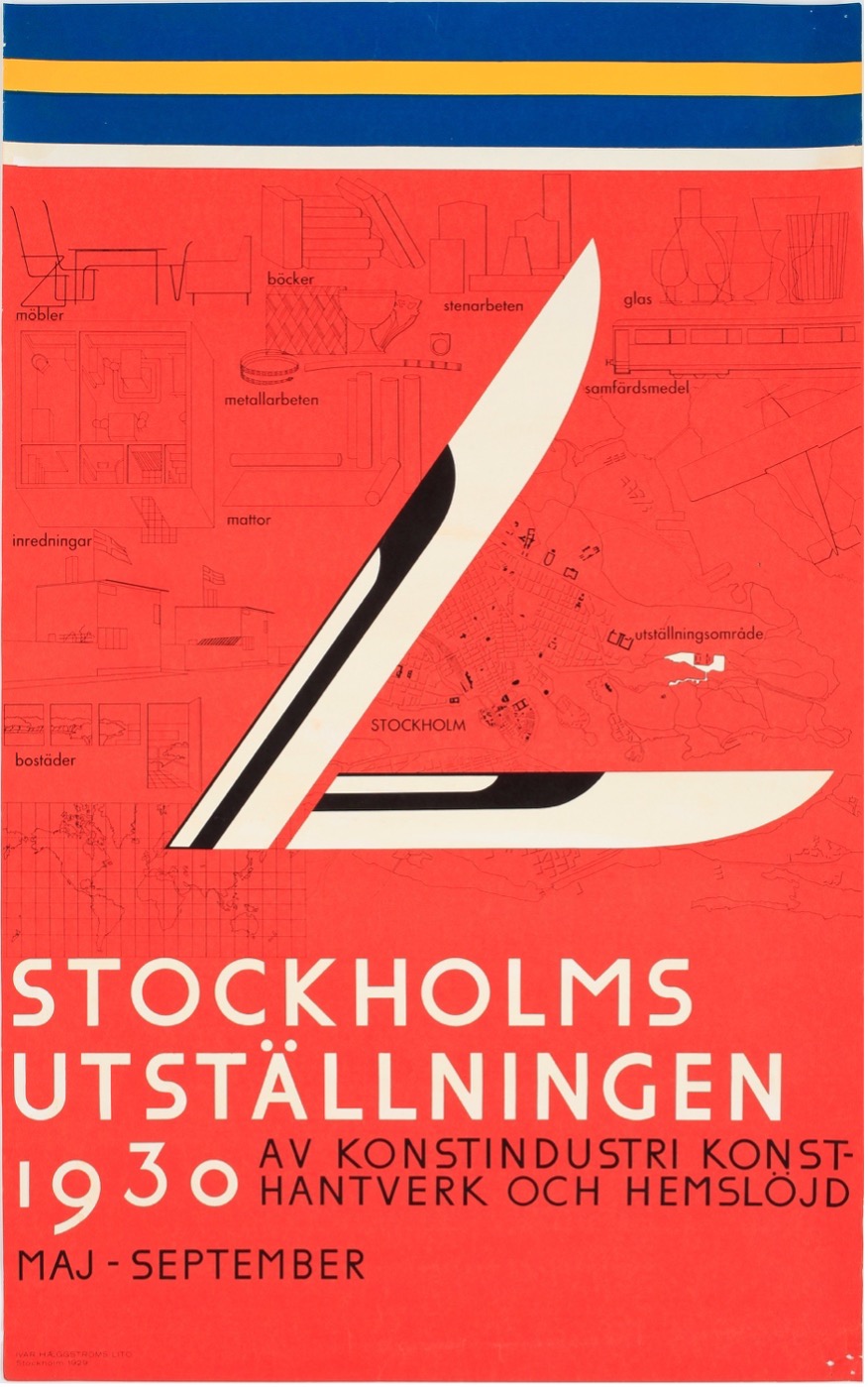

Fig. 5. Poster for Stockholm Exhibition 1930, created by architect Sigurd Lewerentz.

Lewerentz, Sigurd. “Stockholmsutställningen 1930 av konstindustri konsthantverk och hemslöjd maj- september."

In Svensk Designhistoria, 110. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010

Although Sweden was neutral in both

World Wars, the interwar period was still a defining time of change. During

this time, the support for the SDP was strongly increasing and the party formed

its first government in 1917, becoming the first ever social democratic party

in the world to take control of government through a democratic process. (Socialdemokraterna 2017) With the birth of the Bauhaus in 1919, it was also during the interwar years that

functionalism and modernity was brought to Sweden, introduced in the Stockholm

Exhibition of 1930. The

rise of social democracy and the introduction of functionalism are defining

moments in understanding how Swedish design has come to gain a certain political

vitality, important for our perception of the movement today.

The Bauhaus Legacy: The Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 and the Birth of Funkis

Fig. 6. A single family-unit a lá Carl Hörvik, exhibited at the Stockholm Exhibition at 1930, similar to the architecture of the Bauhauslers.

Hörvik, Carl. “Villa 40." In Svensk Designhistoria, 112. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010.

