Anneli Xie

Profs. Kimberly Cassibry

ARTH 100: Arts and its Histories

2018/04/16

Profs. Kimberly Cassibry

ARTH 100: Arts and its Histories

2018/04/16

The Subjective Truths and the Politics of Curation:

A Critical Analysis of The Metropolitan Museum of Art and its display of East Asian Landscape Painting

A Critical Analysis of The Metropolitan Museum of Art and its display of East Asian Landscape Painting

Located in the heart of Manhattan,

the Metropolitan Museum of Art has since its establishment in 1872 grown to

become one of the most prominent art museums in the world. Imagining itself as

“a living encyclopedia of world art”, The Metropolitan Museum of

Art, or ‘the Met’ for short, in its mission statement claims it “[...] presents

significant works of art [...] revealing both new ideas and unexpected

connections across time and across cultures.” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) An ambitious statement – but

are they really succeeding? With a collection of over 2 million works of art

spanning 5000 years of world culture, only a small fraction of

the Met’s collection is put on display each year, split among seventeen

curatorial departments divided by 800 galleries across both time and space.

Already taking up nearly two million square feet at the edge of Central Park,

the Met is still limited by space, with most of its collection hidden from

public view, put in storage facilities without having seen light for several

years. (Bradley 2015) Furthermore, even though the curatorial process is long and complex, board

members, trustees, and patrons play a determining role in deciding what

paintings and exhibitions are put on display in the Met’s rotating “Current

Exhibitions” through the financial support they are willing to give to certain

exhibitions. With a museum that “presents significant works of art” and

labels itself as encyclopedic, we as visitors then have to be aware that

patrons have crucial power in deciding what stories get narrated within the

museum since they have influential power in what works get put on display in

the Met’s gallery halls. What artworks are ‘significant’ enough, what stories

are deemed imperative enough to be highlighted – and most importantly, do these

really give us a good and informed picture of the culture and history which

they are representing?

