Anneli Xie

Prof. Alice Friedman

ARTH 321: Gender, Sexuality, and the Design of Houses

2020/05/15

Prof. Alice Friedman

ARTH 321: Gender, Sexuality, and the Design of Houses

2020/05/15

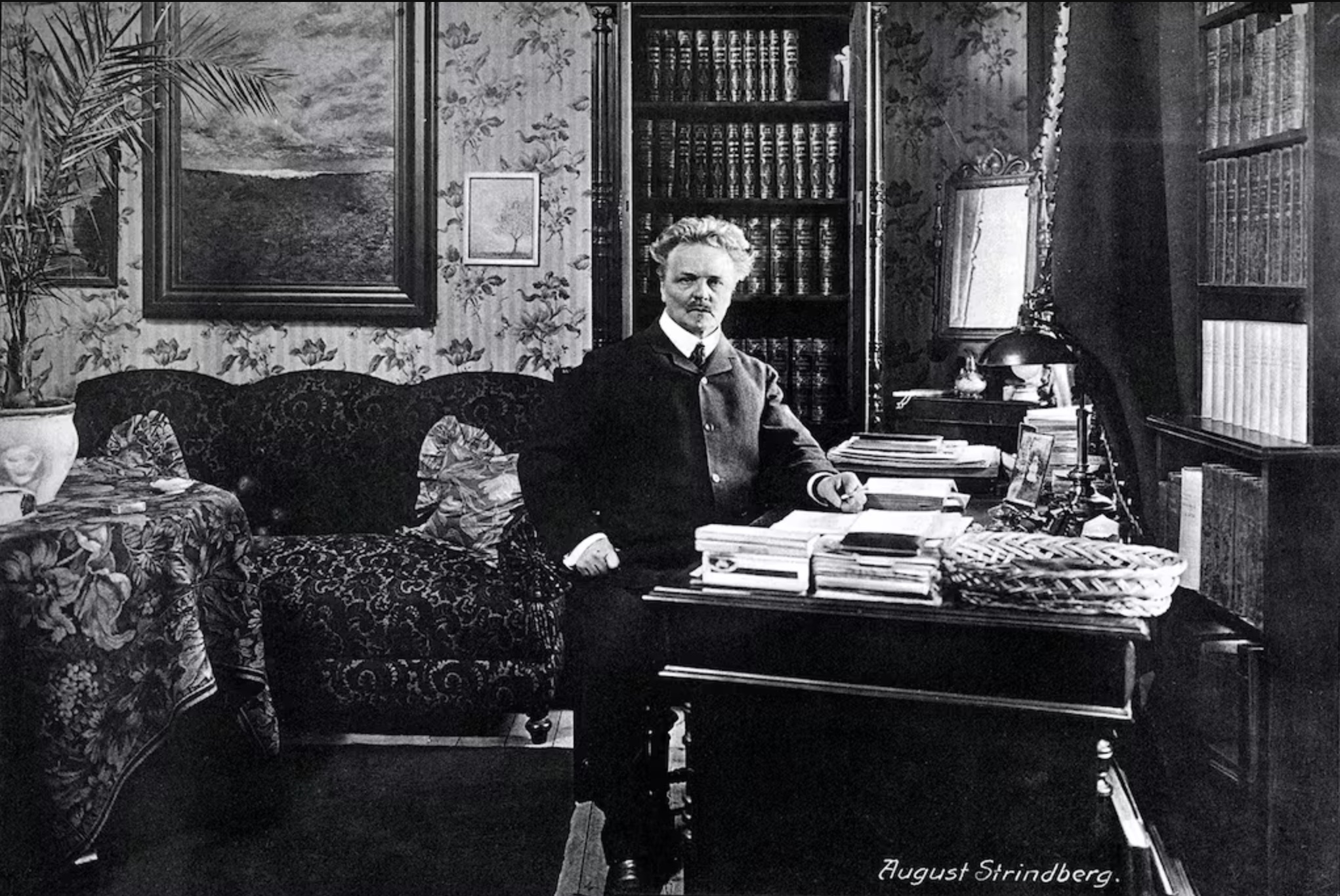

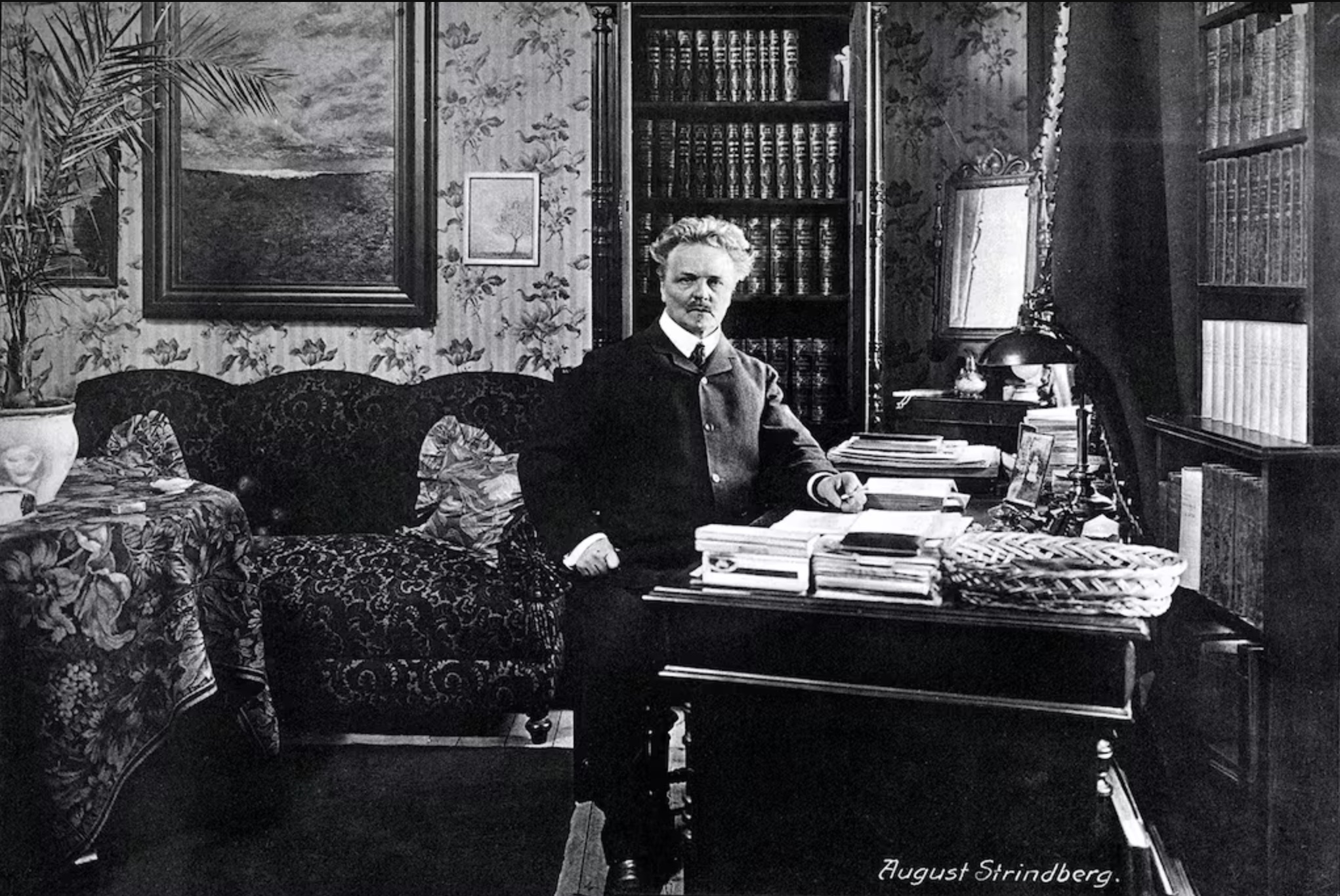

Ellen Key and her Strand: To Not be Forgotten

Ellen Key – alluring writer,

radical thinker, difference feminist, and design revolutionary – is one of

Sweden’s most important scholars. Active at the turn of the 20th

century, Ellen Key and her writings on women’s liberation, children’s

education, love and marriage, and design, were vigorously debated in the public

sphere. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 9) Despite this, the name “Ellen Key” remains widely unknown to the modern Swedish

audience. Eagerly erased by the masculine narrative of the time, Ellen Key is

often rejected from the Swedish history books in the classrooms which she

helped form, as well as excluded from the narrative of Swedish design in which

her ideas are perhaps most prevalent today. Whereas there are many possible

explanations for this, one is inevitably that Key wrote radical essays and

controversial texts rather than engaging in fiction-writing, something that the

more famous writers of her time, such as Selma Lagerlöf and August Strindberg, were

pre-occupied with, making Key’s writings less accessible to the general public.

But Key was also a woman – and not a woman, like Lagerlöf, who wrote fiction –

but a woman who dared to publicly and ferociously criticize the society and the

cultural norms in which she lived within, something that wasn’t easily accepted

at her time. By her male counterparts, Key was often called “hysterical” and

“contradictory;” she was a woman and thought like a woman, meaning

illogically and irrelevantly. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 9) Yet, her ideas were clearly influential enough to attempt to eagerly get rid

of, but to no avail. Still today – almost 100 years after her death in

1926 – many of Key’s ideas still permeate the public debate in Sweden, enduring

because of their continued relevance to the nation’s inherent cultural values.

Who was this authoritative woman and how can we understand her continued

influence, importance, and inspiration on modern-day Swedish cultural values?

This essay will relate Ellen Key’s ideas on women’s place within the home and

design, to her own home, Strand. Strand will act as a case study for discussion

of the home as a place of experimentation, a complex navigation between the

public and the private sphere, and as a personal sanctuary. Under this

scrutiny, an argument will be made that Ellen Key – enigmatic and

multifaceted – is indeed an important historical figure that deserves to

be included in the intellectual, cultural, and historical knowledge of the

ordinary Swede.