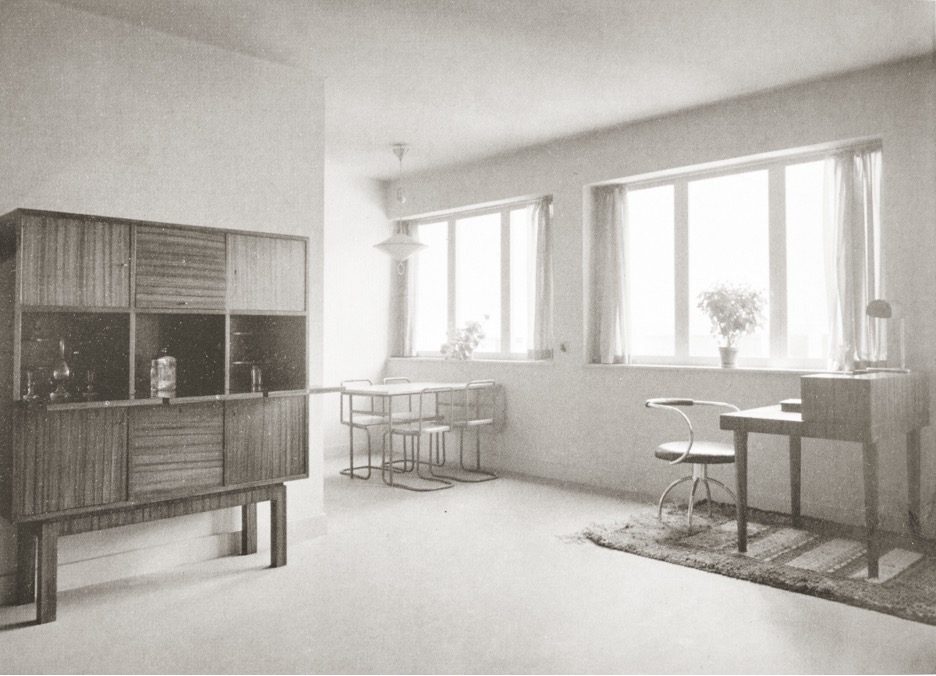

Another exhibition organized by Gregor Paulsson and the SHA, the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 materialized the new vision of modernity and was explicitly envisioned to be a forum of social change. (Murphy 2015, 177) With Paulsson as the main organizer, the exhibition focused on showcasing the “more beautiful everyday thing” and homes and home furnishings laid in the spotlight. Seeking inspiration from the Bauhaus and modernist icons such as France’s Le Corbusier and Russia’s Vladimir Tatlin, Swedish designers aimed to further the vision of modernity and functionalism that was already well-established in other parts of Europe. In many cases, they did so by imitation. The first thing presented to the public, the exhibition poster, had clear connections to the Bauhaus; made by architect Sigurd Lewerentz, painted in the bold color of red, and written in Lewerentz’ own sans serif. (Fig. 5) The dozen buildings showcased were highly similar to those of functionalist architecture as well, with white exteriors, big windows, and flat roofs. (Fig. 6) According to art critic Gotthard Johansson, these looked more like cardboard boxes or shacks rather than the villas and row houses they were aimed to represent. The houses also presented a new vision of interior design, including displays of home furnishings such as silverware, plates, and drinking glasses. These interiors were simple and non-ornamental, and included the introduction of tubular steel furniture, in Erik Lund’s interpretation of the tubular steel experiments taking place at the Bauhaus school in Dessau. (Fig. 7) These were, however, also met with skepticism and seen as too cold and austere to be brought into the home. Criticized by one of Sweden’s top interior designers at the time, Carl Malmsten, the interiors showcased at the exhibition were seen as too doctrinaire and non-traditional, lacking the ‘Swedishness’ that Malmsten deemed necessary for a home. (Brunnström 2010, 110-114) Despite harsh critique, however, the Stockholm Exhibition saw over four million visitors during its four month run, and the new style presented, termed “funkis,” continued to influence Swedish design for decades ahead. (Murphy 2015, 177)

Becoming Lagom, Becoming Swedish

The critique received at the Stockholm Exhibition wasn’t faced with complete dismissal, either. After all, it didn’t come out of nowhere. Sweden has always had a strong cultural norm of lagom, and in order for funkis to be fully accepted, it had to become lagom, too. Meaning “just right,” or “not too little and not too much,” lagom has prevailed as one of the dominant socialist ideals throughout Swedish history. Seen as the quintessential Swedish word, it is closely linked to the Swedish core value of equality. (Åsbrink 2018, 136-138) All should aim to be lagom – including, of course, design. For funkis to adhere to the concept of lagom, it had to listen to its critique and become less radical, softer, and more Swedish. Over the years to come, funkis was toned down and compensated and developed into a warmer strand of the more radical functionalism found in Western Europe. Blending with the earlier ideas of the good home, found in the Larssons’ Lilla Hyttnäs and Paulsson’s Vackrare Vardagsvara, and strongly connecting to the socialist value of lagom, funkis, at last, became accepted by the public.

The interwar years also saw an increase in both the use and the export of wood. While the export of wood had peaked during the late 1890s – with wood making up 40% of Sweden’s export – it had come to a stop at the outbreak of World War I. After the war ended, in 1918, the demand for Swedish wood soon increased again. In 1920, the export of timber was once again on par with the quotations that had applied before the war. (Björklund 1992, 64) With 70% of Sweden’s landscape consisting of forests, Swedes have always had “a special affinity for trees,” and already in 1893, Prince Eugen of Sweden (1865-1947) declared the Swedish national symbol to be the fir tree. (Facos 1998, 101) With trees already being an important source of pride for the Swedish, the rise in export of timber saw an increase in wooden products being produced by the Swedish state. Still to this day, Sweden is the third biggest provider of timber in the world, and wood is one of the most prominent building materials in designing houses, interiors, and furniture.

The rise of Socialism: Imagining Folkhemmet and the Swedish Welfare State

The success of funkis can thus be attributed to the new idea of “Swedishness” that was rising at the time. During its crystallization, it came to include a love for the forest, social democratic ideals, and the everlasting impact of lagom – and with the introduction of Folkhemmet, solidified into the often exported Swedish identity of today. Translated as “the People’s Home,” Folkhemmetwas a term coined by Per Albin Hansson – leader of SDP and prime minister of Sweden – in a 1928 radio speech. (Facos 1998, 66) In his famous speech, Hansson used the home as a metaphor for a better organized society:

Considering the low living standards in Sweden at the time, with cities being immensely dirty and congested due to the rapid urbanization following industrialization, Hansson’s speech was a call for action. In fact, one of the primary concerns of the SDP was the overcrowding of cities and the fast spread of diseases as a consequence of such. With a long history of tuberculosis and the attention for public health and sanitation increasing worldwide, SDP adopted the simple and cheap designs of functionalism as a solution for improving living conditions in an affordable manner. Today, Hansson and Folkhemmet are most known for establishing the Swedish welfare system; but another important, yet often overshadowed, aspect of folkhemmetis that it also became a foundational source of entanglements between Swedish politics and Swedish design.

Folkhemmet became a symbol and a vision for what Sweden currently was and had the potential to be; and as a result, the Swedish design world turned its gaze towards the home and its furnishings, eagerly designing for the Sweden of the future. (Fig. 8)

III. SWEDEN AFTER THE WAR: Realizing Folkhemmet and the foundation of IKEA

The interwar period in Sweden was one of incubation, planting ideas of functionalism and social democracy, and developing a vision of the Swedish future. The years following the second world war, on the other hand, saw a series of concrete changes. During this time, the Swedish economy was booming, and in 1950, Sweden was one of the fastest growing economies in the world.

90 Years of Peaceful Socialist Revolution

Sweden’s steady economic growth, under the lead of the SDP, enabled a social revolution that turned into a haven for social mobility. (Kristoffersson 2015, 76) The idea of the modern Swedish society was founded upon collective successes and the vision of a new Swedish identity; with the emergence of the social welfare system followed a sense of national pride. The SDP, ruling Sweden almost completely uninterruptedly from 1917-1976, worked hard not just to create material security, but also to enable emotional stability and a feeling of belonging amongst the Swedish population. (Larsson och Molander 2019) For the social democrats, the most important thing was to fight class divisions and to level the Swedish population. During their long rule, they implemented several socialist reforms – free education, child benefits, the public unemployment insurance fund, regulations of housing standards, and free public healthcare – that realized a socio-economic security to a greater degree than most other nations. During their rule, the SDP aimed to promote an equality of the highest standards rather than an equality of minimal needs. For housing, this meant no singling out of low-income families and no subsidized housing program being implemented – as was the case in many other nations in Europe. (Rudberg 1992, 26) Instead, everyone was envisioned to live in the same identical housing unit – no matter their social class – and so, Folkhemmet became a reality.

The Materialization of Folkhemmet

Fig. 9. One of the most well-known examples of star house architecture: the ‘Gröndal’ neighborhood in Stockholm,

designed by Leif Reinius and Sven Backström, built during the folkhem era.

Bladh, Oskar. Stjärnhus och terrasshus i Gröndal Exteriör. 1962. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 5, 2019. https://digitaltmuseum.se/011015009396/stjarnhus-och-terrasshus-i-grondal-exterior-flygbild-over-grondal-stjarnhus.

During the post-war years, Folkhemmetmoved from being a metaphorical concept into a reality. Between 1945 and 1960, 900,000 homes were built in Sweden. (Olsfelt 2011) With a focus on the multi-family unit, it was in the materialization of Folkhemmet that the functionalist influences from the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition really started being appropriated and re-imagined. Seeking to improve the highly congested living conditions that had prevailed in Sweden, the new housing focused on providing space and light for all citizens in the folkhem era. The new units were regulated to be big enough to not host more than two people in the same room; a family of four, for example, would have to live in a tenement of two-rooms and a kitchen to not classify as living in a cramped manner. With large areas of Sweden being famously dark and cold for long months of the year, there was also an emphasis on light, and every apartment had to receive some daylight throughout the day. (Thörn 1997, 410) In order to accommodate for these regulations, the star house (stjärnhus) was invented by architects Sven Backström and Leif Reinius. (Larsson och Molander 2019, 19) An apartment complex of three to four floors, the star house was one of the most popular buildings of the folkhem era and can be easily spotted in Swedish cityscapes today. The name of the buildings stem from their form and construction, being a structure of three houses joined together in the shape of a three-pointed star with a common stairwell in the middle. Because of the building’s shape, each apartment in the star house has windows facing in three directions. Each star house could then be connected to other star houses, creating hexagonal structures enclosing a courtyard protected by six walls. (Figure 9) Other popular structures during the folkhem era were row houses and semi-detached houses, which provided sufficient space while being cheap in construction.