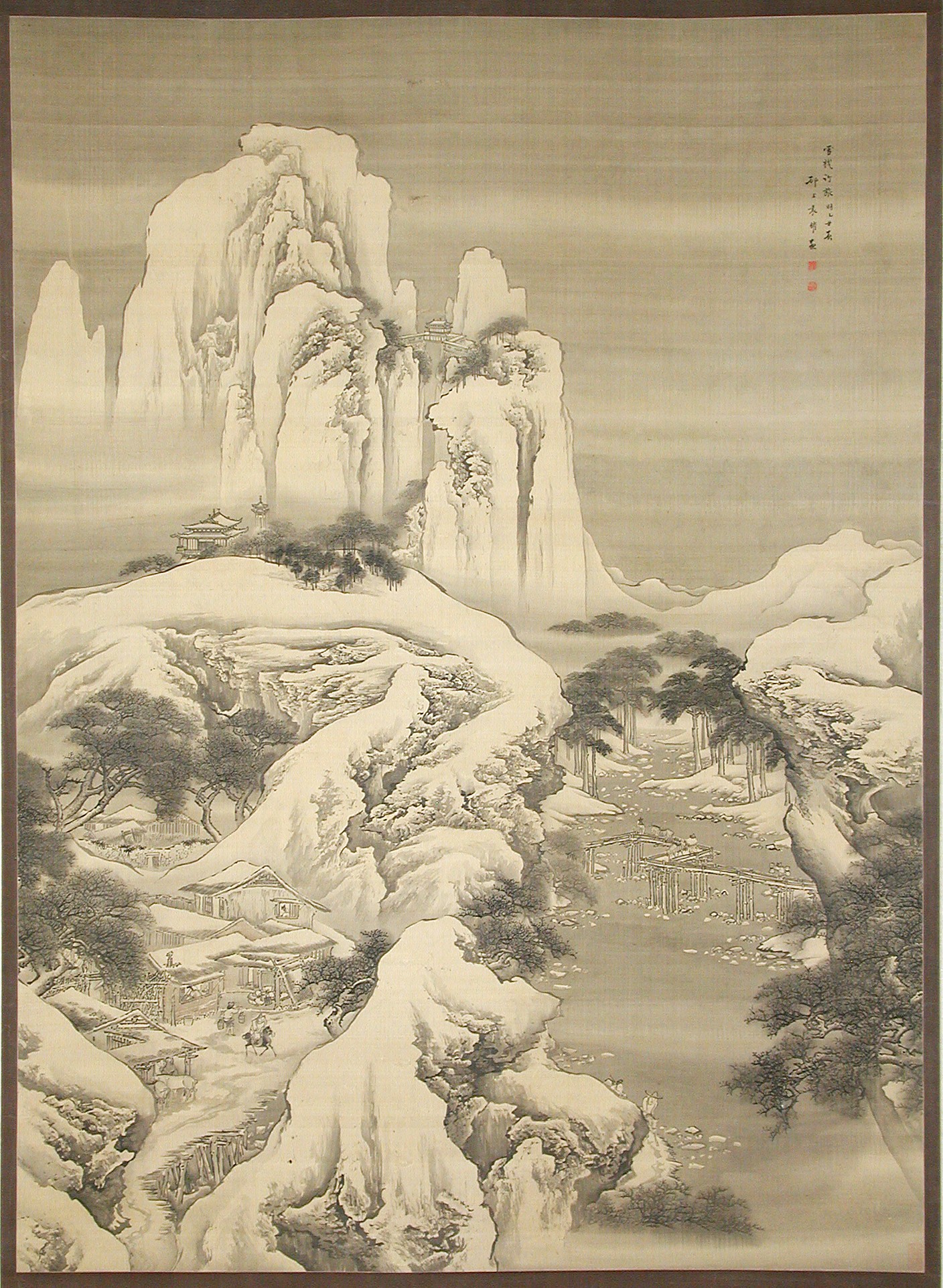

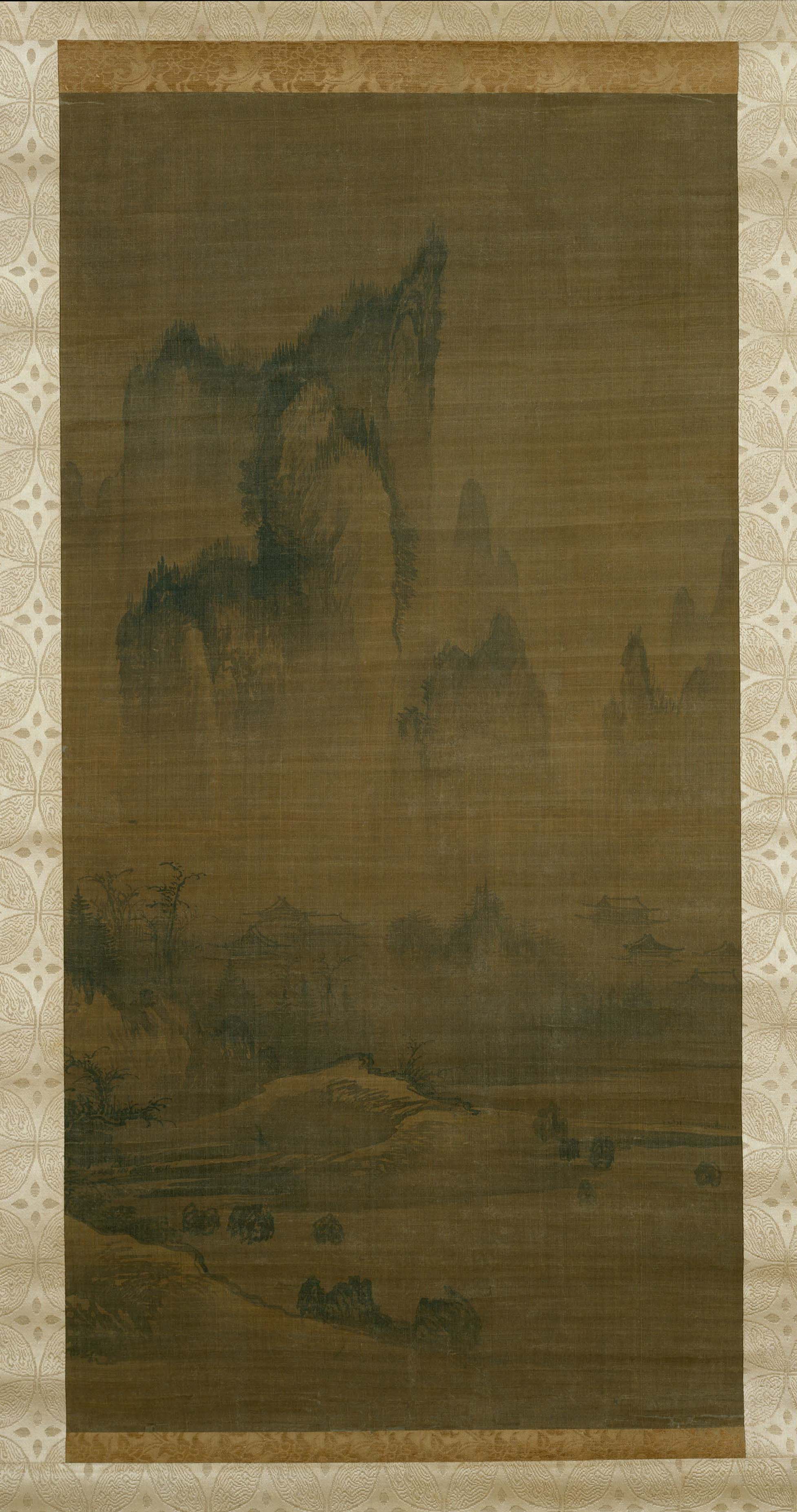

Among the current exhibitions at the Met in April 2018 are two exhibitions on landscape painting in East Asia: “Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China”, funded by Joseph Hotung Fund, on display from August 26, 2017 – August 18, 2019, in galleries 210-216, and “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art”, funded by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea (MCST) and the National Museum of Korea (NMK), on display from February 7 – May 20, 2018, in gallery 233. Delving deeper into both the content and curation of the two exhibitions, it becomes clear that the stories the Met is highlighting lack a big component in their narrative by neglecting a prominent part of intertwined history between the nations, making it fail in its mission of “revealing both new ideas and unexpected connections across times and across cultures.” This essay will explore these claims by looking at the two artworks introducing their respective exhibitions – Yuan Yao’s “Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains” (dated 1745), exhibited as part of “Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China”, on display upon entering the exhibition in gallery 210, and Jeong Seon’s “General View of Inner Geumgang” (dated 1740s), introducing “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art” in gallery 233 – and through analysis of their curation and space within the museum, historical context, as well as application of close formal analysis of the individual works, investigate the politics behind the Met’s display of Chinese and Korean landscape painting.

View of the entry to gallery 210, showcasing the curation of Yuan Yao’s “Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains” (dated 1745).