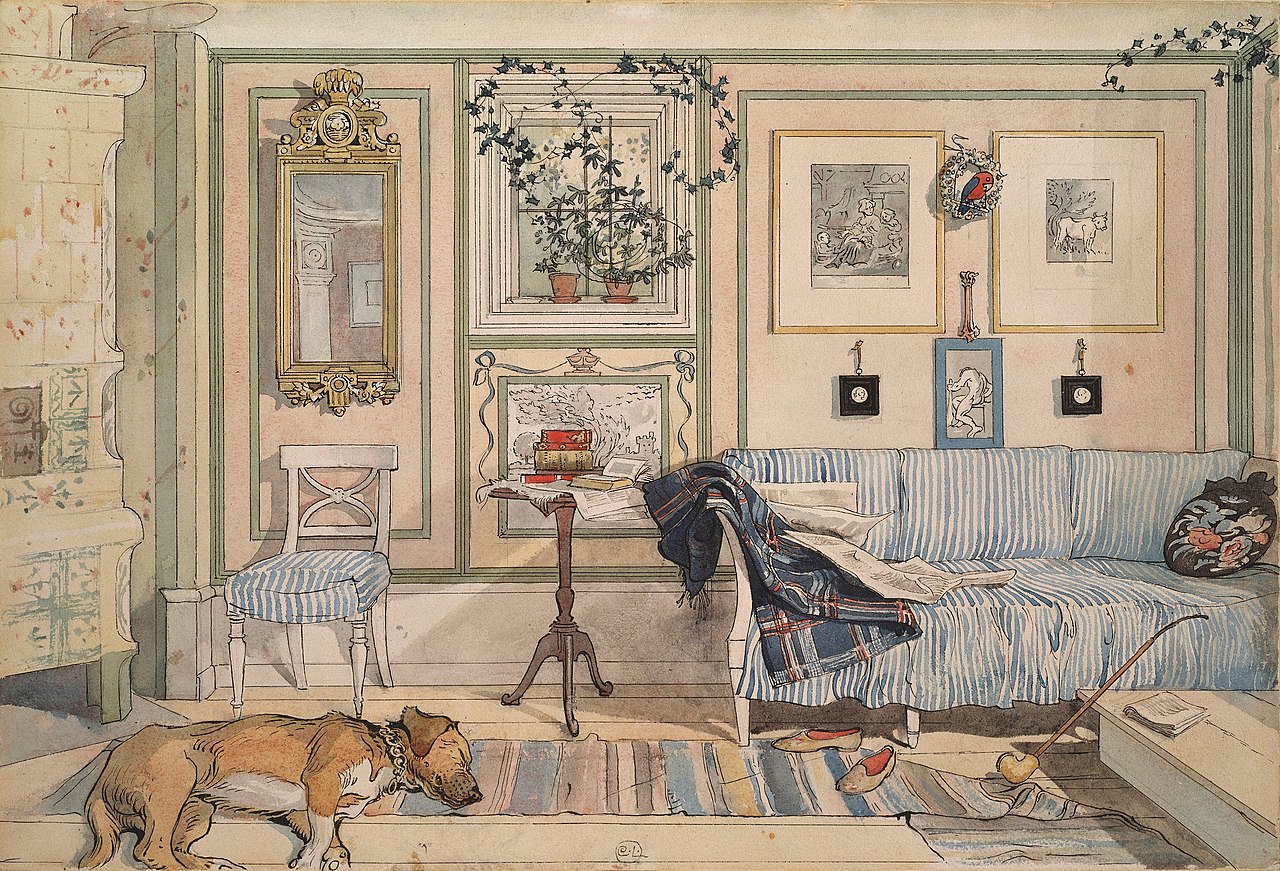

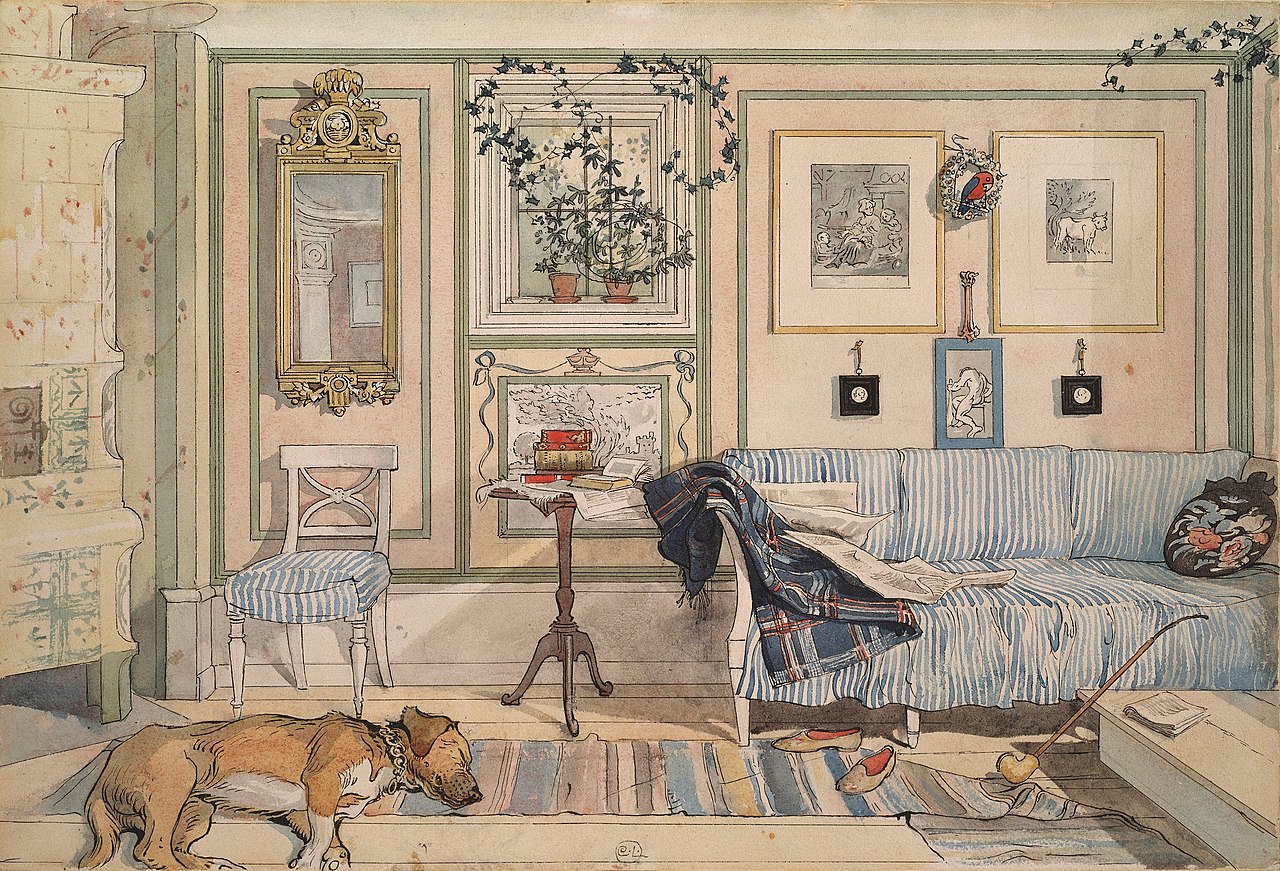

Whereas Ellen Key grew up with a right-wing politician as her father, she eventually started sympathizing with the rising movement of social democracy that developed in Sweden during the late 1880s. (Hellström Sveningson 2011, 44-45) The social democratic ideals of egalitarianism became central to Key’s work, and in 1883, Key joined the left liberalist student association Verdandi, with many of Sweden’s cultural elite, such as Gustaf af Geijerstam, Mauritz Hellberg, and Hjalmar Branting, already being members. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 172) Verdandi advocated for freedom of speech and published Verdandis Småskrifter (transl.: Verdandi’s Journals) in which Ellen Key reached the most success as a writer. In 1899, Verdandis Småskrifter published Key’s essays on beauty within the home in a four-series collection called Skönhet för Alla, (transl.: Beauty for All), which compiled into Key’s aesthetic manifesto. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 436) Inspired by John Ruskin and William Morris’ Arts and Crafts movement in the United Kingdom, Beauty for All directly opposed the low-quality mass-produced goods of industrialization, advocating instead for a return of romanticism, traditional craftsmanship, and folk-style decoration. In Sweden, the influences of the Arts and Crafts movement could be most prominently seen in Lilla Hyttnäs, the Sundborn home of artists Carl and Karin Larsson, which Key praised in her essay as a home that had used “simple means [to reach] the most homely and personal impression.” (Key 1889, 14) Lilla Hyttnäs was an artistic statement: an egalitarian aesthetic in which the handmade coexisted comfortably within the home. Designed entirely by the two Larsson’s, the home was a bold opposition to the dominant design influences in Sweden at the time. It opposed both the decorative neo-renaissance by being