Fig. 10. Classic folkhem architecture: the multi-family dwelling with earthy-colored facades and a small courtyard. In Rosta, Örebro.

Nelsäter, Hans. “Rosta, Örebro." In Folkhemmets Byggande, 84. Uppsala: Svenska Turistföreningen, 1992.

In contrast to the buildings that had been shown at the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition, the architecture of Folkhemmet was more playful. Rather than the Bauhaus-inspired buildings – flat-roofed and with white exteriors – the houses of Folkhemmet saw a regression in terms of style, with elements from the era of national romanticism once again being emphasized. The new buildings saw the return of the traditional gable roof and were, despite the survival of the functionalist non-ornamental exterior, more expressive. The new facades were accentuated by balconies and bay windows – which both had functional purposes – and were painted in earthy tones of red, yellow, and green. (Fig. 10) Instead of being purely decorative, the new accentuation had its own purpose and reason for being there, while simultaneously giving the building its own character. (Rudberg 1992, 72-73) Thus, despite becoming more expressive, the architecture of Folkhemmet still remained some of the most important ideals from the functionalism of the 1930s, such that less is more, and that form follows function.

The New Interior

The era of Folkhemmet also generated a new way of living, following the writings of Ellen Key. The new functionalist approach, emphasizing simple and non-decorative forms, was seen as practical and sanitary – and thus, in Key’s writings, beautiful. During the build of Folkhemmet, several housing studies were carried out by the state. Whereas the highly congested way of living was a known fact, the studies revealed that many families in fact chose to live in this way. Instead of spreading out in the home, many families crammed together when time came to sleep, giving rise to the new notion of “voluntary overcrowding.” (Brunnström 2010, 158) One example describes: “the whole family – five people – slept in the compact space of 10.5m2, while double-sized beds in both the living room and kitchen remained unused.” (Brunnström 2010, 158) The studies also revealed that furniture was often chosen on the basis of impressing friends and acquaintances rather than fulfilling a functional purpose within the home, and that parlors were reserved for the sole purpose of hosting guests and parties, remaining unused in the family’s everyday life.

During the post-war years, home furnishing became an issue of public education and several courses in home decoration were offered throughout Sweden. (Kristoffersson 2015, 82) In the new Sweden, everyone ought to know how to utilize their home in a functional manner – and remain good taste in the process – and home decoration became an issue of democracy and civil society.

The 17-Year-Old Businessman: Ingvar Kamprad and his IKEA

A common saying in Sweden is that “Per Albin Hansson built the folkhem, Ingvar Kamprad furnished it.” (Söderholm 2005, 10) As new ideas of home life and home decoration expanded, the need for designs that were accessible to everyone increased. Since the folkhem was meant to house all of Sweden – despite differences in socio-economic class – its interior had to be both tasteful and cheap. In 1946, the state inquired for furniture that could “satisfy the consumer’s needs for good furniture at the lowest possible price.” (Goude et al, 1949) At that, IKEA was born.

An acronym of his name and birthplace – Ingvar Kamprad Elmtaryd Agunnaryd – Ingvar Kamprad founded IKEA at the sole age of 17. Despite his young age, Kamprad had since long had a mind for business. Famously, already before the age of five, Kamprad had earned his first money by selling matches to his neighbors. At IKEA’s founding in 1943, the company sold small knick-knacks that Kamprad had acquired cheaply elsewhere, like watches, pens, wallets, and seeds, and it wasn’t until 1948 that Kamprad started selling home furnishings, inspired by the furniture sold by a local rival. (Söderholm 2005, 215) Today, IKEA is the world’s biggest furniture retailer, with over 420 stores operating in 52 countries. (IKEA 2019) Based on nine principles formulated by Kamprad in 1976:

IKEA has become synonymous with Swedish identity and the strong Swedish core values of egalitarianism and the welfare system. (Collins 2011, 7) Today, one of IKEA’s most advertised slogans is one of “democratic design.” Coining the term in 1995, democratic design is “design for everyone,” and “brings good design to the many people by providing well-designed home furnishing solutions, with great form and function, high quality, built with a high focus on sustainability and at an affordable price.” (IKEA 2019) Despite this, Ingvar Kamprad is notorious for his cheap nature, known for driving “a beat-up Volvo” and “pocket[ing] the salt and pepper packets at restaurants” while, before his death in 2018, being the fifth richest person in the world. (Collins 2011, 11) Despite this comical contradiction, Kamprad’s competitive hyper-capitalist personality has played a defining role in the socialist ethos of design democracy that prevails in Sweden today.

Behind the Design: Imitation, Practice, and Discovering Flat Packaging

Although the success of IKEA is often attributed to the exceptional personality of Ingvar Kamprad, it ought to also be ascribed to the influences of the Bauhaus and its functionalism. If it hadn’t been for the introduction and development of funkis following the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, IKEA wouldn’t be what it is today. (Kristoffersson 2015, 76)

In the economic boom of the 1950s, with the build of Folkhemmet and a rationalization of industry, Kamprad sought to mass-produce home furnishings in the cheapest way possible. One of the biggest inspirations were the simple and geometric forms imagined at the Bauhaus. Despite – or maybe, because of – their status as radical, exclusive, and highly sought-after, many of the Bauhaus objects never made it to mass-production, although being imagined doing so, both under the lead of Walter Gropius and later, Hannes Meyer. These prototypes were instead picked up by Kamprad, whom instead of becoming a design pioneer looked back into history and aimed to improve other designers’ failed attempts of success. Perhaps most notably, one of the most popular IKEA products, the POÄNG, designed by Noboru Nakamura in 1977, (Fig. 11) makes strong connections to Marcel Breuer’s Long Chair in its simple yet ergonomic form. (Fig. 12) Breuer’s tubular steel furniture also became a withstanding influence amongst the IKEA designers, such as Charlotte Rude and Hjördis Olsson-Une, who appropriated Marcel Breuer’s technique for their GOGO and JENKA, deriving from Breuer’s creations in a new use of bold colors. Similarly, the embracing of modular design that happened at the Bauhaus also became established in IKEA’s design vision, with IKEA’s most sold product, the BILLY bookshelf, being a good example of this. (Fig. 13) By producing furniture in a modular fashion – abstracting objects into simple shapes that can be manufactured in massive quantities at minimum cost – IKEA managed to keep production costs down in their design. At the same time, most IKEA furniture is available in several different colors and materials – all to suit the style of the buyer. POÄNG, for example, features a variety of versions. The varying versions of each product highly enhances its ability to suit each customer’s personal taste. Perhaps you would really want the bright red polyester chair cushion with the light wood armrests, or perhaps an all-black chair with a leather cushion fits you better. Even though the POÄNG will always have the same shape, users can personalize their own chair through a range of different option. Same, same, but different. (Fig. 11)

Fig. 11. The IKEA classic, “POÄNG,” in a variety of colors and materials. This is only 8 versions – out of 72.

IKEA. ”POÄNG.” Digital image. IKEA. Accessed May 20, 2019. https://m2.ikea.com/se/sv/sok/?q=po%C3%A4ng%20.

Fig. 12. Marcel Breuer's "Long Chair", a precursor to IKEA's POÄNG.

Breuer, Marcel. “Long Chair.” 1935-1936. The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Accessed May 5, 2019. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/83922/.