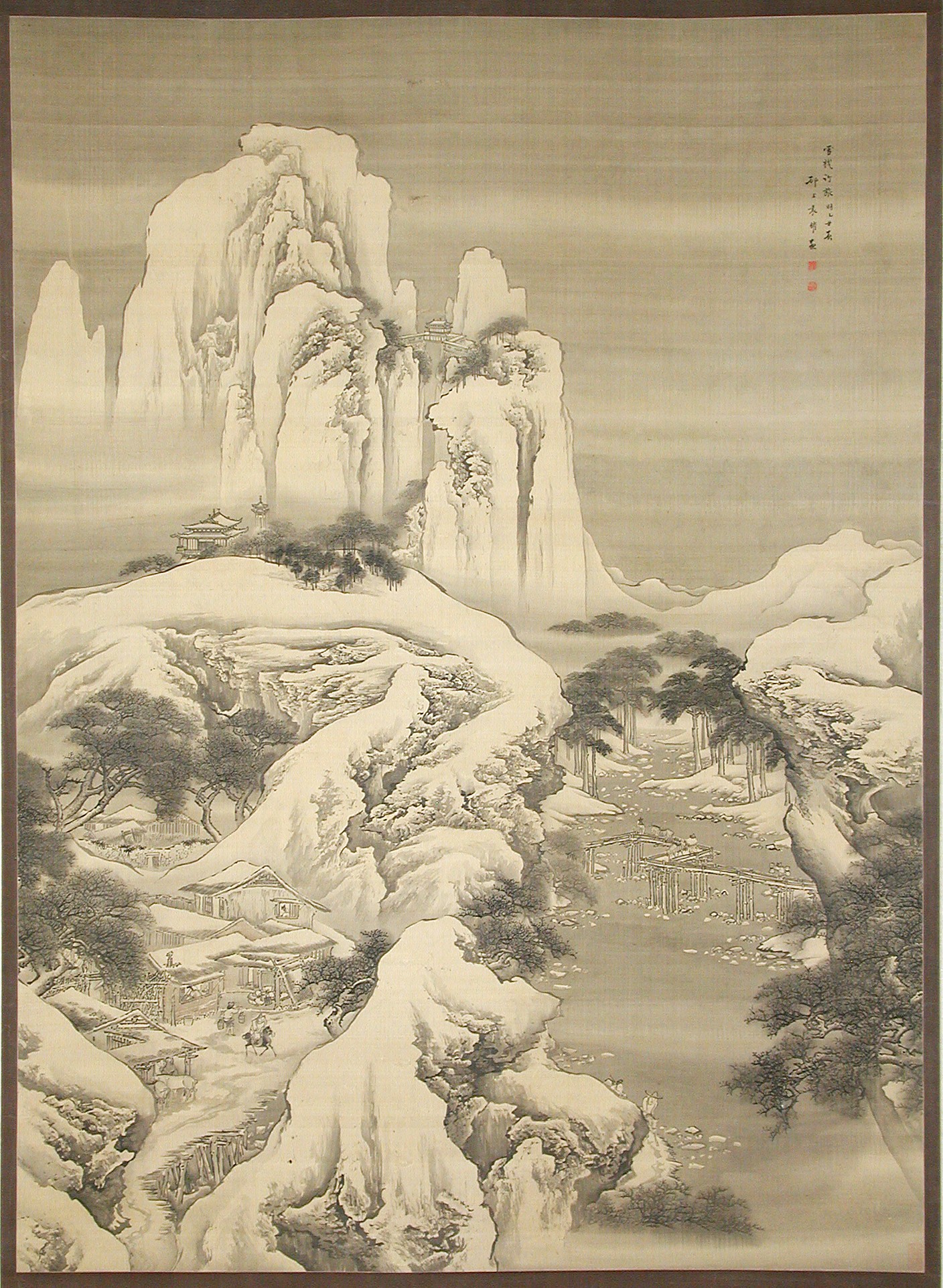

The curation of the two exhibitions contrasts each other in many ways, even though history reveals that the two cultures they are representing, Korea and China, are intimately connected – both physically, having no geographical barriers separating the two – as well as philosophically, influencing and inspiring each other in different ways. Exhibited at the entry of “Streams and Mountains without End”, Yuan Yao’s hanging scroll “Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains” is certainly compelling as it can be glanced upon through the exhibition doors. The hanging scroll, depicting a landscape of mountains and a river, or shánshui (山水画) in Chinese (which directly translates to mountain-water), is painted with ink on silk and takes up a substantial amount of space as it measures 309.2 x 128.3 cm in display. It’s big size makes it a majestic entrance into the dimmed-lit gallery of 210 and its depiction of grand mountains and flowing water makes it a good introduction to shánshui and the world of Chinese landscape painting. Hanging exposed on the wall, the scroll also makes for immersive interaction as it invites its viewers to step close and lose themselves in the scenery – a purpose originally meant to serve the scholars of the Qing Dynasty whom could gaze at the scroll in a courtly setting to fantasize about the ideal society, in which the grandeur of nature reflects the one of man (Banhart 1993, 3-4) – also helped by the lighting in the gallery, creating a dream-like haze. In contrast to the dimmed light of gallery 210, gallery 233 is well-lit; it’s white walls conveying a sense of freshness and modernity, with the first thing visible upon entrance to “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art” also being a more modern painting: “View of Geumgang from Jeongyang Temple”, painted by Lee Ungno in the 1950s, displayed to the right of the exhibition description.

View of the entry to gallery 233, with the exhibition description and Lee Ungno’s “View of Geumgang from Jeongyang Temple”.

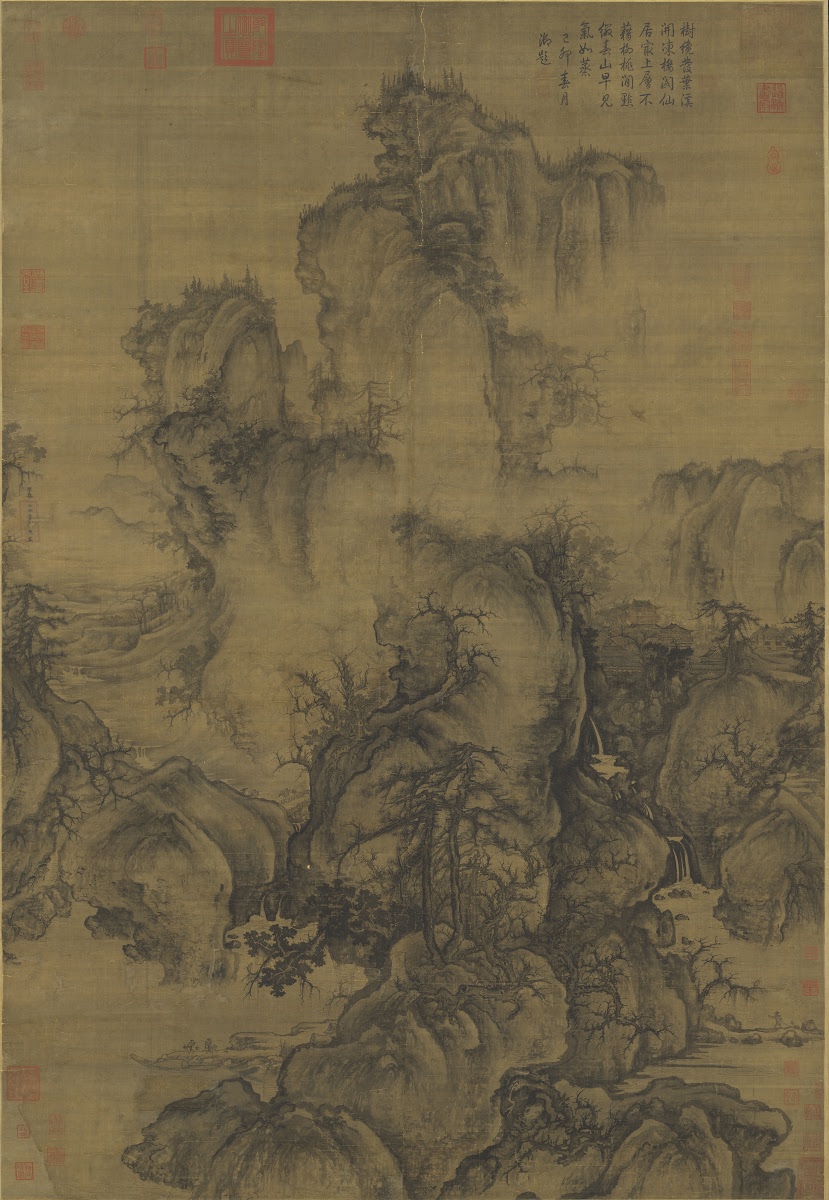

Whereas “Streams and Mountains without End” can be entered from several different galleries (and thus have several different beginnings), the description for “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art” explicitly states that “the exhibition begins to your left”, thus revealing that Ungno’s painting is a visual introduction, yet not a beginning. Instead, the exhibition guides its visitors through linear time, starting in the 18th century with excerpts of Jeong Seon’s “Album of Mount Geumgang” exhibited along the left wall – “General View of Inner Geumgang” being one of them – and continuing to showcase how Jeong’s style has influenced and inspired his successors up until the 21st century. In contrast to the impressive size of Yuan’s hanging scroll, making it possible for the viewer to truly immerse herself in the painted landscape, “General View of Inner Geumgang” is remarkably small in size, measuring 22 × 54.3 cm in its display. With the dimensions of his work, Jeong suggests an intimate experience with his material, in which the viewer can closely observe the scenery. However, in contrast to Yuan, Jeong’s dimensions are indicative of retaining a gaze suspended over the landscape, tracing the mountain peaks, hilltops, and buildings more so as a visiting voyeur, whereas Yuan’s hanging scroll allows for a gaze eventually drowning into its scenery, the viewer entering it to dwell in its fantastical mountains and roaring rivers. The difference of visual experience between the two works make the viewer able to get a sense of the paintings in two completely different ways, with Yuan letting her lose herself within the scenery to become part of it; to feel the scenery for herself, and Jeong letting her hover over to get an impression of the bigger picture and the general view of the mountains, experiencing the landscape first and foremost from his view and perspective. The difference in visual experience make both works suitable as introductory pieces to their respective exhibitions as Chinese landscape painting was initially meant to draw its courtly viewers in and utilize its beauty to daydream about an ideal society, and Korean landscape painting in every way trying to diverge from its neighbors’ idealism, including this, when finding their own voice within the genre – a voice which Jeong very much laid the foundation to. With his works anchoring the exhibition of Korean landscape painting, the curator thus dismisses the history of landscape painting preceding it – much of it finding its roots in Chinese landscape art. By dismissing this part of history, the Met is making a political choice in not affiliating the two neighboring countries, neglecting to communicate the complex history of diplomatic relations between the two.