characterized by light, simple, and lofty interiors, as well as the industrial mass-production, by being completely handmade: Carl designed the furniture, and Karin wove and knitted various tapestries and textiles. The home was later captured in Carl Larsson’s 1899 book, A Home, which contained 24 watercolor paintings of intimate scenes from the Larsson’s everyday life; the book revolutionized the way Swedes conceived home life and home decoration by introducing the simple concept of domestic informality and comfort. (Söderholm 2005, 42)

Lilla Hyttnäs reached public success in Key’s essays. Key made a close connection between the Larssons’ home and its meaning for the home as a critical site for social reform. Despite her bourgeois background, Key meant that the neo-renaissance style of the time was “meaningless,” containing too much “kitsch and knick-knacks,” and complained that the concepts of “beauty” and “taste” were only extended to the upper classes. (Key 1899, 6) As such, she wrote extensively of a revised meaning of beauty within the home, expanding the concept to reach everyday things, and often referencing Lilla Hyttnäs in the process. Lilla Hyttnäs was inexcessive and modest, yet contained everything that one could wish for in living a comfortable domestic life. To Key, this functionality only added to the home’s inherent beauty. She meant that it was possible to create a beautiful and comfortable environment through cheap and simple means and painted an alluring image of Lilla Hyttnäs as a representative of this. Because of Karin’s influence in the design and figuration of Lilla Hyttnäs, Key also turned to the average Swedish woman with an urging of doing the same. Through a refashioning of the meaning of “beauty,” as well as a critique of the social organization of Sweden at the time, Key managed to spread the idea of the home as a site for instantiating aesthetic reform; something she clearly had in mind when designing her own home, Strand.

