Anneli Xie

Profs. Karin Annebäck & Björn Fritz

SASH56: Modern Design in Scandinavia

2019/11/13

Profs. Karin Annebäck & Björn Fritz

SASH56: Modern Design in Scandinavia

2019/11/13

Unifying a Region: The

Promotion of Scandinavian Design through its Relation to Nature

Surrounded by forests, lakes, mountains, and fjords, nature has inevitably

become a central part of Scandinavian culture. Whereas nature permeate many

areas of Scandinavian culture, nature’s biggest admirer may be found

within the Scandinavian design world. Since the end of World War II in 1945, the

unified Scandinavian entity and the concept of “Scandinavian Design” has grown

to become hugely popular. Whereas many of the exported ideas of “Scandinavianess”

are grounded in myths and stereotypes about the region, it has over time been re-interpreted and re-perpetuated by the Scandinavians

themselves. (Halén and Wickman 2003, 103) Although many aspects have contributed to the triumph of

Scandinavian design, one of the unifying factors has been the emphasis of

nature; and in search of an antidote to the cold industrial modernism that had

previously dominated design, a return to the natural became a huge success. (Ashby 2017, 140-141) Through exploring how Scandinavian design depicts natural forms, uses natural

materials, and designs for the ‘natural,’ this paper will examine the different

ways in which nature is integrated into the concept of Scandinavian design, and

how this is made a central theme in the creation and promotion of the identity

of the region.