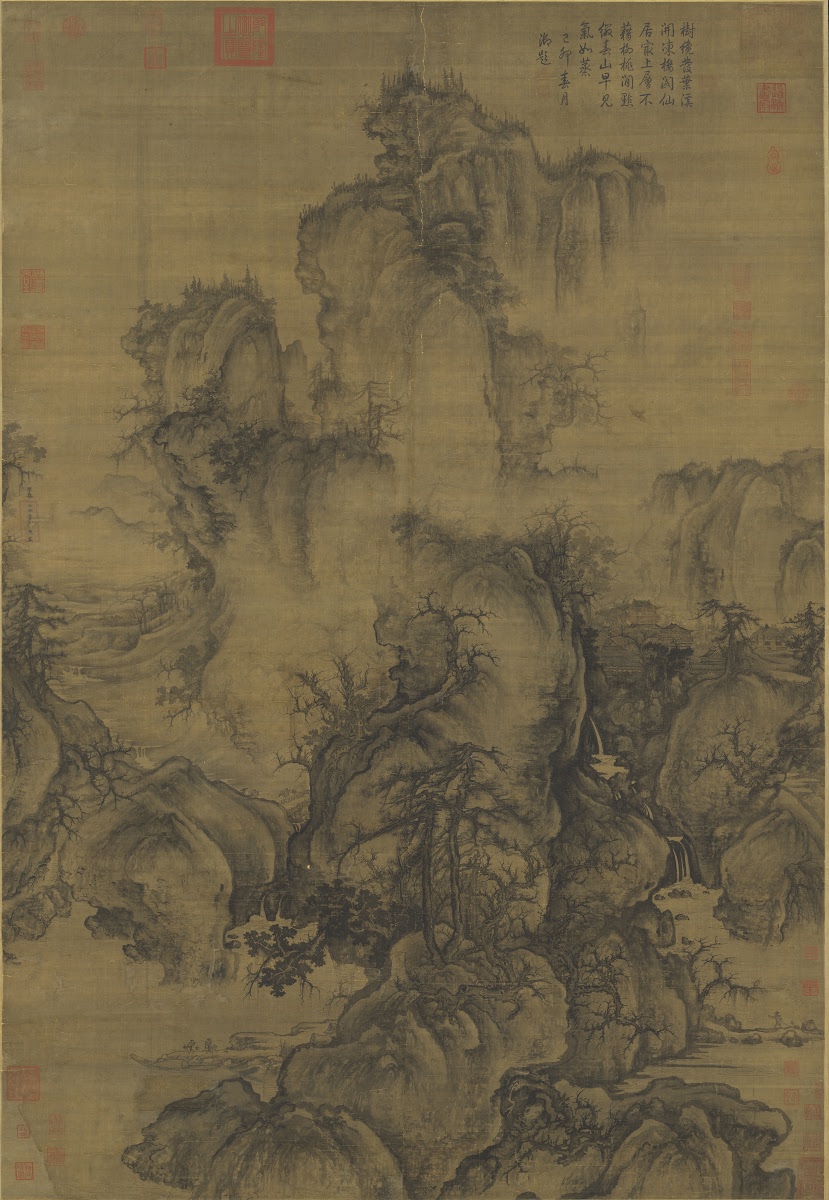

Whereas Yuan Yao has followed Chinese tradition and depicted more of an ideal and a fantasy than an actually existing landscape, Jeong Seon’s work is rooted in naturalism, as he came to pioneer “true-view landscape painting” (jingyeong sansuhw), which revolutionized the genre of landscape painting in the 18th century. (Lee 2018) Yuan Yao, depicting “hostelry and travelers in snowy mountains [in the] spring of the Yichou year [1745...] from the Han River” (Wall label 2018) as the scroll’s inscription reveals to us, affirms his idealism in his composition, following the same traditions that guided the landscape painting that had earlier emerged during the late Tang and early Song period, with great masters such as Guo Xi leading the way. In this tradition, distance and depth was created by dividing the vertical painting into three planes: the foreground, the middle ground, and the background, and held a certain degree of spiritual value influenced by the Neo-Confucian thoughts of li (理) and qi (气), with li referring to the order of nature as reflected in its organic forms (Chan 1969, 248) and qi to the energy, or “vital force forming part of every living thing.” (Yu, Shanli and Peng 2003) Combining the two, no distinction was made between nature and morality, and harmony was believed to exist between the two, as well as between nature and man. (Bush and Shih 2012, 178)

Guo Xi (Chinese, ca. 1000–ca. 1090). 早春圖Early Spring, dated 1072. Chinese, Song dynasty (960-1279). Hanging scroll; ink and light color on silk, 158.3 x 108.1 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Correspondingly, art that was faithful to the world outside the courtly setting, embodying “the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature” was created, and because natural harmony could be seen as a reflection of harmony of man, natural hierarchy was used as a metaphor for communicating ideas of the well-regulated state in their creation. (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2018) Following this thought, the three planes were divided in order to connect man with the grandiosity of nature, with the foreground consisting of earthly bound things such as animals, people, and buildings, the middle ground depicting emptiness in the form of mist, water, or clouds, and the background showcasing heavenly elements such as mountains, hills, and sky. (Bush and Shih 2012, 169) For Yuan, a Chinese scholar, this conceptualized model was important to follow as he under his life in the Qing dynasty lived under Manchurian rule. By reverting to the teachings of old masters, Chinese painters such as Yuan returned to traditional Chinese customs in an attempt to restore the Chinese cultural glory of earlier dynasties. In Yuan’s painting, a village inn, people, animals, as well as a man-made bridge zig-zagging through the river can all be found in the foreground, contrasted towards a set of steep mountains piercing the sky in the background, tied together by the middle ground. In the middle ground, Yuan has depicted a subtle mist rising over the trees in front of the mountains, as well as trees bathing in a sea of clouds with only their tree crowns visible on the right, creating a sense of depth and distance although remaining a flat perspective, following the teachings of the Song master painter Guo Xi – “[...] if it is visible throughout its entirety, it will not appear high. If mists enlock its waist, then it will seem high” (Bush and Shih 2012, 169) – to connect the heavenly realm of the mountains with the earthly people of the village.

Yuan Yao (Chinese, active 1730–after 1778). 清 袁耀 雪棧行旅圖 軸 Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains, dated 1745. Chinese, Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Ink and color on silk, 309.2 x 128.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. C. C. Wang and Family, in memory of Douglas Dillon, 2003.