Inspired by the art nouveau, her

travels in Italy, as well as her childhood home, Strand was planned and drawn

by Ellen Key herself after extensive research collected in one of her

“tankeböcker” (transl.: “thought books”) called Praktiska Ting för Stuga och

Trädgård (transl.: Practical Things for Cabin and Garden). Praktiska

Ting compiles over 100 pages of Key’s thoughts about the home; on one page

she has written out potential cities in which to settle down (Båstad, Arild,

Ängelholm, Ljungskile), on another there are sketches of a country house from her travels in Rome, and on another there is practical knowledge stating that linseed-oil is the

best glaze for wooden floors and that “bird houses should have their entrance

facing east.” (Key 1910, 8) The

notebook, versatile and humoristic at times, is filled with cut-outs of

country-houses from German architectural magazines, Key’s own designs of floor

plans and furniture, extensive studies on windows, gardens, and light, and

scribbles of philosophical invocations such as “Memento Vivere!” The

final version of Strand, realized between the years of 1910-1911 by Key’s

brother-in-law, the Gothenburg-based Yngve Rasmussen, (Ambjörnsson 2012, 456) carries many of Key’s noted ideas: one of her early floor plans being that “which

Yngve drew after,” the famous flower shelf that now sits in the Strand library being her own

design, and the reminder-to-live decorating one of the walls of the hallway. (Key 1910) As such,

Strand existed in its entirety even before it was built; first imagined in

Key’s own mind and then translated in text and visuals in Praktiska Ting. Although

Strand draws upon several sources of inspiration – and although Key has

explicitly stated that she modeled the exterior of the house after her

childhood mansion, Sundsholm (Key 1917) – the making and the design of Strand gives us an insight into Key’s own aesthetic

ideals. Strand looks nothing like Rasmussen’s older work, such as his own house

in Malevik, as well as Tomtehuset in Gothenburg, making it clear that

Strand is indubitably Key’s own articulation; Rasmussen himself claimed to

never have had a better client – Ellen Key knew exactly how she wanted her

home to be built. (Bendt 2002) Similarly, although the exterior of the house is modeled after Sundsholm,

there are apparent connections made to the Italian villa, an influence from

Key’s extensive travels in the country, ranging from 1903-1909. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 450-451) Although Key was often denoted as being illogical and having her head in the

clouds, the planning and execution of her own home shows just how rational,

analytical, and self-sufficient she could be.

Fig 6. Ellen Key’s drawings (floor plan, flower shelf, and window and light studies) in Praktiska Ting.

Fig 6. Ellen Key’s drawings (floor plan, flower shelf, and window and light studies) in Praktiska Ting.

Nestled amongst nature on an incline of the Omberg mountain, with one side facing Sweden’s second largest lake, Vättern, and the other being barely being visible due to the sloping terrain, Strand is hidden in plain sight. The exterior of the house is vernacular in many ways: its narrow and elongated rectangular form, patches of light yellow, and apparent symmetry being typical for the traditional 1700s Swedish mansion; the paned windows often associated with national romantic ideals. (Ingemark 1998, 80-81) The details of the house are seemingly derived from the art nouveau, with softly curved surfaces and stylized flowers, swans, and faces used as surface décor. In contrast, Key also incorporated her dreams of Italy into the design. In a letter to her author friend Amalia Fahlstedt, Key writes: “If I didn’t have friends and a conscious I would not return to Sweden but settle down in Italy – it’s like it was my motherland; everything is as tailor-made for me […] but the heart does not live solely of nature and art, and my conscious wants to do good and find a home. Stupid conscious!” (Ambjörnsson 2012, 451) As a result of her longings, Key modeled the sun pavilion by the shore of Vättern after an antique temple which she seen in Sicily. Similarly, the focus on light and extensive studies on windows conducted on visits to Key’s friend Axel Munthe’s Villa San Michele in Rome, come together in Strand. The open floor plan and the clear division of service and entertainment areas in Strand derive from the Arts and Crafts movement but are also evocative of the buildings of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, drawn around the same time. (Ingemark 1998, 81) As noted by art historian Alice Friedman, Mamah Bouton Borthwick, Wright’s partner, was devoted to Ellen Key as an “ally and spiritual guide” and was one of the first visitors at Strand, her guest book signature dating to June 9, 1910; a sign that Key and Wright, despite never having met, were connected in thought. (Friedman 2002, 140)

The inside of Strand is timeless; a

mixture of old and new characterized by light and simplicity. The dining room

and the library combine to create a large, bright, living room with windows

facing three-ways. The walls are a matte light green, following Key’s own

writings of wallpaper featured in Beauty for All, stating to “be weary

of the dark wallpapers, with meaningless decorations” and that the expensive solid-colored wallpapers could be easily acquired by

buying cheap wallpapers but making the reverse solid side – rather than the

patterned one – visible. (Key 1899, 5-6) The curtains are sparsely woven in bright orange in which light can inevitably

peek through, something that was highly unusual in the dark neo-renaissance

homes at the time, where curtains were dark and heavy to shut out all unwanted

daylight. During

dark evenings, the fireplace in the dining room would be lit, an important part

within the home; Key believed that everyone that could afford it “should allow

their children to grow up with the joy of the fireplace.” (Key 1899, 40-41) The furniture is modest, a selection of simple wooden chairs, family heirlooms,

and Key’s own unpretentious designs (such as her famous flower shelf.) In the

library is a desk that Key was given as a 12-year old, the couch and armchairs

are inherited from her grandparents in Björnö, and most of the artwork are gifts from some of Key’s many artist friends: Prins

Eugen, Carl Larsson, Richard Berg, and Anders Zorn. (Forsström 1962, 21) The mixture of styles gives the room an informal and homey feel, corresponding

to her writings in Beauty for All. The bedroom is similarly modest,

painted in a bright yellow to evoke the feeling of being woken up by sunlight, with a small wooden-frame bed and family portraits hung on the wall. In our

age, Swedish design showcases itself first and foremost through the

home-furnishing company of IKEA, which is often associated with lofty, light

interiors, and simplistic wooden furniture. Founded in 1943, many of IKEA’s

core values can be traced back to Ellen Key and her Strand: the prominent use

of wood, the affordability, and the homey informality. Even the marketing

strategies of IKEA – aiming to sell by presenting their products nestled

in personal and intimate scenes of private life – trace back to Beauty

for All, and Key’s depiction of Lilla Hyttnäs. IKEA, much like the interior

of Strand, prides itself in being democratic, egalitarian, and affordable to

most. (IKEA 2020) Similarly, in discussions of the Scandinavian ideal of hygge, a buzzword

in recent years, the fireplace is often cited as an inherent piece in making a

place feel hyggelig. (Linnet 2011, 34) As such, Strand relates to several core values in Swedish design still today,

making it both timeless, as well as a prime case study for the origins of

Swedish design as we know it today.

Fig. 9. Ellen Key in the library of Strand To the right: the desk she received as a 12-year old; to the left is her self-designed flower shelf.

Sundbeck, Calla Helena. Ellen Key vid skrivbord på Strand. 1924. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021016297839/ellen-key-vid-skrivbord-pa-strand.

Fig. 9. Ellen Key in the library of Strand To the right: the desk she received as a 12-year old; to the left is her self-designed flower shelf.

Sundbeck, Calla Helena. Ellen Key vid skrivbord på Strand. 1924. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021016297839/ellen-key-vid-skrivbord-pa-strand.