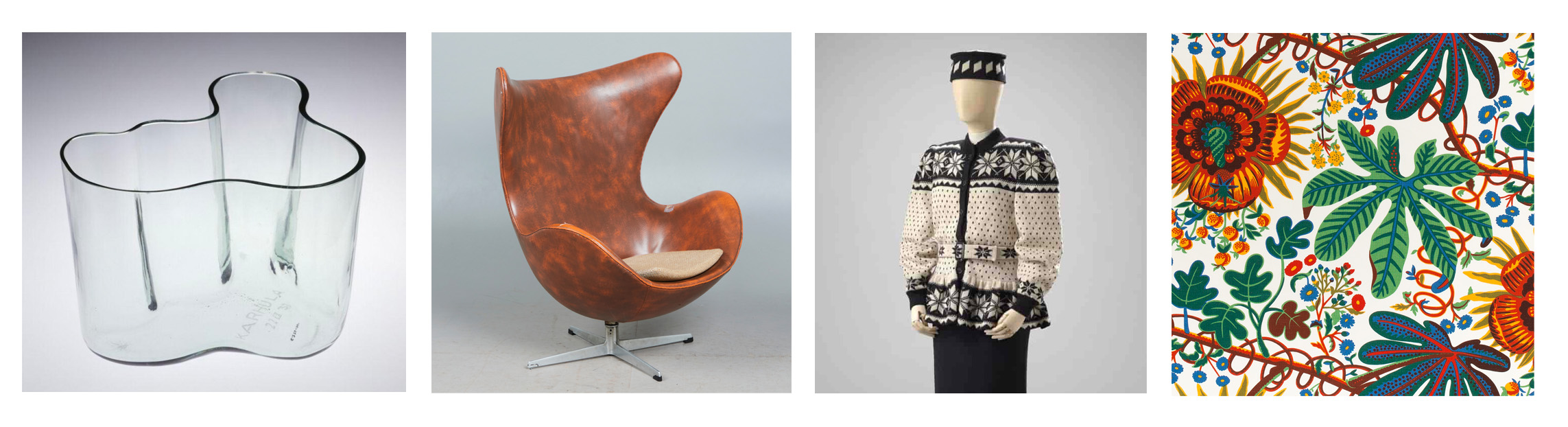

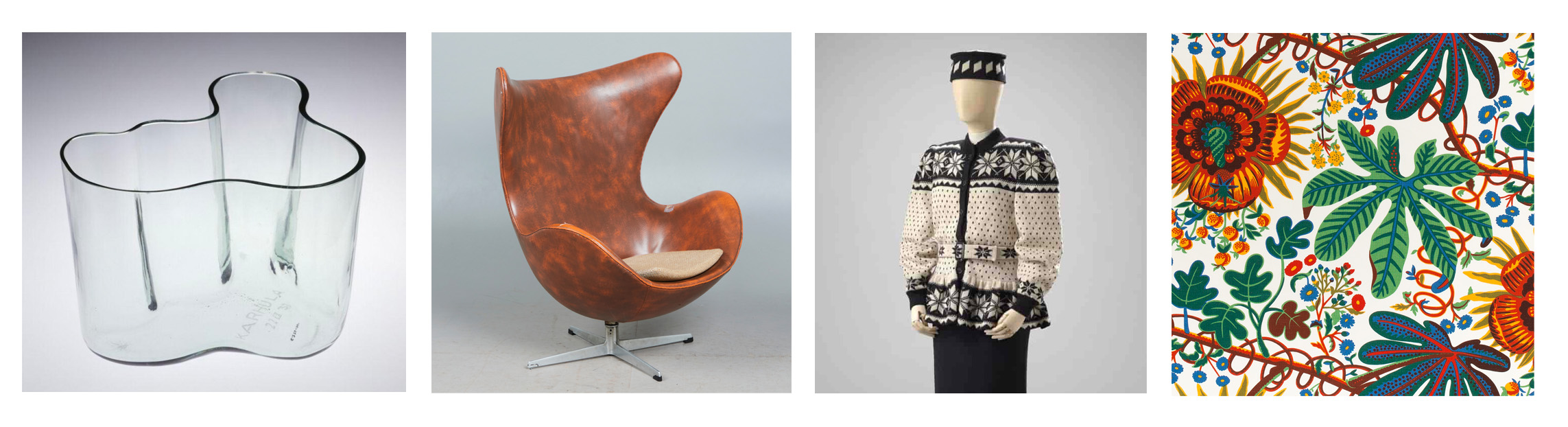

From left to right: Fig. 1: "Aalto Vase" by Alvar Aalto, Fig. 2: "Egg" by Arne Jacobsen,

Fig. 3: "Rosa Heimafrå" by Ellinor Flor, and Fig. 4: "Aralia" by Josef Frank.

Ashby, Charlotte. Modernism in Scandinavia: Art, Architecture and Design. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Brunnström, Lasse. Svensk Designhistoria. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010.

Fiell, Charlotte, and Peter Fiell. Scandinavian Design. Berlin: Taschen, 2002.

Halén, Widar and Kerstin Wickman. Scandinavian Design Beyond the Myth: Fifty Years of Design from the Nordic Countries. Stockholm: Arvinius Förlag, 2003.

The World Bank. “Forest Area (% of land).” Accessed November 7, 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ag.lnd.frst.zs?name_desc=false.

From left to right: Fig. 1: "Aalto Vase" by Alvar Aalto, Fig. 2: "Egg" by Arne Jacobsen,

Fig. 3: "Rosa Heimafrå" by Ellinor Flor, and Fig. 4: "Aralia" by Josef Frank.

Perhaps the most obvious reference to nature in

Scandinavian design is the depiction of natural forms. Finnish designer Alvar

Aalto was known for seeking inspiration in the Finnish lakes, seen in the Aalto

vase (fig. 1), Danish designer Arne Jacobsen, creator of the Ant Chair and the Egg armchair (fig. 2), evidently had an affinity for natural life, the textile designs of Austrian-Swedish designer Josef Frank showcased flowers

and plants intertwined in beautiful textile patterns, (fig. 4) and Norwegian textile artist Ellinor Flor uses snowflakes and flowers in her

“Norse revival […] contemporary fashion.” (fig. 3) (Halén and Wickman 2009, 19) The Scandinavian fondness of nature travelled the world through several

different exhibitions in the post-war years, gaining popularity for the rejection of the sterile modernism of the Bauhaus,

instead proposing a more vulnerable mode of functionalism. Among the objects exhibited, Tapio Wirkkala’s Leaf (fig. 5), showcased at the Milan Triennial in 1951, left a particularly strong imprint.

Crafted from aircraft plywood with laminated veneers and shaped to resemble a leaf, Wirkkala’s platter was deemed “the most

beautiful object of 1951” by the American magazine House Beautiful. (Halén and Wickman 2009, 70) With its international blessing, Leaf and

its natural form became an emblem for Scandinavian design as a whole. In the

following years, the depiction of natural elements in Scandinavian design

became a tool for marketing and promotion of the region by continuously making

the reference to nature pronounced and accessible.

Another well-known theme of nature in Scandinavian design is the use of locally sourced natural materials, with wood being the most prominent one. However, whereas it can be argued that the popularity of depicting natural forms stemmed from a wish of promoting international ideals of Scandinavia, the popularity of wood usage was first and foremost because of its practicality as a cheap and accessible material. With more than 70% of both Finland and Sweden covered by forests, (The World Bank 2019) the dominance of wood is not surprising. Wood has always been a cheap and readily available resource in Scandinavia and has since long been a source of regional pride. Tied to Scandinavian tradition – and encouraged by the Green Wave in the 1960s (Brunnström 2010, 288) – it can thus be seen as fortuitous that wood also fit perfectly into the post-war opposition to Nazism, fascism, and the rise of democratic design by being a modest and unobtrusive material. (Halén and Wickman 2009, 70) The usage of wood can therefore be seen as stimulating a domestic market rather than adapting to an international one; although the two has been known to intertwine as the idealized vision of the Scandinavians were that of peace, warmth, and celebration of tradition; an ideal seen in the material of wood, and a vision well-received in its export to post-war consumers. (Fig. 6)