However, in Yuan’s work, traces of the man-made can be found in other places too, as Yuan has placed buildings and bridges in the mountains as well, although these are cut off by the mist in the middle ground, making the distance between the village in the foreground and the mountains in the background seem distant and unattainable. By making this separation, Yuan makes clear that although he has placed earthly bound objects in the heavenly realm, they are very much a wished-for ideal way of life in which man has reached heaven, rather than something that exists in reality. The brush technique used by Yuan is also indicative of this, his landscape aiming to harmonize the li and qi of nature with those of man; the snow-covered mountains in the background appearing voluminous yet almost featherlike, finding its weight in the nothingness of mist; the sea earning a tranquil from the layers of ink-wash creating subtle differences in nuance; the trees lofty enough to not cover the grandeur of the mountains yet not numerous enough to feel smothering; and the bustling village in with figures all painted in close detail. In this way the work has reached that of the sublime, following the sayings of Guo Xi: “the outward appearances and the inner natures of the objects accord with the properties; [...] all the objects are settled [into their forms] by brush.” (Bush and Shih 2012, 171)

Details from 清 袁耀 雪棧行旅圖 軸 Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains, dated 1745.

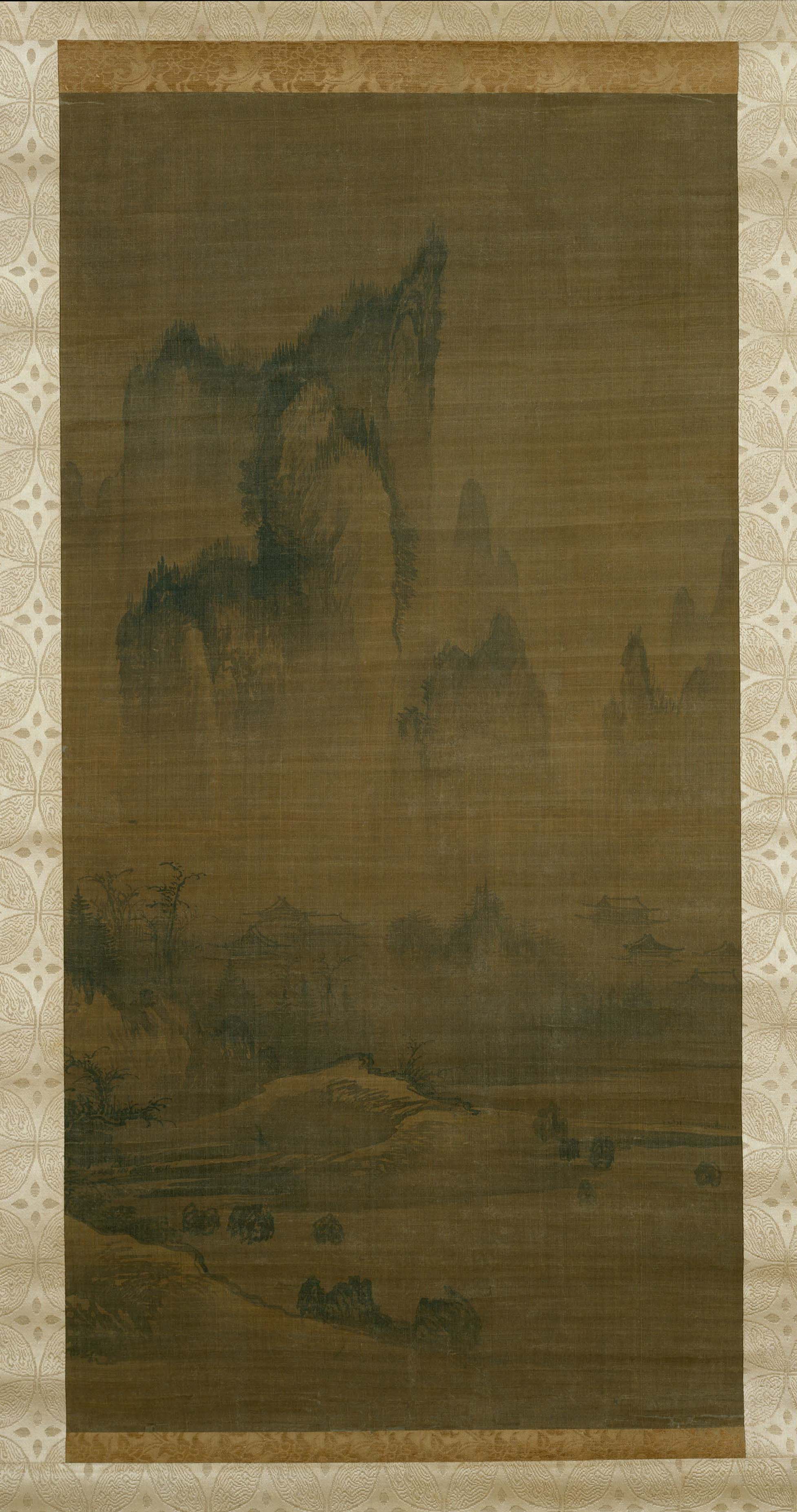

In contrast, Jeong’s painting – originally part of the “Album of Gyeomjae Jeong Seon” – depicts a real landscape – the Diamond Mountains, or Mt. Geumgang, located in today’s North Korea – to which Jeong traveled multiple times. (Hansen 2018) While most Korean landscape artists (Ahn Gyeon and Gang Hui-an, to name two) preceding Jeong drew influences from Chinese masters and depicted conceptual landscapes in accordance to Chinese tradition, Jeong created his own approach. What catalyzed Jeong’s innovative thinking to landscape painting and made him diverge from Chinese traditions must inevitably have been influenced by the 1627 and 1636 Qing invasions of the Joseon dynasty of Korea as well as the 1644 fall of the Ming dynasty of China, to which the Joseon had good diplomatic relations. (Clark 1998, 278) During the period after these events, Korea became increasingly conscious about their own cultural identity, seeking to explore their own heritage rather than drawing inspiration from the fallen Chinese. (Yu 2010)

Style of An Gyeon (Korean, active ca. 1440–1470). Evening bell from mist-shrouded temple, ca. 1450–1500. Korean, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). Pair of hanging scrolls; ink on silk, 78 1/4 x 24 in. (198.8 x 61 cm). Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Mr. and Mrs. Frederick P. Rose and John B. Elliott Gifts, 1987. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY.

For Jeong, this meant incorporating the long-standing tradition of landscape painting into a new way of thinking, thus revolutionizing the genre. Instead of the conceptualized composition utilized by Yuan to depict an ideal connection between man and the heavenly realm, Jeong’s painting, small in scale, is densely packed, illustrating Mt. Geumgang from a birds-eye view. The panoramic composition, unattainable to frame by human eye, suggests that Jeong observed several different parts of the mountains and translated his memories and perception of the landscape into paintings in retrospect. In this way, Jeong was able to assemble each part of the mountains to create a general view and a sense of presence within the landscape as a whole; each part being delicately painted to depict Jeong’s actual perception, unfolding the landscape to fit his own sensation of the scenery – his own true-view of the landscape. “General View of Inner Geumgang” invites the viewer to roam the scenery starting at a path in the bottom right corner, following the East Asian tradition of reading things from right to left. Instead of the monochrome ink-washes and soft brush strokes utilized by Yuan, Jeong has depicted his landscape in a delineated way with short and rapid vertical brushstrokes to depict the mountain peaks like sharp knives piercing the sky, contrasted against short, wet black ink dots painted on washes of vivid green to create a sense of the prosperous growth of the landscape; instead of the blank spaces that Yuan intentionally left in his painting, Jeong has left little room for the mind to roam free by his dense work. Directly opposing Yuan’s lofty and well thought-out harmonious landscape, Jeong’s landscape feels, although slightly more chaotic, also more tangible and realistic. Initially grounded by the path, the viewer’s gaze soon travels through the contrast of the sharp brush strokes depicting the peaks of the mountains and the short black dots on top of mossy greens used to depict tree-covered hills, much like Jeong did himself. Traveling through the landscape, the viewer can also notice several buildings found throughout the painting, presumably in the same places where they were originally observed by the artist himself. In this way, the realism of the true-view landscape might not be reminiscent of the landscape realism that later emerged in the West, but rather integrates the artist’s own interpretation and memory of the landscape depicted. However, in contrast to the tradition of Chinese landscape painting, Korean true-view is actually rooted in real experiences of nature, whereas most Chinese landscape paintings were conceptualized and painted outside of natural experiences.