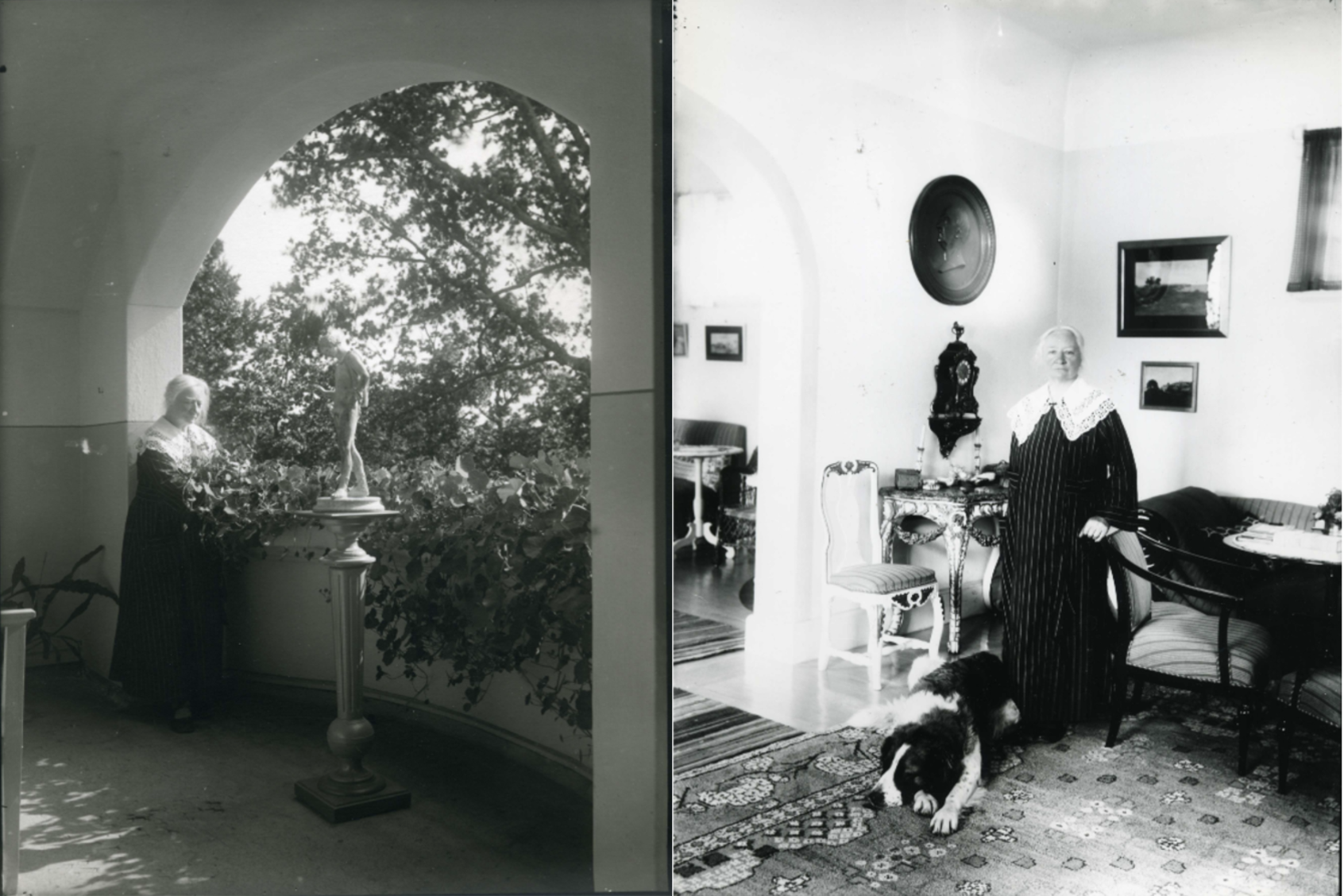

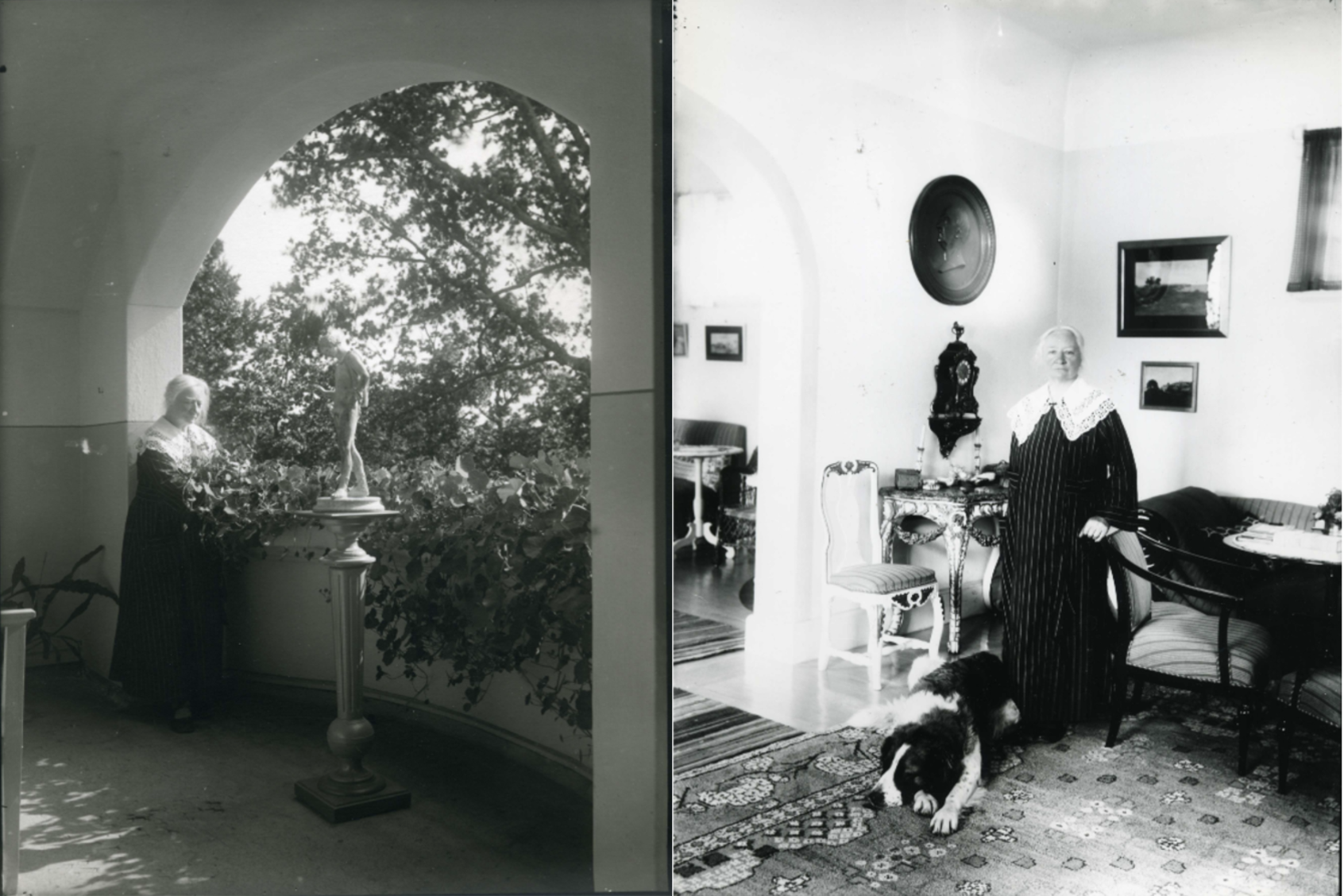

“Hemmets helgd” (“Home’s holiness”) was a mantra for Ellen Key. (Wittrock 1953, 402) Settling down alone but being deeply infatuated with Urban von Feilitzen – who refused to leave his family and elope with Key – she often felt lonely. “I would give everything, my books, my Strand, everything, everything that has been rich in my life, to get to have walked here with a little child in my hand, a child that was my own,” she wrote in her letters to Sigrid Gillner, and to the death of her St. Bernard, Gull, in 1919, she wrote: “I am met with yet another grave. The friend, that rests there, was as people say ‘just’ a dog. But he was the only thing of all, during a long time of living, that was completely and solely my own.” (Dahlgren 2012, 52-53) For Key, Strand became a sanctuary. Growing up in a Christian household, Key studied the bible extensively and wrote on and off about God before she abandoned her religion for secular philosophy. Inspired by philosopher Baruch Spinoza, Key rejected God as an individual entity and believed, much like Spinoza, that God was “not the creator of the world, but that the world is part of God.” (Carlisle 2011) As such, Key – also inspired by the anti-humanism of Friedrich Nietzsche – attributed a religious dimension to nature. In one of her thought books from the 1870s writes: “in every gust of wind I breathe, I feel God’s presence” and that “all of nature is one, whose parts (without changing the whole) are infinitely different.” (Ambjörnsson 2012, 474) With God no longer viewed as a singular entity, Key’s conception of life was found in the optimistic and all-encompassing future. As such, she never articulated her own life philosophy in words, but focused rather on the aesthetic of living a good life. Key believed that beauty had the power to turn people good by putting them in harmony, a philosophy that inescapably found its way into Strand; the house even having been called Key’s “spiritual testament” by her friend and frequent visitor, Alice Trolle. (Wittrock 1953, 109) The carefully designed balcony, which was called “Solbadet,” (transl.: “the sun bath”) was, according to Key herself, Strand’s “most beautiful space, where the bronze copy of Lyssnaren […] with his raised finger urges obedience to the spirit of listening, in the glow of the sun, the moon, or the stars.” (Key 1917) Surrounded by nature – the crowns of oaks and the glimmer of Vättern – Solbadet sought refuge in nature to become Key’s dedicated place of meditation and introspection. The idea of harmonious beauty was the foundation of Beauty for All, and something that Key also related to Strand as a pilgrimage site. In “Något om vila och om ett vilohem,” she writes: “In one of my oaks grows a small roan, the ancient magical charm. If I am ever tempted to use it, it will be for all those who in the future will walk on Strand, to conjure the state of mind without which Strand cannot provide them anything. I mean the inner stillness, which will make them enjoy the outer peace; the gift of devilishly embracing the beauty of nature; the desire to listen to the soul of the bygone era – the soul that lives in the memories of the countryside – and to the words of great spirits, the ones they will find in the bookcases of Strand. If they own this state of mind, they will find rest in Strand, the one I dream of, the dream, that made all hardships easy.” (Key 1917)