The use of wood has also been a

defining factor in IKEA’s design successes, with 60% of the collection being

designed in this natural material. (IKEA 2019) The use of wood stems both from the idea of Swedishnessthat arose in Sweden during the post-war years, as well as from wood being a cheap and relatively light material that is easy

to work with. Sweden has a long tradition of the wooden handicrafts – with woodwork being a

compulsory subject in Swedish schools starting from third grade – and the

wooden furniture of IKEA instantly became popular. Today, the use of wood

within the home is highly associated with Scandinavian design, and today, IKEA

uses an astounding 1% of the commercial lumber supply of the world, with a goal

of “all wood com[ing] from more sustainable sources, defined as recycled or

FSC® certified wood, by 2020.” (IKEA 2019)

Fig. 13. The modularity and the difference sizes, colors, and styles of the BILLY bookshelves make them easy to personalize.

IKEA. “BILLY.” Digital image. IKEA. Accessed May 18, 2019. https://www.ikea.com/us/en/catalog/categories/series/28102/.

Furthermore, Kamprad, always looking for ways to cut costs, realized the concept of flat packaging in 1956, which became revolutionary for the company. The flat packages saved an enormous amount of space and made both production and transportation of products cheaper. The flat packaging also increased the prominence of wood within IKEA’s collection, as wood is easy to flatten and later re-assemble. The flash of genius happened when Kamprad and his employee, designer Gillis Lundgren, were transporting Lundgren’s newly designed table, LÖVET. When trying to cram the table in the trunk of the car, Lundgren is said to have complained that the table took up too much space and suggested that they take off the table legs to save space. The legs were later reassembled when Lundgren and Kamprad reached their final destination, and flat packaging was born. (Söderholm 2005, 215) (Fig. 14)

Fig. 14. IKEA’s flat packaging of ready-to-assemble furniture makes them easy to transport. In 2012, IKEA launched a bikeshare, where bikes like the one above can be rented to transport goods home in a safe, cheap, and sustainable way. IKEA. “IKEA-konceptet.” Accessed May 4, 2019. https://www.ikea.com/ms/sv_SE/this-is-ikea/the-ikea-concept/

Behind the Success: the IKEA Catalog and the Export of Swedishness

Every year, 203 million copies of the IKEA catalog are printed and distributed in 35 different languages across the world,making it one of the most well-read books in the world together with the Bible, the Quran, and Harry Potter. (Weller 2017) Magnificent in its marketing, IKEA aims to sell by presenting its products in intimate scenes of private life – much like how Carl Larsson presented Lilla Hyttnäs in “A Home,” published in 1899. Depicting rooms completely furnished with IKEA products, these room sets are paid an incredible amount of detail and always contain a layer of voyeurism to them: “just as the goal of a real room is to look like a fake one, the goal of a fake room is to look like a real one.” (Collins 2011, 20) Furthermore, what is so genius about the IKEA catalog is the small cultural specific tweaks in each scene. In an interview with IKEA Communications, where the catalogue is produced, the managers explain:

In this way, IKEA manages to appeal and be relatable to large amounts of people all over the world, exporting ideas of Sweden and Swedishness in the meantime.

Fig. 15. An American demonstration in support of a gay couple portrayed in the IKEA catalog in 2000.

“Sverige åt Alla! SVENSKHET.” In IKEA the Book, 199. Stockholm: Arvinius Förlag AB, 2010.

With a facade of blue and yellow, furniture with Swedish names, and a food canteen of Swedish delicacies, IKEA has managed to commodify Swedish culture. For non-Swedes visiting the store, an idea of Sweden is created – and for Swedes who can recognize the names and meals sold in the canteen, IKEA produces a feeling of national pride, no matter its actual location. A closer look reveals not only an exportation of the national colors and foods, however, but also subtler yet important – and sometimes, controversial – narratives of Swedishness. One of the simplest examples of this is the ready-to-assemble furniture. Having the consumer partake in the ‘production’ of their goods, IKEA underscores the Swedish idea that success relies on hard work and frugality. (Åsbrink 2018, 101-110) Another is the exportation of cultural moral values in the scenes of the IKEA catalog, often featuring an emphasis on feminism, and the acceptance of both the multicultural, as well as the LGBTQ+ community. (Fig. 16) Lastly, of course, the idea of creating affordable products for the masses is linked closely to Folkhemmetand the equality that has defined and promoted the Swedish welfare state. With a slogan of democratic design, IKEA has managed to appropriate and export the ideas of beauty and the everyday – a lá Ellen Key and Gregor Paulsson – to the rest of the world. With 957 million in-store- and 2.5 billion web visits every year, IKEA has successfully made design available to the masses, realizing one of the fundamental goals of the Bauhaus. (IKEA 2018)

V. FROM MODEST NOVELTY TO GLOBAL PHENOMENON

The story of Swedish design doesn’t end here. With IKEA being the world’s biggest furniture retailer, (Loeb 2012) Swedish clothing company Hennes & Mauritz (H&M) being the world’s second-largest clothing retailer, (Industry Ranking 2018) and Swedish application Spotify being the world’s most popular music service, (Dagens Industri 2015) Sweden is constantly spreading its philosophy and aesthetics into the rest of the world. Swedish design has proved the beauty of functionality and the concept of “less is more,” while being ‘democratic’ and accessible through the production of cheap, yet beautiful, products.

Sweden thus dominates several fields of the global design consumption today, making the export of Swedishness widespread. Based on ideas rising in 1800s industrial Sweden, Swedishness is deeply rooted in values of social democracy, equality, and lagom. Considering how the ideal of Swedishness has formed, shaped by key figures such as Ellen Key and Gregor Paulsson, inspired by artistic movements such as the Arts and Crafts and the Bauhaus, and envisioned in the idea of Folkhemmet and the concept of IKEA, it is quite fascinating that Swedishness has been exported in the grand manner it has today. What started off as a modest local production, focused on the national romantic ideals of the home, has become a global phenomenon that millions of people, worldwide, are exposed to on a daily basis. Yet, few people can name any Swedish creators, pioneers, and designers – even in Sweden. Rather than knowing the names of Ingvar Kamprad, Erling Persson, Daniel Ek, and Martin Lorentzon, their inevitable presence in our lives manifest only in the ordinariness of our comfort. In a quiet promotion of social democracy, the collective unit supersedes the singular person, remaining humble rather than elevating status and building hierarchies; and perhaps this is what Swedishness looks like in its essence. In the Swedish stuff of life, everything has acquired a certain political vitality, and a message of “people’s needs, instead of luxury needs.”

Bengtsson, Staffan. IKEA the Book. Stockholm: Arvinius Förlag AB, 2010.

Björklund, Jörgen. “Skogsindustrins utveckling före andra världskriget: Några perspektiv på Västerbottens Län.” In Skogsindustrins utveckling och förändring ed. Per-Ove

Bäckström, 61–69. Stockholm: Kungliga Skogs- och Lantbruksakademien, 1992.

Booth, Michael. The Almost Nearly Perfect People: Behind the Myth of the Scandinavian Utopia. London: Random House UK, 2014.

Buchanan, Richard. “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking.” Design Issues 8, no. 2 (Spring 1992): 5-21.

Collins, Lauren. “House Perfect: Is the IKEA Ethos Comfy or Creepy?”The New Yorker, September 26, 2011.

Dagens Industri. “Det är Sveriges mest värdefulla varumärke.” Dagens Industri, August 8, 2018, https://www.di.se/nyheter/det-ar-sveriges-mest-vardefulla-varumarke/.

Facos, Michelle. Nationalism and the Nordic Imagination: Swedish Art of the 1890s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Fast Retailing. “Industry Ranking.” Last modified November 21, 2018. https://www.fastretailing.com/eng/ir/direction/position.html.

Goldberg, Daniel. ”Nu är Spotify störst i världen.” Dagens Industri, December 2, 2015.

Goude, Nils, Elsa Appelquist, Greta Bergström, Hugo Edstam, Allan Hernelius, Carl G. Lundberg, Signe Silow. Kvalitetsforskning och konsumentupplysning: betänkande / avgivet den 19 maj 1949 av 1946 års utredning angående kvalitetsforskning och konsumentupplysning. Stockholm: Handelsdepartementet, Statens Offentliga Utredningar, 1949.