Jeong Seon (artist name: Gyeomjae) (Korean, 1676–1759). General View of Inner Geumgang; one leaf from the Album of Gyeomjae 謙齋 鄭敾 金剛內山全圖 (謙齋鄭敾畫帖) 朝鮮, ca. 1740s. Korean, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). Album leaf; ink and light color on silk, 13 x 21 3/8 in. (33 x 54.3 cm). Lent by Waegwan Abbey, North Gyeonsang province (National Museum of Korea).

Drawing on formal analysis and history, we can thus see how the two works differ in their approach to the tradition of landscape painting, with Yuan imitating models created by preceding Chinese masters in order to stay true to his own cultural heritage, and Jeong going the opposite direction, diverging from tradition in order to find a Korean identity independent from its neighboring country of China. In the exhibition text to “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art”, the Met reveals that “The Diamond Mountains have come to symbolize a cultural icon so familiarly and powerfully embedded in the national consciousness, and yet so mysterious and just out of reach” (Exhibition Label 2018), and looking at the context behind the creation of Jeong’s work, anchoring the exhibition, this is no surprise. The choice of curating only works succeeding the establishment of Jeong’s true-view landscape, distinct from Chinese traditions, narrates a story of Korea as its own independent nation having its own distinct identity. This isn’t strange considering the rocky relationship China has had with South Korea – establishing diplomatic relations as late as 1992 – and the fact that MCST and NMK, whom are funding the exhibition, are both under South Korean jurisdiction. (Kristof 1992) The choice of art works to be displayed are thus very political since Korea has chosen to completely disassociate from their neighbors, which unfortunately also contradicts Met’s mission of “revealing both new ideas and unexpected connections across times and across cultures,” (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2018) and is a good example of how much power patrons have in the narration of stories the museum tells. By including the history of Chinese tradition in Korea, the Met would have been able to explain why the Diamond Mountains truly became a cultural icon and why they hold such importance, rather than continuing their mystery as full understanding becomes “just out of reach” for the viewer. Instead, their story becomes one-sided to the visitor that has no prior knowledge of the history between the nations, and incomplete to the one who does, serving as an important reminder to always be critical of what story is displayed and narrated as the truth – because in reality, there might be several.

Banhart, Rickard M. Painters of the Great Ming: The Imperial Court and the Zhe School. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 1993.

Bradley, Kimberley. “Why museums hide masterpieces away.” BBC Culture, January 23, 2015. Accessed April 8, 2018. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20150123-7-masterpieces-you-cant-see

Bush, Susan and Hsio-yen Shih. Early Chinese Texts on Painting. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

Chan, Wing-tsit. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Clark, Donald N. “Sino-Korean Tributary Relations under the Ming.” In The Cambridge History of China., Vol. 8 (Jan., 1998): 272-299. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Department of Asian Art. “Landscape Painting in Chinese Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Last modified October, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2018. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/clpg/hd_clpg.htm

Hansen, Sumi. “Diamond Mountains: A Conversation with Curator Soyoung Lee,” Now at the Met, March 15, 2018. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2018/diamond-mountains-curator-conversation

Kristof, Nicholas D. "Chinese and South Koreans Formally Establish Relations," New York Times, August 24, 1992, accessed April 14, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/08/24/world/chinese-and-south-koreans-formally-establish-relations.html.

Lee, Soyoung. Based on original work by Hwi-Joon Ahn. “Mountain and Water: Korean Landscape Painting, 1400–1800.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Last modified October, 2004. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mowa/hd_mowa.htm

Met Publications. “Masterpieces of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Masterpieces_of_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art_1993

Swope, Kenneth M. The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, 1618-44. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “About the Met.”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met

Yu, Hong-june. “True-View Landscape Painting: The Memory of Scenery Extended through the Brush,” Chosun Ilbo, June 5, 2010. Accessed April 11, 2018. http://www.koreafocus.or.kr/design2/layout/content_print.asp?group_id=103107

Among the current exhibitions at the Met in April 2018 are two exhibitions on landscape painting in East Asia: “Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China”, funded by Joseph Hotung Fund, on display from August 26, 2017 – August 18, 2019, in galleries 210-216, and “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art”, funded by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea (MCST) and the National Museum of Korea (NMK), on display from February 7 – May 20, 2018, in gallery 233. Delving deeper into both the content and curation of the two exhibitions, it becomes clear that the stories the Met is highlighting lack a big component in their narrative by neglecting a prominent part of intertwined history between the nations, making it fail in its mission of “revealing both new ideas and unexpected connections across times and across cultures.” This essay will explore these claims by looking at the two artworks introducing their respective exhibitions – Yuan Yao’s “Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains” (dated 1745), exhibited as part of “Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China”, on display upon entering the exhibition in gallery 210, and Jeong Seon’s “General View of Inner Geumgang” (dated 1740s), introducing “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art” in gallery 233 – and through analysis of their curation and space within the museum, historical context, as well as application of close formal analysis of the individual works, investigate the politics behind the Met’s display of Chinese and Korean landscape painting.

View of the entry to gallery 210, showcasing the curation of Yuan Yao’s “Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains” (dated 1745).

The curation of the two exhibitions contrasts each other in many ways, even though history reveals that the two cultures they are representing, Korea and China, are intimately connected – both physically, having no geographical barriers separating the two – as well as philosophically, influencing and inspiring each other in different ways. Exhibited at the entry of “Streams and Mountains without End”, Yuan Yao’s hanging scroll “Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains” is certainly compelling as it can be glanced upon through the exhibition doors. The hanging scroll, depicting a landscape of mountains and a river, or shánshui (山水画) in Chinese (which directly translates to mountain-water), is painted with ink on silk and takes up a substantial amount of space as it measures 309.2 x 128.3 cm in display. It’s big size makes it a majestic entrance into the dimmed-lit gallery of 210 and its depiction of grand mountains and flowing water makes it a good introduction to shánshui and the world of Chinese landscape painting. Hanging exposed on the wall, the scroll also makes for immersive interaction as it invites its viewers to step close and lose themselves in the scenery – a purpose originally meant to serve the scholars of the Qing Dynasty whom could gaze at the scroll in a courtly setting to fantasize about the ideal society, in which the grandeur of nature reflects the one of man (Banhart 1993, 3-4) – also helped by the lighting in the gallery, creating a dream-like haze. In contrast to the dimmed light of gallery 210, gallery 233 is well-lit; it’s white walls conveying a sense of freshness and modernity, with the first thing visible upon entrance to “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art” also being a more modern painting: “View of Geumgang from Jeongyang Temple”, painted by Lee Ungno in the 1950s, displayed to the right of the exhibition description.