By treating Strand as a case study for many of Ellen Key’s ideas, we can get a better sense of who this enigmatic woman was. By using Strand as a place of experimentation, Key manifested her own beliefs of Beauty for All and exhibited them to the public. Her 1899 collection of essays was so influential that it became the basis of Gregor Paulsson and the Swedish Handicraft Association’s 1919 manifesto “Vackrare Vardagsvara,” (transl.: “More Beautiful Everyday Things”). With the Swedish Handicraft Association being tasked to promote Swedish design nationally and internationally, Ellen Key’s influence can be clearly seen in what came to be the foundational principles of Swedish design. The design of Strand itself, vernacular in exterior and humble in interior, bears the fruit of Ellen Key’s core beliefs and reflects onto her own persona. Hidden in plain sight, it relates closely to her beliefs of spirituality, domesticity, and altruism. Despite the soft and modest forms of Strand, however, Ellen Key was ferocious and radical, especially as a writer. Her ideas, not only on domesticity and design, but also on children’s education, love and marriage, and feminism live on, even today, proving once and for all that Ellen Key was a force to be reckoned with – and one not to be forgotten.

Ambjörnsson, Ronny. Ellen Key: En Europeisk Intellektuell. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2012.

Bendt, Ingela. Ett Hem för Själen: Ellen Keys Strand. Stockholm: Blue Publishing, 2016.

Bendt, Ingela. “Nytt ljus över Strand.” Populär Historia, July 3, 2002.

Carlisle, Claire. “Spinoza, part 1: Philosophy as a way of life.” The Guardian, February 7, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2011/feb/07/spinoza-philosophy-god-world.

Forsström, Axel. Infromationsbroschyr om Ellen Key. Stockholm: Ellen Key Stiftelse Strand, 1962.

Friedman, Alice. “Frank Lloyd Wright and Feminism: Mamah Borthwick’s Letters to Ellen Key.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 61, no. 2 (June 2002): 140–151.

Hellström Sveningson, Lis. Ellen Key Mitt I Världen: Från Strand till strand till strand. Gothenburg: Folkuniversitets Akademiska Press, 2011.

IKEA, “Democratic Design.” Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/this-is-ikea/democratic-design-en-gb/.

Ingemark, Anna. “Det privata hemmet som offentlig scen: Ellen Keys Strand & Verner von Heidenstams Övralid.” RIG: Kulturhistorisk Tidsskrift 81, no.2 (1998): 76–87.

Key, Ellen. “Något om Vila och ett Vilohem,” Julfacklan4 (December 1917), via “Strand.” Ellen Key Stiftelse Strand. Accessed May 13, 2020, https://www.ellenkey.se/strand/.

Key, Ellen. Praktiska Ting för Stuga och Trädgård, 1910. Digitalized by the National Library of Sweden in 2015. https://arken.kb.se/SE-S-HS-L41-3-24;isad?sf_culture=sv.

Key, Ellen. Skönhet för Alla: Fyra Uppsatser. Uppsala: Verdandis Småskrifter, 1899.

Linnet, Jeppe Trolle. “Money Can’t Buy me Hygge: Danish Middle-Class Consumption, Egalitarianism, and the Sanctity of Inner Space.” Social Analysis 55, no. 2 (June 2011): 21–44.

Söderholm, Carolina. Svenska Formgivare. Lund: Historiska Media, 2005.

Wittrock, Ulf. Ellen Keys Väg från Kristendom till Livstro. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, 1953.

Fig. 1. Ellen Key, middle, portrayed reading to her friends.

Pauli, Hanna. Vänner. Oil on Canvas. 1907. Digitalt Museum.

Accessed May 15, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021046508446/vanner.

Pauli, Hanna. Vänner. Oil on Canvas. 1907. Digitalt Museum.

Accessed May 15, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021046508446/vanner.