Gundtoft, Dorothea.Ny Nordisk Design. Lund: Historiska Media, 2015.

Hansson, Per-Albin. “Folkhemstalet.” Speech, Stockholm, January 18, 1928. Svenska Tal. http://www.svenskatal.se/1928011-per-albin-hansson-folkhemstalet/.

Hedström, Sara. “Svensk Form: About the Swedish Form.” Master's thesis, Linköping University, 2001. Retrieved from https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:18632/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Helliwell, John F, Richard Layard and Jeffrey D. Sachs. World Happiness Report 2019. New York: United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Accessed May 20, 2019. https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2019/.

IKEA, “Democratic Design.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/this-is-ikea/democratic-design-en-gb/.

IKEA. “IKEA Facts and Figures 2018.” Accessed May 16th, 2019. https://highlights.ikea.com/2018/facts-and-figures/home/.

IKEA, “Vi älskar trä.” Last modified April 12, 2011. Accessed May 20, 2019. https://www.ikea.com/se/sv/about_ikea/newsitem/vi_alskar_tra.

IKEA. “Wood.” Accessed May 20, 2019. https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/this-is-ikea/people-planet/energy-resources/wood/.

IKEA Museum. “150 år av nyfikenhet! Från 1943 till 2018 och 75 år in i framtiden.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://ikeamuseum.com/sv/ikea-75.

Key, Ellen. Skönhet för Alla: Fyra Uppsatser. Stockholm: Rekolid, 1996.

Kristoffersson, Sara. IKEA: En Kulturhistoria. Stockholm: Atlantis, 2015.

Larsson, Ulf and Lisa Molander. Efterkrigstidens bostadsbebyggelse: Rapport från Etapp I. Skara: Västergötlands Museum, 2009. Accessed May 15, 2019. https://www.vastarvet.se/siteassets/vastarvet/kunskap-o-fakta/efterkrigstidensbostadsbebyggelseetapp1.pdf.

Loeb, Walter. “IKEA is a World-Wide Wonder.” Forbes, December 5, 2012.

Lupton, Ellen, and J. Abbott Miller. the abcs of ∆❍❏ the bauhaus and design theory. Hudson: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.

Murphy, Keith M. Swedish Design: An Ethnography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Olsfelt, Anna. “Grannskapstorg som fenomen - med fallstudien Axel Dahlströms torg.” Master's thesis, Gothenburg University, 2011. Retrieved from https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/26867/1/gupea_2077_26867_1.pdf.

Paulsson, Gregor. Vackrare Vardagsvara.Gothenburg: Svenska Slöjdföreningen, 1919.

Rudberg, Eva. Folkhemmets Byggande: Under Mellan- och Efterkrigstiden. Uppsala: Svenska Turistföreningen, 1992.

Schuldenfrei, Robin. Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900 -1933. Hudson: Princeton University Press, 2018.

Schwab, Klaus. The Global Gender Gap Report 2018. Geneve: World Economic Forum. Accessed May 20, 2019. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf.

Socialdemokraterna. “Vår Historia.” Last modified March 21, 2017. https://www.socialdemokraterna.se/vart-parti/om-partiet/var-historia/.

Statista. “Number of IKEA catalogs printed per year worldwide from 1951 to 2017 (in millions).” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/268131/number-of-printed-ikea-catalogs-per-year-worldwide/.

Söderholm, Carolina. Svenska Formgivare. Lund: Historiska Media, 2005.

Torekull, Bertil. Historien om IKEA: Ingvar Kamprad berättar för Bertil Torekull. Stockholm: Wahlstrand och Wihlstrand, 2006.

Thörn, Kerstin. En bostad för hemmet: idéhistoriska studier i bostadsfrågan 1889-1929. Umeå: Umeå University, 1997.

Weller, Chris. “IKEA’s Catalog is as popular as the Bible and the Quran.” Business Insider, July 28, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/ikea-catalog-as-popular-bible-quran-2017-7?r=US&IR=T.

Wingler, Hans M. The Bauhaus: Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Chicago, ed. Joseph Stein. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1969.

Åsbrink, Elisabeth. Orden som formade Sverige.Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, 2018.

Fig. 1. The cover of the 2019 IKEA Catalog. IKEA. ”Pressbilder IKEA katalogen våren 2019.”

Digital image. IKEA. Accessed May 5, 2019. https://press.ikea.se/katalogen_varen2019/.

One of the greatest examples of the realization of Bauhaus’ goals and aspirations can be found in the region of Scandinavia. In the past decade, Scandinavia has overflown with praise from countries all over the world. Labeled by British author Michael Booth as a “nearly perfect people,” (Booth 2014, 1) the Scandinavians have continuously topped the World Chart indexes in happiness and equality. (Helliwell, Layard and Sachs 2019) As “the Nordic Model” has become a common topic of discussion; and as a dozen of books focusing on the Scandinavian concepts such as the Finnish sauna, the Swedish “lagom,” and the Danish and Norwegian “hygge” have been published, Scandinavia has taken the world by storm.

In the design world, Scandinavia has long had a seat at the table, with Sweden at the forefront, strongly influencing the increasing popularity of Scandinavian design. Although a nation of only 10 million inhabitants, Sweden has managed to have a far-stretched global outreach within the field of design by alluding to its founding principles of design work and the success of its biggest design company, the home-furnishing IKEA. (Dagens Industri 2018) With Sweden at the forefront, the concept of Scandinavian Design has become so notable that it has claimed its own name: The New Nordic. Influenced by the nature of the Bauhaus, seeking to combine function and form in a simple and minimalist way, The New Nordic also encompasses an added layer of hygge that has traditionally been very important in Scandinavian homes. (Gundtoft 2015, 10-11) With everything in moderation, these two opposing strands come together to encompass both the Swedish vision of lagom, while simultaneously giving Sweden an international superstar status within the design world. Yet, despite the chic and state-of-the-art Swedish identity that has been advertised globally over the past few years, Swedish design has remained unobtrusive and modest, permeating society in an intuitive and almost unnoticeable way. Continuously striving for egalitarianism, Swedish design has chosen to remain humble rather than to elevate status and build hierarchies; similarly to the Bauhaus focusing rather on “people’s needs rather than luxury needs.” Everything that is accessible to one person should also be available to the other – no matter their social differences. In the Swedish stuff of life, everything has acquired a certain political vitality in its quiet promotion of social democracy. Behind the exported ideas of hygge, lagom, and Swedish superstar companies such as IKEA and H&M, lies an entire nation to be explored and discovered; one of humility and reticence.

When exploring Sweden’s design history, the concept of Swedishness takes root in a synthesis of social democracy, design movements, and creative pioneers. This paper will argue that Sweden grew from a modest novelty into a global phenomenon by realizing Bauhaus’ goal of making design available to the masses, and that the functionalist influences that Bauhaus brought to Sweden were essential in completing this quest. In conceptualizing Swedish design, the convergence of the Bauhaus with national ideals and politics has been crucial; and without it, the export of Swedishness might have never succeeded.

- IDEAS OF THE GOOD HOME: Sweden in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century

Fig. 2. Alberget 4B, Stockholm, in 1890, an upper-class dwelling in neo-renaissance style.

Orling, B. Alberget 4B, interiör i Rydbergska stiftelsens hus. Digitala stadsmuseet.