Finally, Scandinavian design has also become known for designing for the ‘natural state’ by emphasizing comfort and equality, two factors easily identified in the rise of the Scandinavian anti-fashion movement in the 1970s. Aligned with the anti-design movement and the protest movement of 1968, the late 60s and early 70s marked an era of social change, raising questions of overconsumption, gender norms, and climate change – and design became a tool of social critique. (Brunnström 2010, 290) Katja Geiger of Katja of Sweden was a pioneer within the field of women’s liberation, reaching international success by adding the element of comfort to women’s clothing, without eliminating its beauty. Her clothing was designed for the ‘natural’ woman, rid of unrealistic body ideals from the past, representing a new standard of womanhood and modernity. (Brunnström 2010, 264) In 1966, unisex clothing was introduced for the first time; a statement of genderlessness used to oppose norms and promote comfort and functionality. The Swedish fashion line Mah-Jong quickly became a visionary within the field, using bright colors and bold patterns in designing for equality. (Fig 7) In this way, the Scandinavian fashion movement was an emblem of democratic fashion, promoting women as something more than just objects of beauty, bringing them outside of traditional ideals and gender norms.

Designing for the natural state of the human body, the anti-fashion movement was radical, new-thinking, and daring. In comparison to the usage of wood, it was a result of revolution rather than tradition; and compared to the depiction of natural forms, it didn’t have the authorization of the market. Still, despite their differences, all three connections to nature in Scandinavian design ultimately promote the ideals of democracy and equality – unifying and promoting the region as its idealized vision: a utopia of peace, warmth, and social democracy.

Fig. 5. Wirkkala, Tapio. “Leaf,” 1951. Aircraft plywood.

(47×25×3 cm)

Another well-known theme of nature in Scandinavian design is the use of locally sourced natural materials, with wood being the most prominent one. However, whereas it can be argued that the popularity of depicting natural forms stemmed from a wish of promoting international ideals of Scandinavia, the popularity of wood usage was first and foremost because of its practicality as a cheap and accessible material. With more than 70% of both Finland and Sweden covered by forests, (The World Bank 2019) the dominance of wood is not surprising. Wood has always been a cheap and readily available resource in Scandinavia and has since long been a source of regional pride. Tied to Scandinavian tradition – and encouraged by the Green Wave in the 1960s (Brunnström 2010, 288) – it can thus be seen as fortuitous that wood also fit perfectly into the post-war opposition to Nazism, fascism, and the rise of democratic design by being a modest and unobtrusive material. (Halén and Wickman 2009, 70) The usage of wood can therefore be seen as stimulating a domestic market rather than adapting to an international one; although the two has been known to intertwine as the idealized vision of the Scandinavians were that of peace, warmth, and celebration of tradition; an ideal seen in the material of wood, and a vision well-received in its export to post-war consumers. (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6. Mathsson, Bruno and Astrid Sampe. “The gentleman’s room,” 1957.

Finally, Scandinavian design has also become known for designing for the ‘natural state’ by emphasizing comfort and equality, two factors easily identified in the rise of the Scandinavian anti-fashion movement in the 1970s. Aligned with the anti-design movement and the protest movement of 1968, the late 60s and early 70s marked an era of social change, raising questions of overconsumption, gender norms, and climate change – and design became a tool of social critique. (Brunnström 2010, 290) Katja Geiger of Katja of Sweden was a pioneer within the field of women’s liberation, reaching international success by adding the element of comfort to women’s clothing, without eliminating its beauty. Her clothing was designed for the ‘natural’ woman, rid of unrealistic body ideals from the past, representing a new standard of womanhood and modernity. (Brunnström 2010, 264) In 1966, unisex clothing was introduced for the first time; a statement of genderlessness used to oppose norms and promote comfort and functionality. The Swedish fashion line Mah-Jong quickly became a visionary within the field, using bright colors and bold patterns in designing for equality. (Fig 7) In this way, the Scandinavian fashion movement was an emblem of democratic fashion, promoting women as something more than just objects of beauty, bringing them outside of traditional ideals and gender norms.

Fig. 7. Jönsson, Gittan. Front cover of Mah-Jong’s mail order catalog in 1972.

Designing for the natural state of the human body, the anti-fashion movement was radical, new-thinking, and daring. In comparison to the usage of wood, it was a result of revolution rather than tradition; and compared to the depiction of natural forms, it didn’t have the authorization of the market. Still, despite their differences, all three connections to nature in Scandinavian design ultimately promote the ideals of democracy and equality – unifying and promoting the region as its idealized vision: a utopia of peace, warmth, and social democracy.

References

Ashby, Charlotte. Modernism in Scandinavia: Art, Architecture and Design. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Brunnström, Lasse. Svensk Designhistoria. Stockholm: Raster förlag, 2010.

Fiell, Charlotte, and Peter Fiell. Scandinavian Design. Berlin: Taschen, 2002.

Halén, Widar and Kerstin Wickman. Scandinavian Design Beyond the Myth: Fifty Years of Design from the Nordic Countries. Stockholm: Arvinius Förlag, 2003.

The World Bank. “Forest Area (% of land).” Accessed November 7, 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ag.lnd.frst.zs?name_desc=false.