Whereas Ellen Key grew up with a right-wing politician as her father, she eventually started sympathizing with the rising movement of social democracy that developed in Sweden during the late 1880s. (Hellström Sveningson 2011, 44-45) The social democratic ideals of egalitarianism became central to Key’s work, and in 1883, Key joined the left liberalist student association Verdandi, with many of Sweden’s cultural elite, such as Gustaf af Geijerstam, Mauritz Hellberg, and Hjalmar Branting, already being members. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 172) Verdandi advocated for freedom of speech and published Verdandis Småskrifter (transl.: Verdandi’s Journals) in which Ellen Key reached the most success as a writer. In 1899, Verdandis Småskrifter published Key’s essays on beauty within the home in a four-series collection called Skönhet för Alla, (transl.: Beauty for All), which compiled into Key’s aesthetic manifesto. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 436) Inspired by John Ruskin and William Morris’ Arts and Crafts movement in the United Kingdom, Beauty for All directly opposed the low-quality mass-produced goods of industrialization, advocating instead for a return of romanticism, traditional craftsmanship, and folk-style decoration. In Sweden, the influences of the Arts and Crafts movement could be most prominently seen in Lilla Hyttnäs, the Sundborn home of artists Carl and Karin Larsson, which Key praised in her essay as a home that had used “simple means [to reach] the most homely and personal impression.” (Key 1889, 14) Lilla Hyttnäs was an artistic statement: an egalitarian aesthetic in which the handmade coexisted comfortably within the home. Designed entirely by the two Larsson’s, the home was a bold opposition to the dominant design influences in Sweden at the time. It opposed both the decorative neo-renaissance by being characterized by light, simple, and lofty interiors, as well as the industrial mass-production, by being completely handmade: Carl designed the furniture, and Karin wove and knitted various tapestries and textiles. The home was later captured in Carl Larsson’s 1899 book, A Home, which contained 24 watercolor paintings of intimate scenes from the Larsson’s everyday life; the book revolutionized the way Swedes conceived home life and home decoration by introducing the simple concept of domestic informality and comfort. (Söderholm 2005, 42)

Fig. 2. Scenes from Carl Larssons A Home.

Larsson, Carl. “Lathörnet.” Watercolor, 1897. In Ett Hem. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1899.

Larsson, Carl. “Lathörnet.” Watercolor, 1897. In Ett Hem. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1899.

Lilla Hyttnäs reached public success in Key’s essays. Key made a close connection between the Larssons’ home and its meaning for the home as a critical site for social reform. Despite her bourgeois background, Key meant that the neo-renaissance style of the time was “meaningless,” containing too much “kitsch and knick-knacks,” and complained that the concepts of “beauty” and “taste” were only extended to the upper classes. (Key 1899, 6) As such, she wrote extensively of a revised meaning of beauty within the home, expanding the concept to reach everyday things, and often referencing Lilla Hyttnäs in the process. Lilla Hyttnäs was inexcessive and modest, yet contained everything that one could wish for in living a comfortable domestic life. To Key, this functionality only added to the home’s inherent beauty. She meant that it was possible to create a beautiful and comfortable environment through cheap and simple means and painted an alluring image of Lilla Hyttnäs as a representative of this. Because of Karin’s influence in the design and figuration of Lilla Hyttnäs, Key also turned to the average Swedish woman with an urging of doing the same. Through a refashioning of the meaning of “beauty,” as well as a critique of the social organization of Sweden at the time, Key managed to spread the idea of the home as a site for instantiating aesthetic reform; something she clearly had in mind when designing her own home, Strand.

|

Fig 6. Ellen Key’s drawings (floor plan, flower shelf, and window and light studies) in Praktiska Ting.

Fig 6. Ellen Key’s drawings (floor plan, flower shelf, and window and light studies) in Praktiska Ting.Nestled amongst nature on an incline of the Omberg mountain, with one side facing Sweden’s second largest lake, Vättern, and the other being barely being visible due to the sloping terrain, Strand is hidden in plain sight. The exterior of the house is vernacular in many ways: its narrow and elongated rectangular form, patches of light yellow, and apparent symmetry being typical for the traditional 1700s Swedish mansion; the paned windows often associated with national romantic ideals. (Ingemark 1998, 80-81) The details of the house are seemingly derived from the art nouveau, with softly curved surfaces and stylized flowers, swans, and faces used as surface décor. In contrast, Key also incorporated her dreams of Italy into the design. In a letter to her author friend Amalia Fahlstedt, Key writes: “If I didn’t have friends and a conscious I would not return to Sweden but settle down in Italy – it’s like it was my motherland; everything is as tailor-made for me […] but the heart does not live solely of nature and art, and my conscious wants to do good and find a home. Stupid conscious!” (Ambjörnsson 2012, 451) As a result of her longings, Key modeled the sun pavilion by the shore of Vättern after an antique temple which she seen in Sicily. Similarly, the focus on light and extensive studies on windows conducted on visits to Key’s friend Axel Munthe’s Villa San Michele in Rome, come together in Strand. The open floor plan and the clear division of service and entertainment areas in Strand derive from the Arts and Crafts movement but are also evocative of the buildings of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, drawn around the same time. (Ingemark 1998, 81) As noted by art historian Alice Friedman, Mamah Bouton Borthwick, Wright’s partner, was devoted to Ellen Key as an “ally and spiritual guide” and was one of the first visitors at Strand, her guest book signature dating to June 9, 1910; a sign that Key and Wright, despite never having met, were connected in thought. (Friedman 2002, 140)

|

Fig. 9. Ellen Key in the library of Strand To the right: the desk she received as a 12-year old; to the left is her self-designed flower shelf.

Sundbeck, Calla Helena. Ellen Key vid skrivbord på Strand. 1924. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021016297839/ellen-key-vid-skrivbord-pa-strand.

Fig. 9. Ellen Key in the library of Strand To the right: the desk she received as a 12-year old; to the left is her self-designed flower shelf.

Sundbeck, Calla Helena. Ellen Key vid skrivbord på Strand. 1924. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://digitaltmuseum.se/021016297839/ellen-key-vid-skrivbord-pa-strand.Ellen Key lived in Strand until her

death in 1926, after which Strand was turned into a resting home for the

working women of Sweden – something Key decided upon already before Strand was

fully realized. (Forsström 1962, 21) Strand

was designed to eventually be public, and was, as we already know, carefully

planned and curated. Already before Key’s own death, there was a steady stream

of visitors: both devoted disciples of hers that saw the home as a site of

pilgrimage, as well as friends and colleagues of Sweden’s cultural elite at the

time. In “Några tankar om vila och ett vilohem,” published in Julfacklan 1912,

Key wrote, about the build of Strand: “I knew that the great joy derived from

this own home would be, not that I could own it for the couple of decades I

have left to live, but that it, already while I was alive – and after

my death – would prepare a time of rest from life’s miseries or the

sorrows of those exhausted.” (Key 1917) Thus, the dynamic relationship between the public and the private must inevitably

have been carefully considered during Key’s planning process. This may perhaps

be best seen in the large living room, which came to replace the 17th

century salon, and in which Ellen Key is often depicted reading to her friends.

Key often mentioned that “the books built [Strand],” which the library proudly displays. (Ambjörnsson 2012, 364) Placed in a specially customized bookshelf,

the living-room is overflowing with worn and well-read books, ranging from

those of dense philosophy to those of children’s stories. (Ingemark 1998, 84) The books as a backdrop to Key’s public gatherings and their intellectual

discourse are fitting in revealing her own ideals and persona; she started

reading as a four-year-old and never stopped. Even today, Strand is furnished the same way as it was when Ellen Key moved in,

and thus in the same way as it is depicted in the sketches of Praktiska

Ting. We can thus speculate in Strand as a performative act. With the Ellen

Key foundation still operational and providing summer residency to three women

each year, we can get a somewhat clear idea of Ellen Key’s values and lifestyle

by visiting and living within the home. Above all, however, Strand can perhaps be

seen as performative, providing insight to the persona that Key wanted to

be portrayed as, her ideals carefully curated within the walls of her home.