Accessed May 3, 2019. http://digitalastadsmuseet.stockholm.se

The birth of Swedish design can be traced back to the 1800s, with the first ever international showcase of Swedish design taking place at the Great Exhibition of London in 1856. The Great Exhibition was the first ever world fair, hosting over six million visitors during its six month showcase. Sweden’s participation in the expo was meager, dominated by different samples of wood and steel. Unnoticed by the rest of the world at the time, it would take another 50 years for Sweden to fully re-enter into the international playing field of design – largely because of the advancement of industrialism. (Brunnström 2010, 21-24)

With the first Swedish woodwork factory built during the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851, it wasn’t until the latter part of the 1800s that industrialization really prospered. During this time, Sweden was, despite its current egalitarian status, highly unequal; and the Swedish elite sought outwards in satisfying their taste for design. (Kristoffersson 2015, 76) Dominated by the neo-renaissance and neo-rococo influences of the rest of Europe, it was not uncommon for the upper classes to house interior designs inspired by the French rococo with porcelain imported from the Dutch East Indies on display. (Brunnström 2010, 55) As one might imagine, Swedish design in the 1800s was almost opposite to its common perception today. Instead of the lofty and light interiors exported as the Swedish ideal in the 21st century IKEA catalog (Fig. 1), the interior designs of the 1800s were dark and decorative, often furnished with extravagance and pomposity. (Fig. 2) As industrialism took root, however, it provided a new solution to home furnishing. This became a huge change for Swedes at the time; whereas the Swedish tradition had been for the elite classes to import products from abroad, the urban poor were used to constructing all furnishings on their own. In the era of industrialization, the two classes could both frolic in the newly created industrial products, aimed to imitate the prevailing design influences coming in from the rest of Europe. Despite their affordable price, however, these products were often mass-produced in cheaper materials and had generic decorations – and were thus viewed with disgust. (Söderholm 2005, 19)

Changing the Status Quo: Industrialism and the Birth of the Social Democratic Party

Despite the perceived inadequacy of the Swedish industrial product, industrialization laid base for the idea of democratic design through social democracy. Springing from the exploitation of labor amongst factory owners, labor unions started to appear in the 1870s. These advocated for a change in the Swedish status quo; at the time highly unjust and lacking any social welfare. During these times, it was not uncommon for laborers, both adults and children, to work long shifts – sometimes up to twelve hours – in a dirty and exposed environment. (Socialdemokraterna 2017) In 1889, several labor unions came together to form the Social Democratic party (SDP), planting the seeds of what would become the Swedish welfare state today. The SDP informed Sweden of its most important values today: democracy, equality, and socialism – all blended together into the core value of being lagom. For the industrial crafts, this meant something had to change.

Romanticizing the Home: the Larssons, Ellen Key, and the Arts and Crafts Movement

The matters that inspired the SDP’s core values of an equal and democratic state also circulated amongst players on Sweden’s cultural stage. (Söderholm 2005, 19-20) Directly opposing industrialization, these were ideas of romanticism, returning to traditional craftsmanship and folk style decoration. (Facos 1998, 65) One of the most influential groups of this time was the Arts and Crafts movement, established in the United Kingdom by William Morris in 1887. (Söderholm 2005, 16-19) Inspired by Britain’s leading art critic, John Ruskin, the Arts and Crafts movement advocated for art that paid great care to its material and remained free of excessive decoration. In their view, art was supposed to be ‘honest’ in its production, and practitioners of the movement strongly believed that it would be better to replace the low-quality mass-produced goods with those of fine craftsmanship. (Facos 1998, 65) Not only because of shoddy mass-produced products, the Arts and Crafts movement was also a protest against the nature of industry at the time. In Sweden, the influences of romanticism and the Arts and Crafts Movement can be most prominently seen in Lilla Hyttnäs, the home of artists Carl and Karin Larsson, that revolutionized the Swedish understanding of home life and home decoration. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3. Larsson, Carl. “Mammas och småflickornas rum.” Water color, 1897.

In Ett Hem. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1899.

Lilla Hyttnäs is an artistic statement: an egalitarian aesthetic in which the handmade coexists comfortably within the home. The home, designed entirely by the two Larssons, was a bold opposition to the dominant design influences in Sweden at the time. It opposed both the decorative neo-renaissance by being characterized by light, simple, and lofty interiors, as well as the industrial mass-production, by being completely handmade: Carl designed the furniture, and Karin wove and knitted various tapestries and textiles. The home was later captured in Carl Larsson’s 1899 book, “A Home,” which contained 24 watercolor paintings of intimate scenes from the Larsson’s everyday life. (Söderholm 2005, 42) “A Home” revolutionized the way Swedes conceived home life and home decoration by introducing the simple concept of domestic informality and comfort.

Published in the same year as “A Home,” Ellen Key’s “Beauty for All,” was one of the major components in Lilla Hyttnäs reaching public success. Key (1849-1926) was a feminist writer and a suffragist, who made a close connection between the Larssons’ home and its meaning for the home as a critical site for social reform. Despite her bourgeois background, Key meant that the neo-renaissance style of the time was “meaningless,” containing too much “kitsch and knick-knacks,” (Key 1899, 6) and complained that the concepts of “beauty” and “taste” were only extended to the upper classes. As such, Key wrote extensively of a revised meaning of beauty within the home, expanding the concept to reach everyday things, and often referencing Lilla Hyttnäs in the process. (Key 1899, 17) Lilla Hyttnäs was inexcessive and modest, yet contained everything that one could wish for in living a comfortable domestic life. To Key, this functionality only added to the home’s inherent beauty. (Murphy 2015, 69) She meant that it was possible to create a beautiful and comfortable environment through cheap and simple means and painted an alluring image of Lilla Hyttnäs as a representative of this. Because of Karin’s influence in the design and figuration of Lilla Hyttnäs, Key also turned to the average Swedish woman with an urging of doing the same. (Brunnström 2010, 74) Through the refashioning of the meaning of “beauty,” as well as a critique of the social organization of Sweden at the time, Key managed to spread the idea of the home as the site for instantiating aesthetic reform that would extend into the public. Throughout the years, so it did.

Converging with the Industrial: Vackrare Vardagsvara and the birth of the Bauhaus

Fig. 4. A kitchen unit by Gunnar Asplund at the Home Exhibition, 1917. Note the difference in decoration compared to fig. 1!

Unknown. Gunnar Asplunds förslag till bostadskök, 1917. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 3, 2019. https://digitaltmuseum.org/021107753838/utstallning-anordnad-av-svenska-slojdforeningen-senare-svensk-form-pa-liljevalchs.

The writings of Ellen Key and the image of Lilla Hyttnäs converged in the propaganda piece “Vackrare Vardagsvara” (transl. “More Beautiful Everyday Things”), written by Gregor Paulsson and published by the Swedish Handicraft Association in 1919. The oldest organization of its kind, the Swedish Handicraft Association (Svenska Slöjdföreningen) formed in 1845 as a non-profit organization tasked with promoting Swedish design nationally and internationally. Engaging with this task through different design exhibitions and movements, the SHA hosted the Home Exhibition in 1917, which became the start for Paulsson’s writings. In designing for the exhibition, all artists were prompted with designing with a cost limitation: a single room at max. 260kr, a single room and a kitchen for 600kr, and two rooms and a kitchen for 820kr. (Hedström 2001) The result was a showcase of 23 apartments and their respective interiors: a proof that design could be both affordable and beautiful. (Fig. 4) Extending these ideas, “Vackrare Vardagsvara” demanded that artists ought to work in direct collaboration with factories to produce high-quality everyday objects that could be accessible to everyone.

During the same year that Paulsson appealed for the beautification of everyday things, the Staatliches Bauhaus was founded. Published in April 1919, the Bauhaus manifesto urged for the unity of artists and craftsmen in a call for all artists to “return to the crafts!” (Wingler 1969, 31-33) Considering the similarities in the two manifestos – published in the same year and urging for a unity between arts and craftsmanship – it is quite surprising to consider that they remained largely unknown to each other at the time. Both movements were, however, highly influenced by the Deutscher Werkbund and their propagation for a collaborative enterprise between designers and craftsmen, blending art and industry.