View of the entry to gallery 233, with the exhibition description and Lee Ungno’s “View of Geumgang from Jeongyang Temple”.

Whereas “Streams and Mountains without End” can be entered from several different galleries (and thus have several different beginnings), the description for “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art” explicitly states that “the exhibition begins to your left”, thus revealing that Ungno’s painting is a visual introduction, yet not a beginning. Instead, the exhibition guides its visitors through linear time, starting in the 18th century with excerpts of Jeong Seon’s “Album of Mount Geumgang” exhibited along the left wall – “General View of Inner Geumgang” being one of them – and continuing to showcase how Jeong’s style has influenced and inspired his successors up until the 21st century. In contrast to the impressive size of Yuan’s hanging scroll, making it possible for the viewer to truly immerse herself in the painted landscape, “General View of Inner Geumgang” is remarkably small in size, measuring 22 × 54.3 cm in its display. With the dimensions of his work, Jeong suggests an intimate experience with his material, in which the viewer can closely observe the scenery. However, in contrast to Yuan, Jeong’s dimensions are indicative of retaining a gaze suspended over the landscape, tracing the mountain peaks, hilltops, and buildings more so as a visiting voyeur, whereas Yuan’s hanging scroll allows for a gaze eventually drowning into its scenery, the viewer entering it to dwell in its fantastical mountains and roaring rivers. The difference of visual experience between the two works make the viewer able to get a sense of the paintings in two completely different ways, with Yuan letting her lose herself within the scenery to become part of it; to feel the scenery for herself, and Jeong letting her hover over to get an impression of the bigger picture and the general view of the mountains, experiencing the landscape first and foremost from his view and perspective. The difference in visual experience make both works suitable as introductory pieces to their respective exhibitions as Chinese landscape painting was initially meant to draw its courtly viewers in and utilize its beauty to daydream about an ideal society, and Korean landscape painting in every way trying to diverge from its neighbors’ idealism, including this, when finding their own voice within the genre – a voice which Jeong very much laid the foundation to. With his works anchoring the exhibition of Korean landscape painting, the curator thus dismisses the history of landscape painting preceding it – much of it finding its roots in Chinese landscape art. By dismissing this part of history, the Met is making a political choice in not affiliating the two neighboring countries, neglecting to communicate the complex history of diplomatic relations between the two.

Whereas Yuan Yao has followed Chinese tradition and depicted more of an ideal and a fantasy than an actually existing landscape, Jeong Seon’s work is rooted in naturalism, as he came to pioneer “true-view landscape painting” (jingyeong sansuhw), which revolutionized the genre of landscape painting in the 18th century. (Lee 2018) Yuan Yao, depicting “hostelry and travelers in snowy mountains [in the] spring of the Yichou year [1745...] from the Han River” (Wall label 2018) as the scroll’s inscription reveals to us, affirms his idealism in his composition, following the same traditions that guided the landscape painting that had earlier emerged during the late Tang and early Song period, with great masters such as Guo Xi leading the way. In this tradition, distance and depth was created by dividing the vertical painting into three planes: the foreground, the middle ground, and the background, and held a certain degree of spiritual value influenced by the Neo-Confucian thoughts of li (理) and qi (气), with li referring to the order of nature as reflected in its organic forms (Chan 1969, 248) and qi to the energy, or “vital force forming part of every living thing.” (Yu, Shanli and Peng 2003) Combining the two, no distinction was made between nature and morality, and harmony was believed to exist between the two, as well as between nature and man. (Bush and Shih 2012, 178)

Guo Xi (Chinese, ca. 1000–ca. 1090). 早春圖Early Spring, dated 1072. Chinese, Song dynasty (960-1279). Hanging scroll; ink and light color on silk, 158.3 x 108.1 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Correspondingly, art that was faithful to the world outside the courtly setting, embodying “the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature” was created, and because natural harmony could be seen as a reflection of harmony of man, natural hierarchy was used as a metaphor for communicating ideas of the well-regulated state in their creation. (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2018) Following this thought, the three planes were divided in order to connect man with the grandiosity of nature, with the foreground consisting of earthly bound things such as animals, people, and buildings, the middle ground depicting emptiness in the form of mist, water, or clouds, and the background showcasing heavenly elements such as mountains, hills, and sky. (Bush and Shih 2012, 169) For Yuan, a Chinese scholar, this conceptualized model was important to follow as he under his life in the Qing dynasty lived under Manchurian rule. By reverting to the teachings of old masters, Chinese painters such as Yuan returned to traditional Chinese customs in an attempt to restore the Chinese cultural glory of earlier dynasties. In Yuan’s painting, a village inn, people, animals, as well as a man-made bridge zig-zagging through the river can all be found in the foreground, contrasted towards a set of steep mountains piercing the sky in the background, tied together by the middle ground. In the middle ground, Yuan has depicted a subtle mist rising over the trees in front of the mountains, as well as trees bathing in a sea of clouds with only their tree crowns visible on the right, creating a sense of depth and distance although remaining a flat perspective, following the teachings of the Song master painter Guo Xi – “[...] if it is visible throughout its entirety, it will not appear high. If mists enlock its waist, then it will seem high” (Bush and Shih 2012, 169) – to connect the heavenly realm of the mountains with the earthly people of the village.

Yuan Yao (Chinese, active 1730–after 1778). 清 袁耀 雪棧行旅圖 軸 Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains, dated 1745. Chinese, Qing dynasty (1644-1911). Ink and color on silk, 309.2 x 128.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. C. C. Wang and Family, in memory of Douglas Dillon, 2003.

However, in Yuan’s work, traces of the man-made can be found in other places too, as Yuan has placed buildings and bridges in the mountains as well, although these are cut off by the mist in the middle ground, making the distance between the village in the foreground and the mountains in the background seem distant and unattainable. By making this separation, Yuan makes clear that although he has placed earthly bound objects in the heavenly realm, they are very much a wished-for ideal way of life in which man has reached heaven, rather than something that exists in reality. The brush technique used by Yuan is also indicative of this, his landscape aiming to harmonize the li and qi of nature with those of man; the snow-covered mountains in the background appearing voluminous yet almost featherlike, finding its weight in the nothingness of mist; the sea earning a tranquil from the layers of ink-wash creating subtle differences in nuance; the trees lofty enough to not cover the grandeur of the mountains yet not numerous enough to feel smothering; and the bustling village in with figures all painted in close detail. In this way the work has reached that of the sublime, following the sayings of Guo Xi: “the outward appearances and the inner natures of the objects accord with the properties; [...] all the objects are settled [into their forms] by brush.” (Bush and Shih 2012, 171)

Details from 清 袁耀 雪棧行旅圖 軸 Inn and Travelers in Snowy Mountains, dated 1745.