Fig. 11. Ellen Key in solbadet and with her dog, Gull.

Sundbeck, Calla Helena. Ellen Key med hunden Gull på Strand. 1924. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 15, 2020.

Sundbeck, Calla Helena. Ellen Key med hunden Gull på Strand. 1924. Digitalt Museum. Accessed May 15, 2020.

“Hemmets helgd” (“Home’s holiness”) was a mantra for Ellen Key. (Wittrock 1953, 402) Settling down alone but being deeply infatuated with Urban von Feilitzen – who refused to leave his family and elope with Key – she often felt lonely. “I would give everything, my books, my Strand, everything, everything that has been rich in my life, to get to have walked here with a little child in my hand, a child that was my own,” she wrote in her letters to Sigrid Gillner, and to the death of her St. Bernard, Gull, in 1919, she wrote: “I am met with yet another grave. The friend, that rests there, was as people say ‘just’ a dog. But he was the only thing of all, during a long time of living, that was completely and solely my own.” (Dahlgren 2012, 52-53) For Key, Strand became a sanctuary. Growing up in a Christian household, Key studied the bible extensively and wrote on and off about God before she abandoned her religion for secular philosophy. Inspired by philosopher Baruch Spinoza, Key rejected God as an individual entity and believed, much like Spinoza, that God was “not the creator of the world, but that the world is part of God.” (Carlisle 2011) As such, Key – also inspired by the anti-humanism of Friedrich Nietzsche – attributed a religious dimension to nature. In one of her thought books from the 1870s writes: “in every gust of wind I breathe, I feel God’s presence” and that “all of nature is one, whose parts (without changing the whole) are infinitely different.” (Ambjörnsson 2012, 474) With God no longer viewed as a singular entity, Key’s conception of life was found in the optimistic and all-encompassing future. As such, she never articulated her own life philosophy in words, but focused rather on the aesthetic of living a good life. Key believed that beauty had the power to turn people good by putting them in harmony, a philosophy that inescapably found its way into Strand; the house even having been called Key’s “spiritual testament” by her friend and frequent visitor, Alice Trolle. (Wittrock 1953, 109) The carefully designed balcony, which was called “Solbadet,” (transl.: “the sun bath”) was, according to Key herself, Strand’s “most beautiful space, where the bronze copy of Lyssnaren […] with his raised finger urges obedience to the spirit of listening, in the glow of the sun, the moon, or the stars.” (Key 1917) Surrounded by nature – the crowns of oaks and the glimmer of Vättern – Solbadet sought refuge in nature to become Key’s dedicated place of meditation and introspection. The idea of harmonious beauty was the foundation of Beauty for All, and something that Key also related to Strand as a pilgrimage site. In “Något om vila och om ett vilohem,” she writes: “In one of my oaks grows a small roan, the ancient magical charm. If I am ever tempted to use it, it will be for all those who in the future will walk on Strand, to conjure the state of mind without which Strand cannot provide them anything. I mean the inner stillness, which will make them enjoy the outer peace; the gift of devilishly embracing the beauty of nature; the desire to listen to the soul of the bygone era – the soul that lives in the memories of the countryside – and to the words of great spirits, the ones they will find in the bookcases of Strand. If they own this state of mind, they will find rest in Strand, the one I dream of, the dream, that made all hardships easy.” (Key 1917)

By treating Strand as a case study for many of Ellen Key’s ideas, we can get a better sense of who this enigmatic woman was. By using Strand as a place of experimentation, Key manifested her own beliefs of Beauty for All and exhibited them to the public. Her 1899 collection of essays was so influential that it became the basis of Gregor Paulsson and the Swedish Handicraft Association’s 1919 manifesto “Vackrare Vardagsvara,” (transl.: “More Beautiful Everyday Things”). With the Swedish Handicraft Association being tasked to promote Swedish design nationally and internationally, Ellen Key’s influence can be clearly seen in what came to be the foundational principles of Swedish design. The design of Strand itself, vernacular in exterior and humble in interior, bears the fruit of Ellen Key’s core beliefs and reflects onto her own persona. Hidden in plain sight, it relates closely to her beliefs of spirituality, domesticity, and altruism. Despite the soft and modest forms of Strand, however, Ellen Key was ferocious and radical, especially as a writer. Her ideas, not only on domesticity and design, but also on children’s education, love and marriage, and feminism live on, even today, proving once and for all that Ellen Key was a force to be reckoned with – and one not to be forgotten.

References

Ambjörnsson, Ronny. Ellen Key: En Europeisk Intellektuell. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2012.

Bendt, Ingela. Ett Hem för Själen: Ellen Keys Strand. Stockholm: Blue Publishing, 2016.

Bendt, Ingela. “Nytt ljus över Strand.” Populär Historia, July 3, 2002.

Carlisle, Claire. “Spinoza, part 1: Philosophy as a way of life.” The Guardian, February 7, 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/belief/2011/feb/07/spinoza-philosophy-god-world.

Forsström, Axel. Infromationsbroschyr om Ellen Key. Stockholm: Ellen Key Stiftelse Strand, 1962.

Friedman, Alice. “Frank Lloyd Wright and Feminism: Mamah Borthwick’s Letters to Ellen Key.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 61, no. 2 (June 2002): 140–151.

Hellström Sveningson, Lis. Ellen Key Mitt I Världen: Från Strand till strand till strand. Gothenburg: Folkuniversitets Akademiska Press, 2011.

IKEA, “Democratic Design.” Accessed May 14, 2020. https://www.ikea.com/gb/en/this-is-ikea/democratic-design-en-gb/.

Ingemark, Anna. “Det privata hemmet som offentlig scen: Ellen Keys Strand & Verner von Heidenstams Övralid.” RIG: Kulturhistorisk Tidsskrift 81, no.2 (1998): 76–87.

Key, Ellen. “Något om Vila och ett Vilohem,” Julfacklan4 (December 1917), via “Strand.” Ellen Key Stiftelse Strand. Accessed May 13, 2020, https://www.ellenkey.se/strand/.

Key, Ellen. Praktiska Ting för Stuga och Trädgård, 1910. Digitalized by the National Library of Sweden in 2015. https://arken.kb.se/SE-S-HS-L41-3-24;isad?sf_culture=sv.

Key, Ellen. Skönhet för Alla: Fyra Uppsatser. Uppsala: Verdandis Småskrifter, 1899.

Linnet, Jeppe Trolle. “Money Can’t Buy me Hygge: Danish Middle-Class Consumption, Egalitarianism, and the Sanctity of Inner Space.” Social Analysis 55, no. 2 (June 2011): 21–44.

Söderholm, Carolina. Svenska Formgivare. Lund: Historiska Media, 2005.

Wittrock, Ulf. Ellen Keys Väg från Kristendom till Livstro. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur, 1953.

Fig. 7. Strand, a mixture between the Swedish mansion and the Italian villa. Ellen Key Strand Stiftelse, Strand.

Fig. 7. Strand, a mixture between the Swedish mansion and the Italian villa. Ellen Key Strand Stiftelse, Strand.  Fig. 8. Ellen Key and her Strand nestled amongst the nature of

Omberg.

Fig. 8. Ellen Key and her Strand nestled amongst the nature of

Omberg.