II. THE INTERWAR YEARS: Entanglements of Socialism and Design

Fig. 5. Poster for Stockholm Exhibition 1930, created by architect Sigurd Lewerentz.

Lewerentz, Sigurd. “Stockholmsutställningen 1930 av konstindustri konsthantverk och hemslöjd maj- september."

In Svensk Designhistoria, 110. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010

The Bauhaus Legacy: The Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 and the Birth of Funkis

Fig. 6. A single family-unit a lá Carl Hörvik, exhibited at the Stockholm Exhibition at 1930, similar to the architecture of the Bauhauslers.

Hörvik, Carl. “Villa 40." In Svensk Designhistoria, 112. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010.

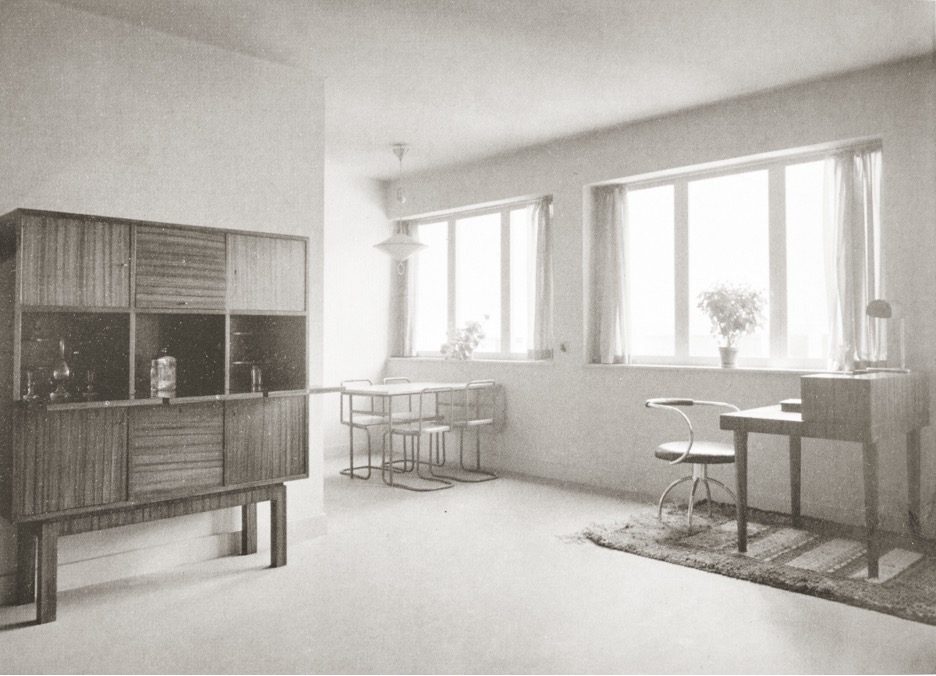

Another exhibition organized by Gregor Paulsson and the SHA, the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 materialized the new vision of modernity and was explicitly envisioned to be a forum of social change. (Murphy 2015, 177) With Paulsson as the main organizer, the exhibition focused on showcasing the “more beautiful everyday thing” and homes and home furnishings laid in the spotlight. Seeking inspiration from the Bauhaus and modernist icons such as France’s Le Corbusier and Russia’s Vladimir Tatlin, Swedish designers aimed to further the vision of modernity and functionalism that was already well-established in other parts of Europe. In many cases, they did so by imitation. The first thing presented to the public, the exhibition poster, had clear connections to the Bauhaus; made by architect Sigurd Lewerentz, painted in the bold color of red, and written in Lewerentz’ own sans serif. (Fig. 5) The dozen buildings showcased were highly similar to those of functionalist architecture as well, with white exteriors, big windows, and flat roofs. (Fig. 6) According to art critic Gotthard Johansson, these looked more like cardboard boxes or shacks rather than the villas and row houses they were aimed to represent. The houses also presented a new vision of interior design, including displays of home furnishings such as silverware, plates, and drinking glasses. These interiors were simple and non-ornamental, and included the introduction of tubular steel furniture, in Erik Lund’s interpretation of the tubular steel experiments taking place at the Bauhaus school in Dessau. (Fig. 7) These were, however, also met with skepticism and seen as too cold and austere to be brought into the home. Criticized by one of Sweden’s top interior designers at the time, Carl Malmsten, the interiors showcased at the exhibition were seen as too doctrinaire and non-traditional, lacking the ‘Swedishness’ that Malmsten deemed necessary for a home. (Brunnström 2010, 110-114) Despite harsh critique, however, the Stockholm Exhibition saw over four million visitors during its four month run, and the new style presented, termed “funkis,” continued to influence Swedish design for decades ahead. (Murphy 2015, 177)

Fig. 7. Interior by Erik Lund, including his interpretation of Marcel Breuers’ tubular steel furniture.

Lund, Erik. “Interiör från Stockholmstutställningen 1930." In Svensk Designhistoria, 112. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010.

Lund, Erik. “Interiör från Stockholmstutställningen 1930." In Svensk Designhistoria, 112. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010.

Becoming Lagom, Becoming Swedish

The critique received at the Stockholm Exhibition wasn’t faced with complete dismissal, either. After all, it didn’t come out of nowhere. Sweden has always had a strong cultural norm of lagom, and in order for funkis to be fully accepted, it had to become lagom, too. Meaning “just right,” or “not too little and not too much,” lagom has prevailed as one of the dominant socialist ideals throughout Swedish history. Seen as the quintessential Swedish word, it is closely linked to the Swedish core value of equality. (Åsbrink 2018, 136-138) All should aim to be lagom – including, of course, design. For funkis to adhere to the concept of lagom, it had to listen to its critique and become less radical, softer, and more Swedish. Over the years to come, funkis was toned down and compensated and developed into a warmer strand of the more radical functionalism found in Western Europe. Blending with the earlier ideas of the good home, found in the Larssons’ Lilla Hyttnäs and Paulsson’s Vackrare Vardagsvara, and strongly connecting to the socialist value of lagom, funkis, at last, became accepted by the public.

The interwar years also saw an increase in both the use and the export of wood. While the export of wood had peaked during the late 1890s – with wood making up 40% of Sweden’s export – it had come to a stop at the outbreak of World War I. After the war ended, in 1918, the demand for Swedish wood soon increased again. In 1920, the export of timber was once again on par with the quotations that had applied before the war. (Björklund 1992, 64) With 70% of Sweden’s landscape consisting of forests, Swedes have always had “a special affinity for trees,” and already in 1893, Prince Eugen of Sweden (1865-1947) declared the Swedish national symbol to be the fir tree. (Facos 1998, 101) With trees already being an important source of pride for the Swedish, the rise in export of timber saw an increase in wooden products being produced by the Swedish state. Still to this day, Sweden is the third biggest provider of timber in the world, and wood is one of the most prominent building materials in designing houses, interiors, and furniture.

The rise of Socialism: Imagining Folkhemmet and the Swedish Welfare State

Fig. 8. Swedish prime minister, and leader of the SDP, Per-Albin Hansson, in front of his funkis style row house in Stockholm.

Arbetarrörelsens Arkiv. “Ålsten." In Folkhemmets Byggande, 15. Uppsala: Svenska Turistföreningen, 1992.

Arbetarrörelsens Arkiv. “Ålsten." In Folkhemmets Byggande, 15. Uppsala: Svenska Turistföreningen, 1992.