In contrast, Jeong’s painting – originally part of the “Album of Gyeomjae Jeong Seon” – depicts a real landscape – the Diamond Mountains, or Mt. Geumgang, located in today’s North Korea – to which Jeong traveled multiple times. (Hansen 2018) While most Korean landscape artists (Ahn Gyeon and Gang Hui-an, to name two) preceding Jeong drew influences from Chinese masters and depicted conceptual landscapes in accordance to Chinese tradition, Jeong created his own approach. What catalyzed Jeong’s innovative thinking to landscape painting and made him diverge from Chinese traditions must inevitably have been influenced by the 1627 and 1636 Qing invasions of the Joseon dynasty of Korea as well as the 1644 fall of the Ming dynasty of China, to which the Joseon had good diplomatic relations. (Clark 1998, 278) During the period after these events, Korea became increasingly conscious about their own cultural identity, seeking to explore their own heritage rather than drawing inspiration from the fallen Chinese. (Yu 2010)

Style of An Gyeon (Korean, active ca. 1440–1470). Evening bell from mist-shrouded temple, ca. 1450–1500. Korean, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). Pair of hanging scrolls; ink on silk, 78 1/4 x 24 in. (198.8 x 61 cm). Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and Mr. and Mrs. Frederick P. Rose and John B. Elliott Gifts, 1987. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY.

For Jeong, this meant incorporating the long-standing tradition of landscape painting into a new way of thinking, thus revolutionizing the genre. Instead of the conceptualized composition utilized by Yuan to depict an ideal connection between man and the heavenly realm, Jeong’s painting, small in scale, is densely packed, illustrating Mt. Geumgang from a birds-eye view. The panoramic composition, unattainable to frame by human eye, suggests that Jeong observed several different parts of the mountains and translated his memories and perception of the landscape into paintings in retrospect. In this way, Jeong was able to assemble each part of the mountains to create a general view and a sense of presence within the landscape as a whole; each part being delicately painted to depict Jeong’s actual perception, unfolding the landscape to fit his own sensation of the scenery – his own true-view of the landscape. “General View of Inner Geumgang” invites the viewer to roam the scenery starting at a path in the bottom right corner, following the East Asian tradition of reading things from right to left. Instead of the monochrome ink-washes and soft brush strokes utilized by Yuan, Jeong has depicted his landscape in a delineated way with short and rapid vertical brushstrokes to depict the mountain peaks like sharp knives piercing the sky, contrasted against short, wet black ink dots painted on washes of vivid green to create a sense of the prosperous growth of the landscape; instead of the blank spaces that Yuan intentionally left in his painting, Jeong has left little room for the mind to roam free by his dense work. Directly opposing Yuan’s lofty and well thought-out harmonious landscape, Jeong’s landscape feels, although slightly more chaotic, also more tangible and realistic. Initially grounded by the path, the viewer’s gaze soon travels through the contrast of the sharp brush strokes depicting the peaks of the mountains and the short black dots on top of mossy greens used to depict tree-covered hills, much like Jeong did himself. Traveling through the landscape, the viewer can also notice several buildings found throughout the painting, presumably in the same places where they were originally observed by the artist himself. In this way, the realism of the true-view landscape might not be reminiscent of the landscape realism that later emerged in the West, but rather integrates the artist’s own interpretation and memory of the landscape depicted. However, in contrast to the tradition of Chinese landscape painting, Korean true-view is actually rooted in real experiences of nature, whereas most Chinese landscape paintings were conceptualized and painted outside of natural experiences.

Jeong Seon (artist name: Gyeomjae) (Korean, 1676–1759). General View of Inner Geumgang; one leaf from the Album of Gyeomjae 謙齋 鄭敾 金剛內山全圖 (謙齋鄭敾畫帖) 朝鮮, ca. 1740s. Korean, Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). Album leaf; ink and light color on silk, 13 x 21 3/8 in. (33 x 54.3 cm). Lent by Waegwan Abbey, North Gyeonsang province (National Museum of Korea).

Drawing on formal analysis and history, we can thus see how the two works differ in their approach to the tradition of landscape painting, with Yuan imitating models created by preceding Chinese masters in order to stay true to his own cultural heritage, and Jeong going the opposite direction, diverging from tradition in order to find a Korean identity independent from its neighboring country of China. In the exhibition text to “Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art”, the Met reveals that “The Diamond Mountains have come to symbolize a cultural icon so familiarly and powerfully embedded in the national consciousness, and yet so mysterious and just out of reach” (Exhibition Label 2018), and looking at the context behind the creation of Jeong’s work, anchoring the exhibition, this is no surprise. The choice of curating only works succeeding the establishment of Jeong’s true-view landscape, distinct from Chinese traditions, narrates a story of Korea as its own independent nation having its own distinct identity. This isn’t strange considering the rocky relationship China has had with South Korea – establishing diplomatic relations as late as 1992 – and the fact that MCST and NMK, whom are funding the exhibition, are both under South Korean jurisdiction. (Kristof 1992) The choice of art works to be displayed are thus very political since Korea has chosen to completely disassociate from their neighbors, which unfortunately also contradicts Met’s mission of “revealing both new ideas and unexpected connections across times and across cultures,” (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2018) and is a good example of how much power patrons have in the narration of stories the museum tells. By including the history of Chinese tradition in Korea, the Met would have been able to explain why the Diamond Mountains truly became a cultural icon and why they hold such importance, rather than continuing their mystery as full understanding becomes “just out of reach” for the viewer. Instead, their story becomes one-sided to the visitor that has no prior knowledge of the history between the nations, and incomplete to the one who does, serving as an important reminder to always be critical of what story is displayed and narrated as the truth – because in reality, there might be several.

References

Banhart, Rickard M. Painters of the Great Ming: The Imperial Court and the Zhe School. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 1993.

Bradley, Kimberley. “Why museums hide masterpieces away.” BBC Culture, January 23, 2015. Accessed April 8, 2018. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20150123-7-masterpieces-you-cant-see

Bush, Susan and Hsio-yen Shih. Early Chinese Texts on Painting. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

Chan, Wing-tsit. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Clark, Donald N. “Sino-Korean Tributary Relations under the Ming.” In The Cambridge History of China., Vol. 8 (Jan., 1998): 272-299. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Department of Asian Art. “Landscape Painting in Chinese Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Last modified October, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2018. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/clpg/hd_clpg.htm

Hansen, Sumi. “Diamond Mountains: A Conversation with Curator Soyoung Lee,” Now at the Met, March 15, 2018. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2018/diamond-mountains-curator-conversation

Kristof, Nicholas D. "Chinese and South Koreans Formally Establish Relations," New York Times, August 24, 1992, accessed April 14, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/08/24/world/chinese-and-south-koreans-formally-establish-relations.html.

Lee, Soyoung. Based on original work by Hwi-Joon Ahn. “Mountain and Water: Korean Landscape Painting, 1400–1800.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Last modified October, 2004. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mowa/hd_mowa.htm

Met Publications. “Masterpieces of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Masterpieces_of_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art_1993

Swope, Kenneth M. The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, 1618-44. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “About the Met.”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met

Yu, Hong-june. “True-View Landscape Painting: The Memory of Scenery Extended through the Brush,” Chosun Ilbo, June 5, 2010. Accessed April 11, 2018. http://www.koreafocus.or.kr/design2/layout/content_print.asp?group_id=103107