The success of funkis can thus be attributed to the new idea of “Swedishness” that was rising at the time. During its crystallization, it came to include a love for the forest, social democratic ideals, and the everlasting impact of lagom – and with the introduction of Folkhemmet, solidified into the often exported Swedish identity of today. Translated as “the People’s Home,” Folkhemmetwas a term coined by Per Albin Hansson – leader of SDP and prime minister of Sweden – in a 1928 radio speech. (Facos 1998, 66) In his famous speech, Hansson used the home as a metaphor for a better organized society:

“We have come so far that we are now able to begin to prepare the big home for the people. The task is to create in it comfort and cheer, to make it cozy and warm, bright and gleaming, and free. The foundation of a home is the feeling of togetherness. The good home does not discriminate against the privileged nor the retired […], it does not look down on another or try to gain advantage at another’s expense. In the good home, the strong don’t plunder the weak. In the good home, consideration, cooperation, and helpfulness prevail.” (Hansson 1928)

Considering the low living standards in Sweden at the time, with cities being immensely dirty and congested due to the rapid urbanization following industrialization, Hansson’s speech was a call for action. In fact, one of the primary concerns of the SDP was the overcrowding of cities and the fast spread of diseases as a consequence of such. With a long history of tuberculosis and the attention for public health and sanitation increasing worldwide, SDP adopted the simple and cheap designs of functionalism as a solution for improving living conditions in an affordable manner. Today, Hansson and Folkhemmet are most known for establishing the Swedish welfare system; but another important, yet often overshadowed, aspect of folkhemmetis that it also became a foundational source of entanglements between Swedish politics and Swedish design.

Folkhemmet became a symbol and a vision for what Sweden currently was and had the potential to be; and as a result, the Swedish design world turned its gaze towards the home and its furnishings, eagerly designing for the Sweden of the future. (Fig. 8)

III. SWEDEN AFTER THE WAR: Realizing Folkhemmet and the foundation of IKEA

The interwar period in Sweden was one of incubation, planting ideas of functionalism and social democracy, and developing a vision of the Swedish future. The years following the second world war, on the other hand, saw a series of concrete changes. During this time, the Swedish economy was booming, and in 1950, Sweden was one of the fastest growing economies in the world.

90 Years of Peaceful Socialist Revolution

Sweden’s steady economic growth, under the lead of the SDP, enabled a social revolution that turned into a haven for social mobility. (Kristoffersson 2015, 76) The idea of the modern Swedish society was founded upon collective successes and the vision of a new Swedish identity; with the emergence of the social welfare system followed a sense of national pride. The SDP, ruling Sweden almost completely uninterruptedly from 1917-1976, worked hard not just to create material security, but also to enable emotional stability and a feeling of belonging amongst the Swedish population. (Larsson och Molander 2019) For the social democrats, the most important thing was to fight class divisions and to level the Swedish population. During their long rule, they implemented several socialist reforms – free education, child benefits, the public unemployment insurance fund, regulations of housing standards, and free public healthcare – that realized a socio-economic security to a greater degree than most other nations. During their rule, the SDP aimed to promote an equality of the highest standards rather than an equality of minimal needs. For housing, this meant no singling out of low-income families and no subsidized housing program being implemented – as was the case in many other nations in Europe. (Rudberg 1992, 26) Instead, everyone was envisioned to live in the same identical housing unit – no matter their social class – and so, Folkhemmet became a reality.

The Materialization of Folkhemmet

Fig. 9. One of the most well-known examples of star house architecture: the ‘Gröndal’ neighborhood in Stockholm,

designed by Leif Reinius and Sven Backström, built during the folkhem era.

Bladh, Oskar. Stjärnhus och terrasshus i Gröndal Exteriör. 1962. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 5, 2019. https://digitaltmuseum.se/011015009396/stjarnhus-och-terrasshus-i-grondal-exterior-flygbild-over-grondal-stjarnhus.

During the post-war years, Folkhemmetmoved from being a metaphorical concept into a reality. Between 1945 and 1960, 900,000 homes were built in Sweden. (Olsfelt 2011) With a focus on the multi-family unit, it was in the materialization of Folkhemmet that the functionalist influences from the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition really started being appropriated and re-imagined. Seeking to improve the highly congested living conditions that had prevailed in Sweden, the new housing focused on providing space and light for all citizens in the folkhem era. The new units were regulated to be big enough to not host more than two people in the same room; a family of four, for example, would have to live in a tenement of two-rooms and a kitchen to not classify as living in a cramped manner. With large areas of Sweden being famously dark and cold for long months of the year, there was also an emphasis on light, and every apartment had to receive some daylight throughout the day. (Thörn 1997, 410) In order to accommodate for these regulations, the star house (stjärnhus) was invented by architects Sven Backström and Leif Reinius. (Larsson och Molander 2019, 19) An apartment complex of three to four floors, the star house was one of the most popular buildings of the folkhem era and can be easily spotted in Swedish cityscapes today. The name of the buildings stem from their form and construction, being a structure of three houses joined together in the shape of a three-pointed star with a common stairwell in the middle. Because of the building’s shape, each apartment in the star house has windows facing in three directions. Each star house could then be connected to other star houses, creating hexagonal structures enclosing a courtyard protected by six walls. (Figure 9) Other popular structures during the folkhem era were row houses and semi-detached houses, which provided sufficient space while being cheap in construction.

Fig. 10. Classic folkhem architecture: the multi-family dwelling with earthy-colored facades and a small courtyard. In Rosta, Örebro.

Nelsäter, Hans. “Rosta, Örebro." In Folkhemmets Byggande, 84. Uppsala: Svenska Turistföreningen, 1992.

In contrast to the buildings that had been shown at the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition, the architecture of Folkhemmet was more playful. Rather than the Bauhaus-inspired buildings – flat-roofed and with white exteriors – the houses of Folkhemmet saw a regression in terms of style, with elements from the era of national romanticism once again being emphasized. The new buildings saw the return of the traditional gable roof and were, despite the survival of the functionalist non-ornamental exterior, more expressive. The new facades were accentuated by balconies and bay windows – which both had functional purposes – and were painted in earthy tones of red, yellow, and green. (Fig. 10) Instead of being purely decorative, the new accentuation had its own purpose and reason for being there, while simultaneously giving the building its own character. (Rudberg 1992, 72-73) Thus, despite becoming more expressive, the architecture of Folkhemmet still remained some of the most important ideals from the functionalism of the 1930s, such that less is more, and that form follows function.

The New Interior

The era of Folkhemmet also generated a new way of living, following the writings of Ellen Key. The new functionalist approach, emphasizing simple and non-decorative forms, was seen as practical and sanitary – and thus, in Key’s writings, beautiful. During the build of Folkhemmet, several housing studies were carried out by the state. Whereas the highly congested way of living was a known fact, the studies revealed that many families in fact chose to live in this way. Instead of spreading out in the home, many families crammed together when time came to sleep, giving rise to the new notion of “voluntary overcrowding.” (Brunnström 2010, 158) One example describes: “the whole family – five people – slept in the compact space of 10.5m2, while double-sized beds in both the living room and kitchen remained unused.” (Brunnström 2010, 158) The studies also revealed that furniture was often chosen on the basis of impressing friends and acquaintances rather than fulfilling a functional purpose within the home, and that parlors were reserved for the sole purpose of hosting guests and parties, remaining unused in the family’s everyday life.

During the post-war years, home furnishing became an issue of public education and several courses in home decoration were offered throughout Sweden. (Kristoffersson 2015, 82) In the new Sweden, everyone ought to know how to utilize their home in a functional manner – and remain good taste in the process – and home decoration became an issue of democracy and civil society.

The 17-Year-Old Businessman: Ingvar Kamprad and his IKEA

A common saying in Sweden is that “Per Albin Hansson built the folkhem, Ingvar Kamprad furnished it.” (Söderholm 2005, 10) As new ideas of home life and home decoration expanded, the need for designs that were accessible to everyone increased. Since the folkhem was meant to house all of Sweden – despite differences in socio-economic class – its interior had to be both tasteful and cheap. In 1946, the state inquired for furniture that could “satisfy the consumer’s needs for good furniture at the lowest possible price.” (Goude et al, 1949) At that, IKEA was born.